THE HISTORY OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE – PART I.

The History of AI. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a hot topic today, with programs like ChatGPT showing the world how powerful and capable it has become. However, AI is not a new concept invented in the 21st century. The idea of AI can be traced back to ancient mythology where tales of artificial beings that possessed human-like qualities were common.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a hot topic today, with programs like ChatGPT showing the world how powerful and capable it has become. However, AI is not a new concept invented in the 21st century. The idea of AI can be traced back to ancient mythology where tales of artificial beings that possessed human-like qualities were common.

Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence conference. From left to right: Oliver Selfridge, Nathaniel Rochester, Ray Solomonoff, Marvin Minsky, Trenchard More, John McCarthy, Claude Shannon. Credit: aiws.net

The idea of creating machines that could think like humans began to take shape in the mid-twentieth century, with the emergence of electronic computers. In the 1940s and 1950s, computers could not store commands, only execute them. They were also extremely expensive and only prestigious universities or big companies could afford them. During this time pioneers such as John von Neumann and Alan Turing made significant contributions to the field of AI, laying the groundwork for modern programming.

In 1956, the concept of AI was initialized at a historic conference „Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence” (DSRPAI) hosted by John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky. “Logic Theorist”, a program designed to mimic human problem-solving skills created by Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon was introduced here. The program is considered to be the first AI program in the world. McCarthy proposed a two-month project that brought together top researchers to explore artificial intelligence. Unfortunately, the conference didn’t bring the success McCarthy wished for. However, the significance of this event cannot be undermined. AI gained its name, its mission, and its first success.

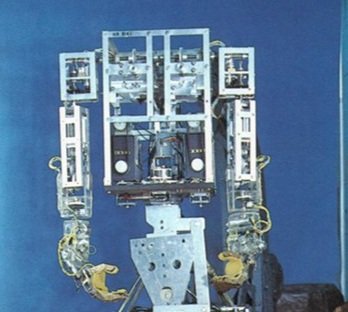

In the 1960s computers became faster, cheaper, and more accessible and they could store more information. This period was significant progress in the field of AI, with the development of programs such as the “General Problem Solver”, which could solve a wide range of problems by breaking them down into smaller parts. Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA also showed promise to be the first chatbot in 1966. In Japan, Waseda University introduced WABOT-1 in 1972, the first full-scale “intelligent” humanoid robot. Its limb control system allowed it to walk, grip and transport objects with its hands. It could also measure distances, and directions and communicate with a person in Japanese. These successes convinced governments to fund AI research at several universities and research institutions.

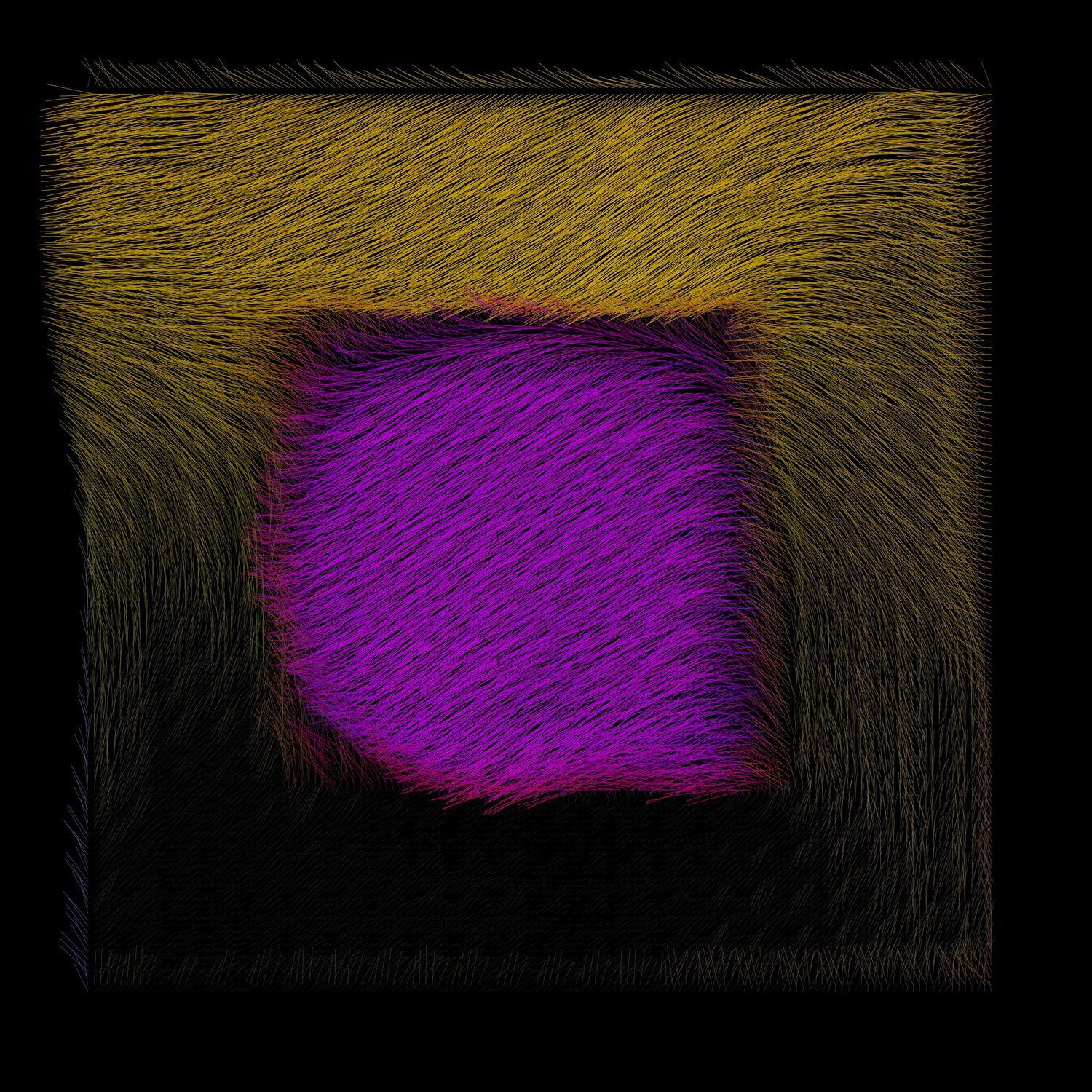

Alongside AI, computer-generated art has also taken its first steps. The genre dates back to the 1960s when artists like Frieder Nake, Georg Nees, Michael Noll, and Vera Molnár began to use computers to create geometric and abstract artworks. These artists developed algorithms and mathematical formulas to create simple patterns and shapes. While these artists were not necessarily working with what we would now consider AI, they were still important in establishing the field of computer-generated art and exploring computers as a tool for artistic expression.

In the 1970s, after the optimism, AI researchers encountered many obstacles and the promised results failed to materialize. The biggest obstacle was the lack of computer power. The computers could not store enough data or process it fast enough. AI became the subject of critique, and the researchers faced a crisis as funding was cut. The so-called “AI winter” lasted until the 1980s.

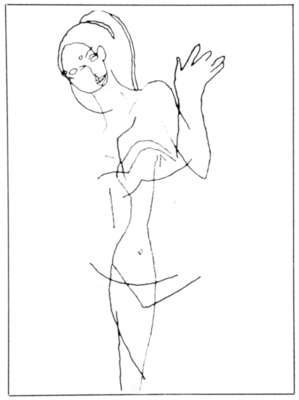

However, many researchers didn't give up on their hopes and continued to work in this field. A significant milestone in the history of AI-generated art is the development of AARON by Harold Cohen, which is considered to be the first AI art system. Cohen had been working on the project since the early 1970s at the University of California, San Diego, where he taught. AARON was designed to produce art autonomously, using a symbolic rule-based approach to generate images. In its initial form, it created simple black and white drawings that grew more complex over the years. At first, he used custom-built plotter devices, and sometimes he coloured these images by hand. In the 1980s, he managed to add more representational imagery such as plants, people, and interior scenes.

WABOT-1 (1970~1973) Credit: Humanoid Robotics Institute, Waseda University

In the 1980s, AI experienced a resurgence in popularity. The "Expert System," created by Edward Feigenbaum, was a major success as it mimicked the decision-making process of a human being, providing advice to users. The Japanese government funded the project as well as other AI tools with its “Fifth-Generation Computer Project”. Unfortunately, as had happened before, most of the ambitious goals were not met, and the second 'AI winter' began, with most of the funding being cut again.

In the 1990s and 2000s, many goals of artificial intelligence had been achieved. In 1997, Deep Blue became the first computer chess-playing system that beat a world chess champion, Garry Kasparov. The event was broadcast live on the internet and served as a huge step forward for AI. In the same year, speech recognition software was added to Windows. In 2002, for the first time, AI entered the home with Roomba, a vacuum cleaner. AI was also used in fields, such as mathematics, electrical engineering, economics, and operations research. It seemed that there was not a problem that AI could not sort out. During this period, computer storage became bigger, and the emergence of the internet provided access to large amounts of data. Cheaper and faster computers were able to successfully solve many problems of AI.

Garry Kasparov makes a move against the IBM Deep Blue. Credit: Stan Honda Getty Images

The advancements in AI technology took a significant leap forward in 2011 when IBM's Watson computer competed on the game show Jeopardy!. Watson was designed to process natural language questions and provide accurate responses, and it was able to defeat two of Jeopardy!'s most successful human competitors.

Another significant achievement was when Geoffrey Hinton at Google began to work on deep learning systems in the 2010s. Deep learning uses artificial neural networks to analyze and process data, learning from examples. Google quickly recognized the potential of deep learning and started investing in the technology. In 2015, they created AlphaGo, a computer program that was able to defeat the world champion in the game, Go. This was an important accomplishment, as Go has many possible board configurations, making it much more complex than chess.

Deep learning systems have given a huge boost to the development of image generation. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) were developed by Ian Goodfellow and colleagues in 2014. GANs work with two neural networks. A "generative" one is trained on a specific dataset (such as images of flowers or objects) until it can recognize them and generate a new image. And the "discriminator" system, has been trained to distinguish between real and generated images and evaluates the generator's first attempts. After a million times sending ideas back and forth, the generator AI produces better and better images. Since the introduction of GANs, many artists have made significant contributions to the field of AI-generated art using this technology, such as Mario Klingemann, and Robbie Barrat. The latter has used GANs to generate surreal and abstract portraits. The use of GANs in art has opened up new possibilities for artists to create unique works.

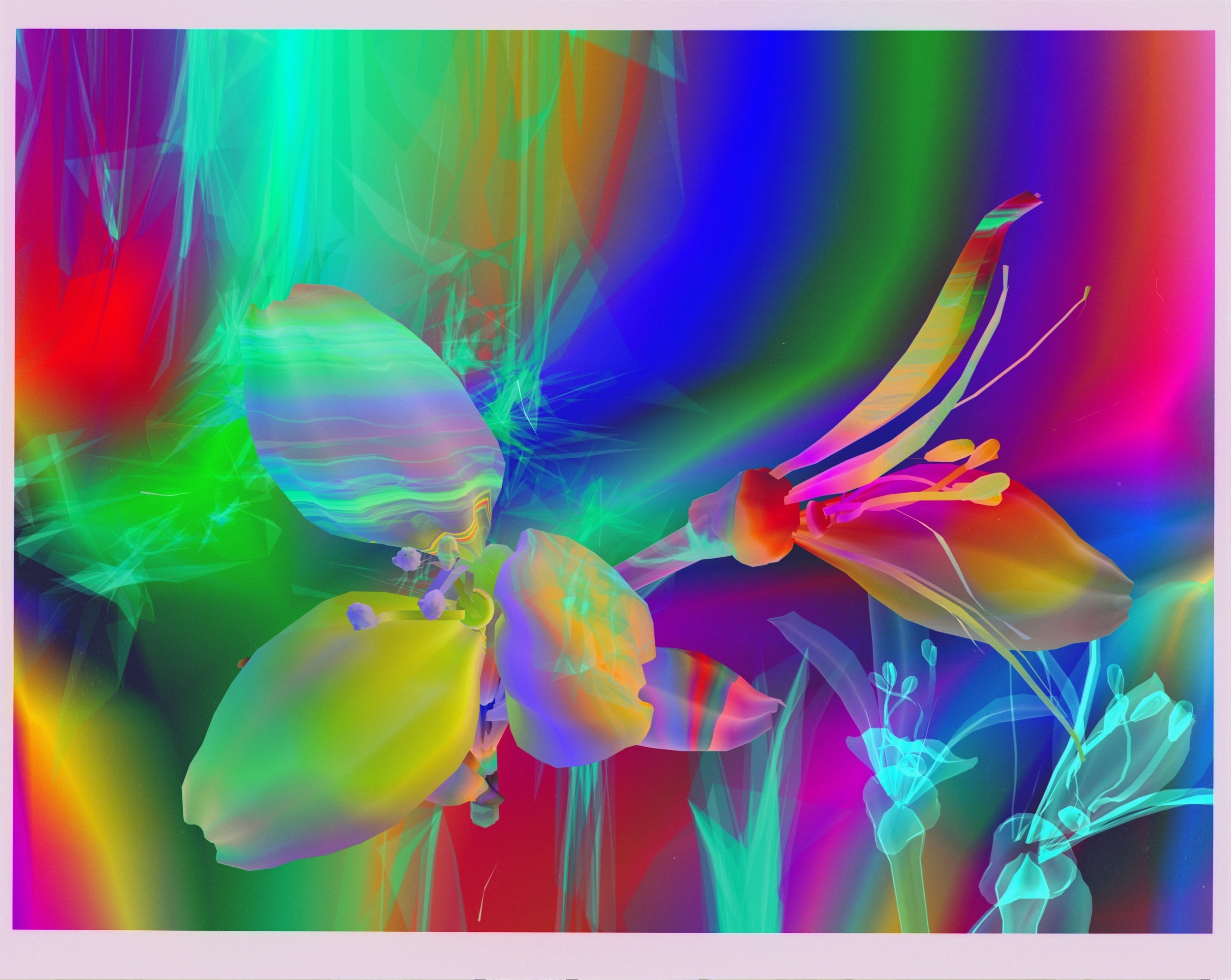

Another significant contribution to the field of image generation is DeepDream, which was developed by Alexander Mordvintsev at Google in 2015. DeepDream uses a convolutional neural network to find patterns in images, thus creating a dream-like, psychedelic appearance on them. In the following years, several companies released apps (like Artbreeder) that transform photos into the style of well-known paintings or generate images based on texts (such as DALL-E).

Not only in the art field, but in general, AI research and development has rapidly increased. Many other big tech companies, like Microsoft and Facebook, are investing in the field. In recent years, AI has entered into our everyday lives, from virtual assistants (Siri or Alexa) to personalized recommendations (on Netflix or Spotify). AI has also been used in healthcare to develop more accurate diagnoses, and in the finance industry to detect fraud and make better investment decisions. In the future, AI technologies will continue to influence the way we live, work and interact with the world around us.

In our next article, we’ll introduce the most recent achievements of AI, including ChatGTP, DALL-E 2, or Lumen5. Stay tuned!

Browse the works of some of our AI artists:

Panel talks at «Le monde non objectif» exhibition finissage

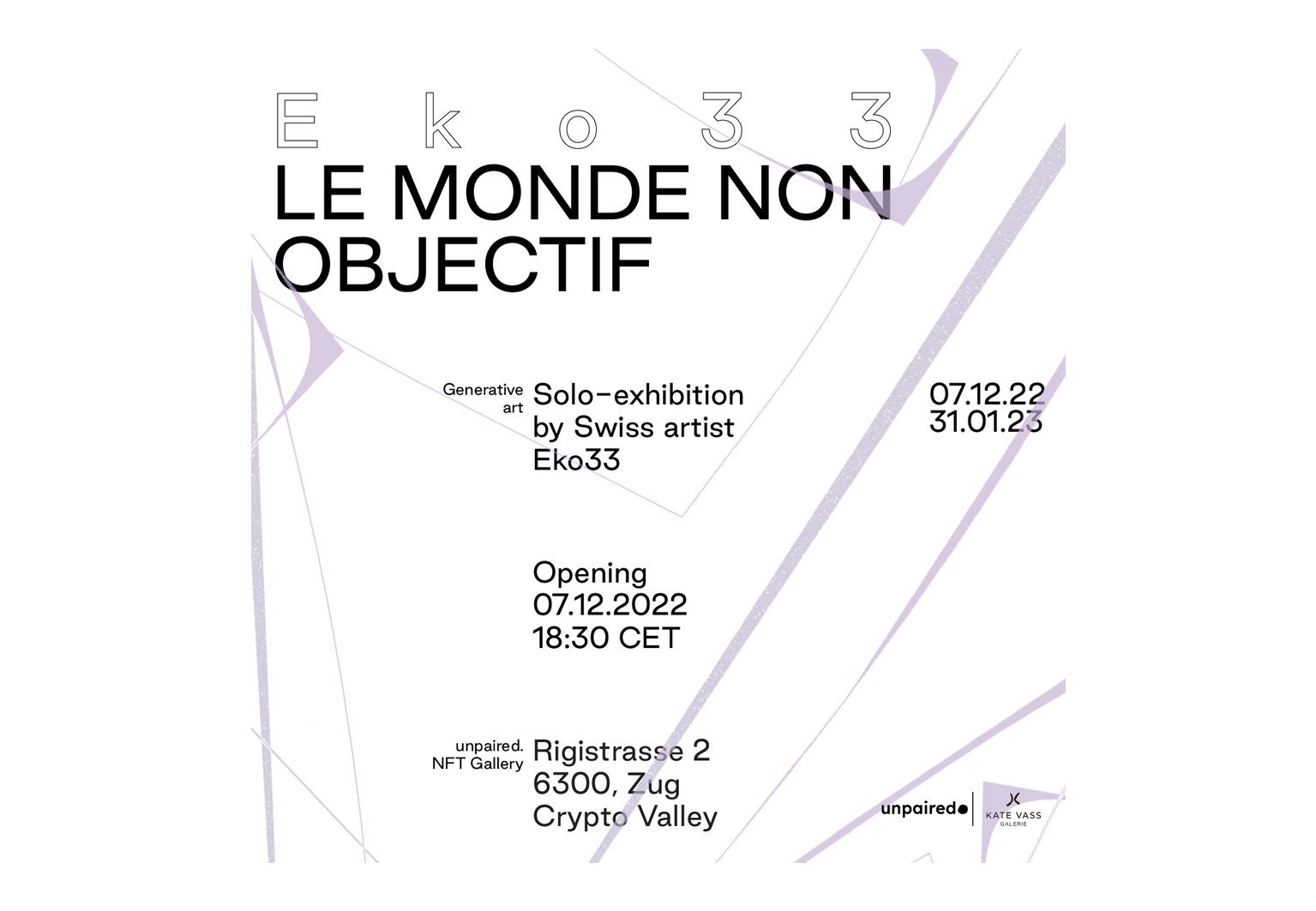

On 31/1, at the finissage of the solo show of Swiss generative artist Eko33 "Le monde non objectif", curated by Kate Vass Galerie at unpaired, we also hosted the panel about the history and the future of generative art. The conversation foregrounds key definitions to examine the history of the human & the machine relationship. The panel was meant to outline current tendencies and their relation to art history with decades of experimentation.

Our speakers: are Eko33, Johannes Gees, Lukas Amacher, and Georg Bak, chaired by Kate Vass.

Digital art did not develop in an art-historical vacuum; it has strong connections to previous art movements, including Dada, Fluxus and conceptual art. The importance of the above for digital art resides in their emphasis on formal instruction and their focus on concept, event, and audience participation, as opposed to unified material objects. The idea of rules being process for creating art has a clear connection with the algorithms that form the basis of all software and every computer operation: a procedure of formal instructions that accomplish a 'result' in a finite number of steps. Just as with Dadaist poetry, the basis of any form of computer art is instruction as a conceptual element. Art's notions of interaction and 'virtuality' were also explored early on by artists such as Marcel Duchamp & Laszlo Moholy Nagy in relation to objects & their optical effects. Duchamp's work, in particular, has been extremely influential in digital art: the shift from object to concept embodied in many of his works can be seen as a predecessor of the 'virtual object' as a structure in the process. Fluxus group performances and events in the 1960s were also often based on the execution of precise instructions.

The element of 'controlled randomness' that emerges in Dada, OULIPO, and the works of Duchamp & John Cage points to one of the basic principles and most common digital medium paradigms, the concept of random access as a basis for processing and assembling information. Computers were used for the creation of artworks as early as the 1960s. Michael A. Noll, a researcher at Bell Labs, created some of the earliest computer-generated images, e.g. Gaussian Quadratic (1963), which were shown at Howard Wise gallery in NY in 1965.

We invite you to browse the catalogue of the show here and follow up for more events:

#generativeart #curatedart #digitalart #historyofart

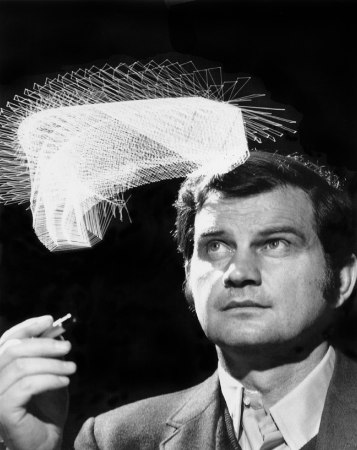

The Father of Computer Art: The Art of Charles Csuri

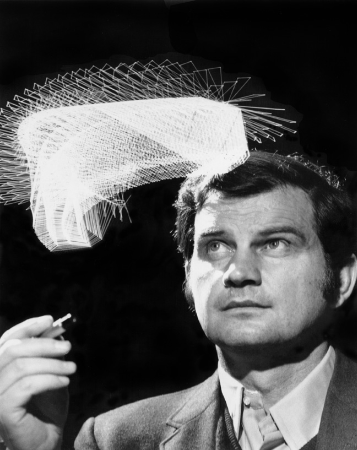

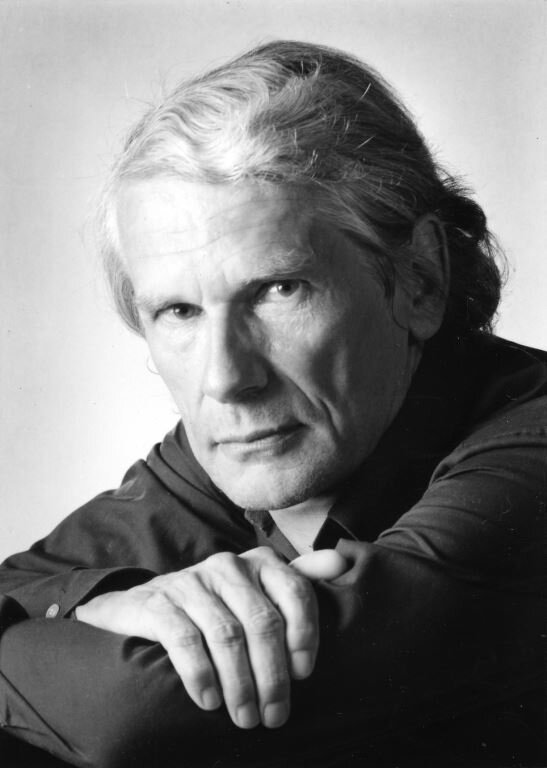

Charles Csuri, Image © the artist

Charles Csuri (1922-2022) is known as “The Father of Computer Art”. He was a professor, fine artist, and computer scientist who made significant contributions to the field of computer art. Through his research and artistic vision, Csuri developed software that created new artistic tools for 3D computer graphics, computer animation, gaming, and 3d printing.

Charles Csuri was born in 1922 in Grant Town, West Virginia, to immigrant parents from Hungary. He afforded college with a football scholarship in 1942 to The Ohio State University. After attaining The Bronze Star for heroism in WWII at “The Battle of The Bulge” he continued his education with the GI bill. Further, in 1943 the US Army sent him to the Newark College of Engineering, where he studied algebra, trigonometry, analytic geometry, calculus, physics, and chemistry, and received a degree in engineering. After the war, Csuri turned down an opportunity as an All American O.S.U. football player to join the NFL. Instead, he received his MFA in classical art education studying painting, drawing, and sculpture alongside his close friend Roy Lichtenstein in the 1940s. In 1947 Csuri became a professor teaching fine art while exhibiting his paintings in N.Y. During this time, he created traditional paintings, drawings, and sculptures but had a continuing dialogue with a friend and engineer at The Ohio State University in the early 1950s about working with the computer to create art. The problem seemed like science fiction till 1964 when he saw a raster image made using a computer. In the same year, he took a course on computer programming and created his first computer-generated picture in 1964 with an analogue computer and in 1965 an IBM 7094 with a drum plotter using FORTRAN programming language. In addition to teaching fine art, Csuri became a professor of Computer Information Science and created digital art with custom software in a Unix environment.

In 1968, Csuri sent shockwaves through the University by being the first artist to receive financial support from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Csuri used this funding to support computer scientists in a collaborative effort to develop the artist's tools he envisioned to create computer art. He implemented a three-part program: building up a library of data and programs that focused on creating new artistic tools for the generation and transformation of images, developing a graphic console, and establishing an educational program. With the grant, he proposed a formal organization, called the Computer Graphics Research Group (CGRG) at OSU in 1971, which he later renamed to Advanced Computer Center for the Arts and Design (ACCAD), in order to develop and experiment with the potential of the application of computer animation. NSF was so impressed with his work, that they supported his creative research for twenty years. The results of this research have been applied to a variety of fields, including flight simulators, computer-aided design, visualization of scientific phenomena, magnetic resonance imaging, education for the deaf, architecture, and special effects for television and films. In 1984, Csuri established the first computer animation company in the world, Cranston Csuri Productions, which produced animation for all three major U.S. television networks, the BBC, and commercial clients.

EARLY PERIOD (1963 - 1974)

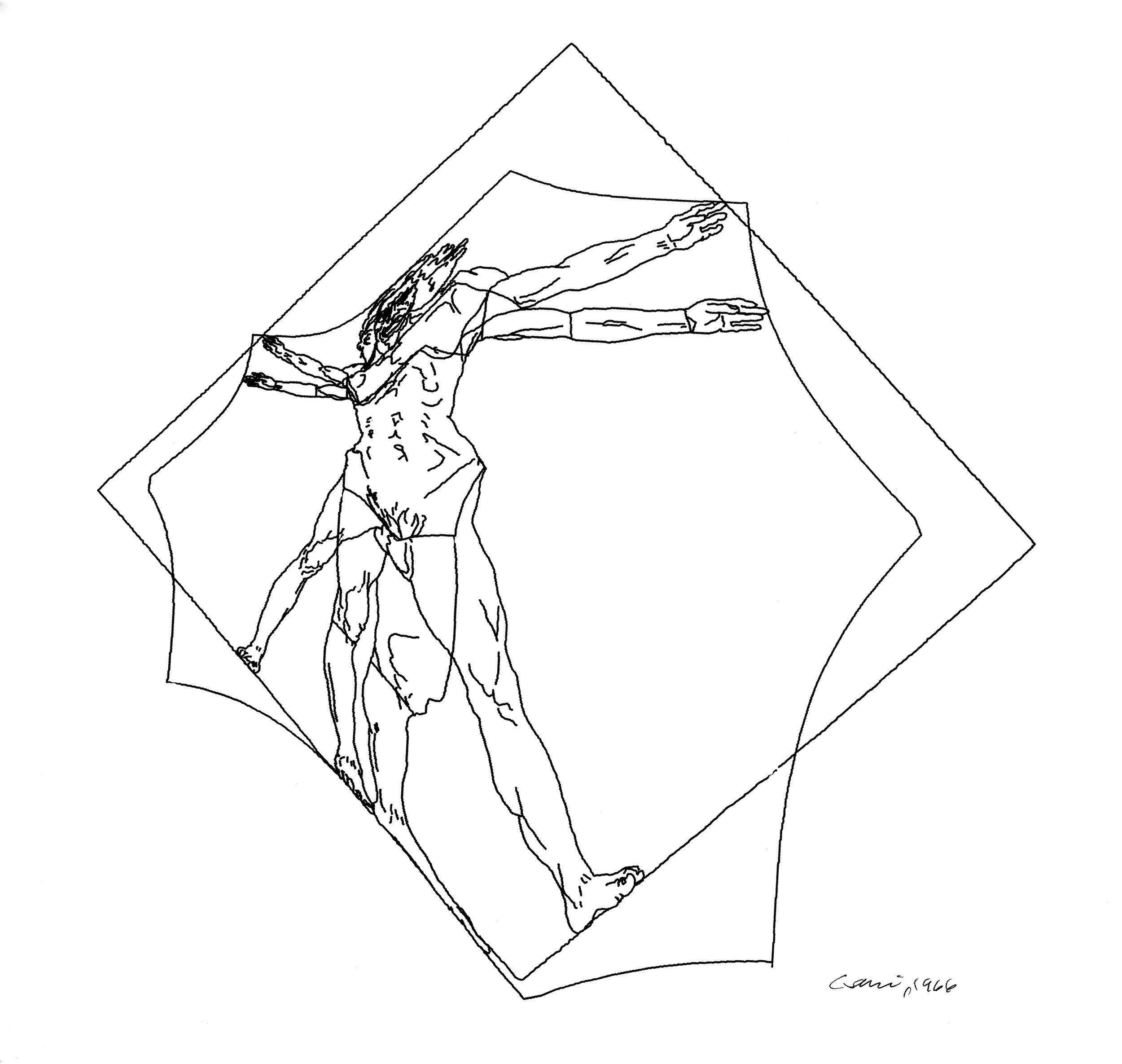

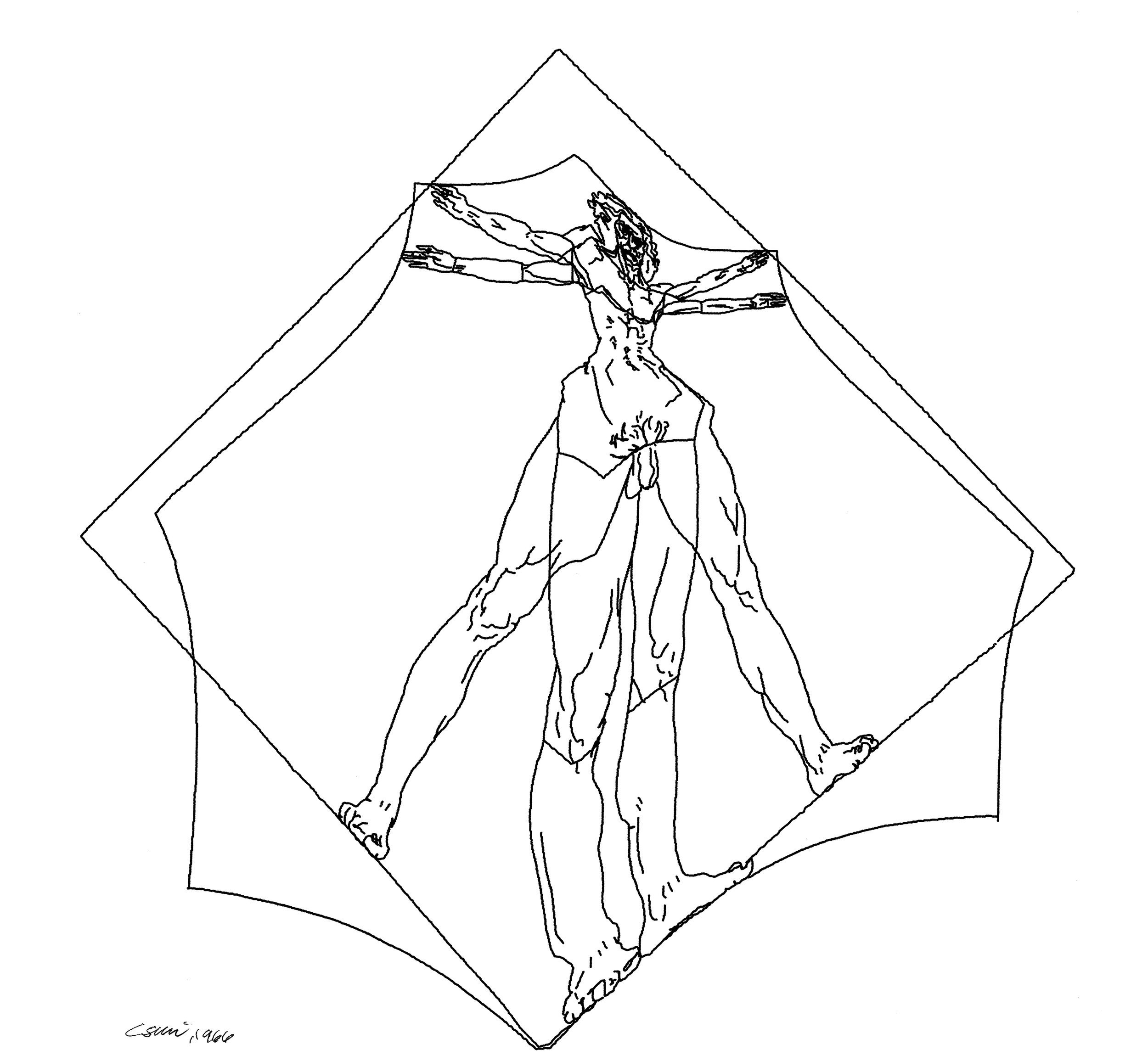

His early works, from mid-1963 to the 1970s are significant. His way of thinking about computer art, his creative process, and his intentions during this period helped shape his later art. Many of the themes, such as object transformation, hierarchical levels of control, and randomness were established in the early years. In the early days of his career, Csuri's art consisted of his drawings and sketches, which he made in order to mathematically transform them using analogue and digital technologies. In 1968 Csuri made an important discovery by creating a numeric milling machine sculpture as the brainchild for his pioneering development in the next phase of his career. In the early 1970’s he took this visionary idea further to develop 3D animation and real-time interactive art objects.

One of the best examples of his early period is the Hummingbird (1967), which is considered to be one of the earliest computer-animated films. To create the film, he generated over 30.000 images with 25+ different motion sequences using computer punch cards. The output was then drawn directly onto the film using a microfilm plotter. The resulting animation shows a hummingbird dissolving, recomposing, and floating along imaginary waves. The film received an award at the Fourth International Experimental Film Competition in Brussels, then MoMA in New York purchased it in 1967 for its permanent collection as one of the first computer animations.

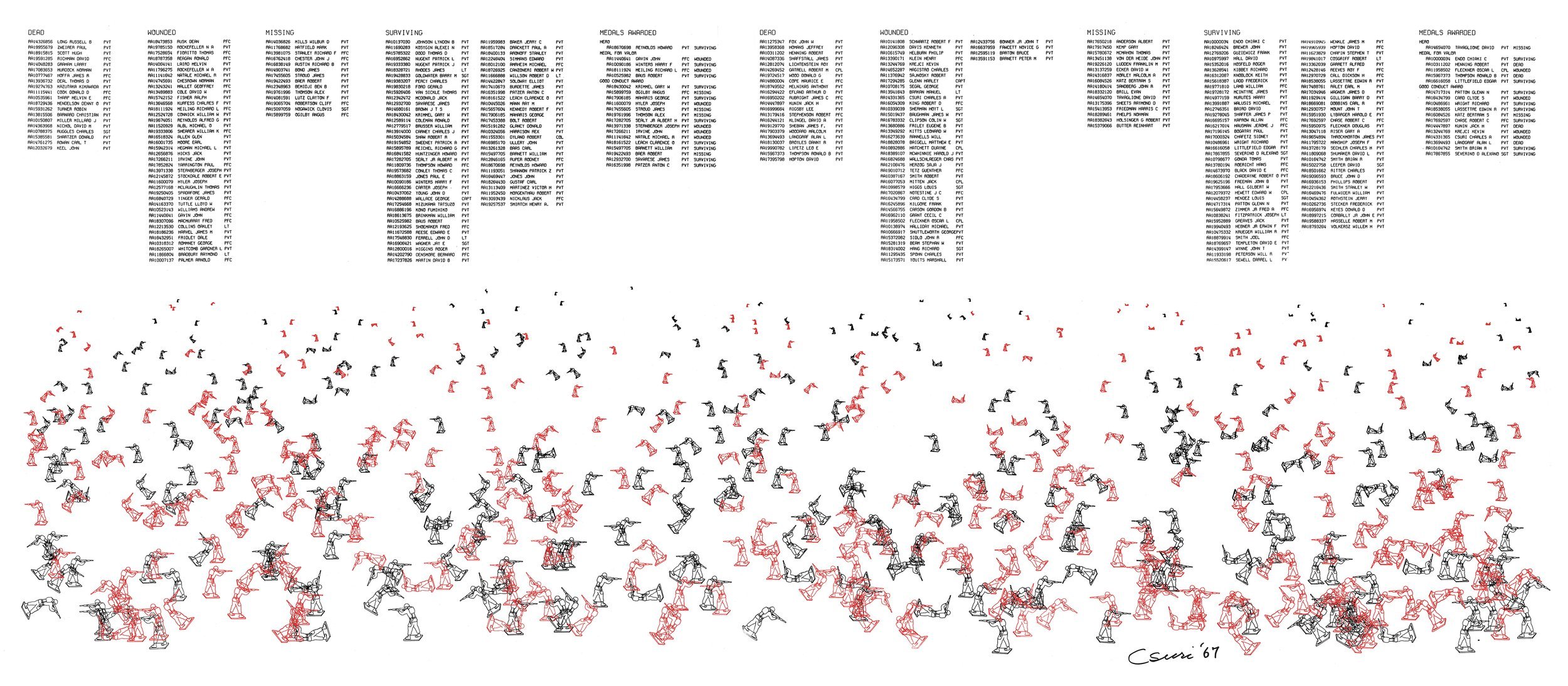

Csuri’s interest in randomness and game-like playfulness is exemplified in work, Random War (1967). In his work, he gave pictures of 400 soldiers along with a written list of their names to the computer. Using a pseudorandom number generator, the computer determined the distribution of the soldiers on the battlefield. The names became the soldiers under the categories of “Missing in Action”, “Wounded”, “Dead”, and “Medals Awarded”. Csuri used the soldiers’ names to personalize the randomness and chaos of war. Csuri also used pop icon names as well as presidents, and ordinary people to emphasize that war in life and death doesn't discriminate. This was an important conceptual and ironic commentary on the computer playing GOD in an age when computers were considered evil. For Csuri as a veteran, this artwork was pivotal in his search for meaning in his life-spanning digital artistic career.

MIDDLE PERIOD (1989-2000)

In 1990, Csuri became a professor Emeritus, retiring from his role at ACCAD to focus on creating digital art. During this middle period, he started experimenting with combining traditional drawings and paintings with evolving proprietary software developments. He brought his drawings into a three-dimensional computer space and used techniques like texture, bump mapping, and embossing.

Csuri describes his works as “organic looking”, suggesting that the use of traditional media helped to remove the sterile feeling of the mechanical computer forms. Developing the technique called texture mapping, he wrapped the virtual models with his oil paintings. The result is playful and focuses on the beauty and elegance of life.

A good example of this period is A Childs's Face. Csuri created a thick application of oil paint, that he wrapped around the computer-generated bust head that appears to be emerging from the background. Csuri plays with positive and negative space in a strong mix of pattern, color, and three-dimensional texture. Csuri also applies this technique with his drawing in The Hungarians.

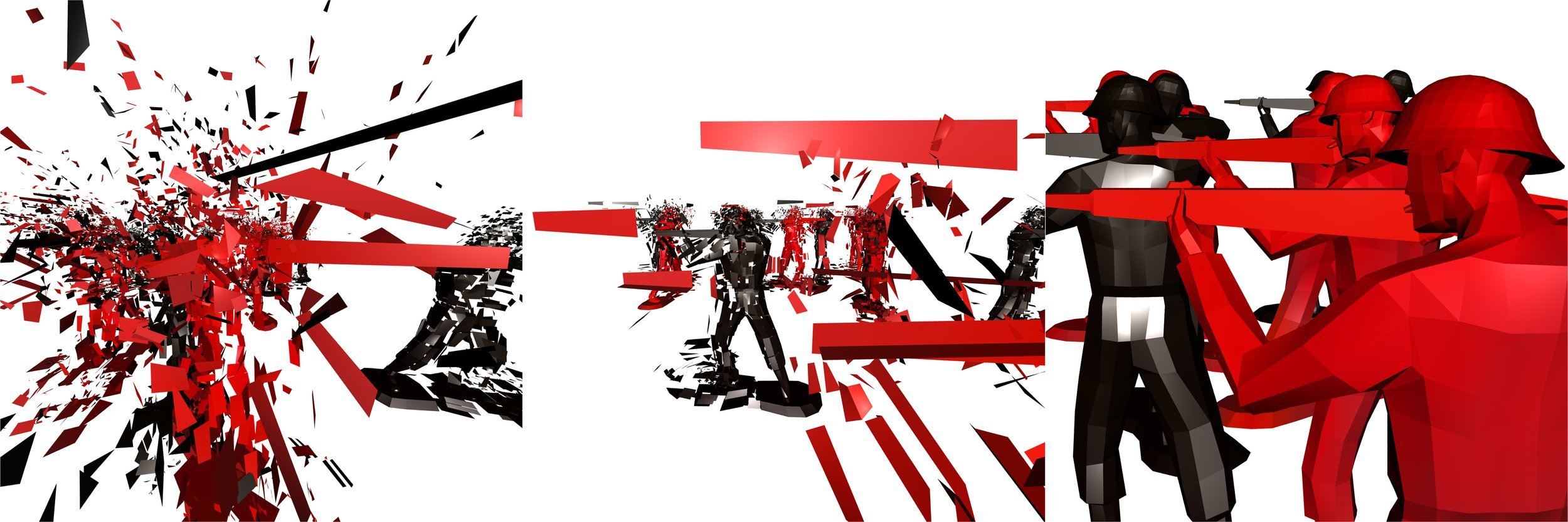

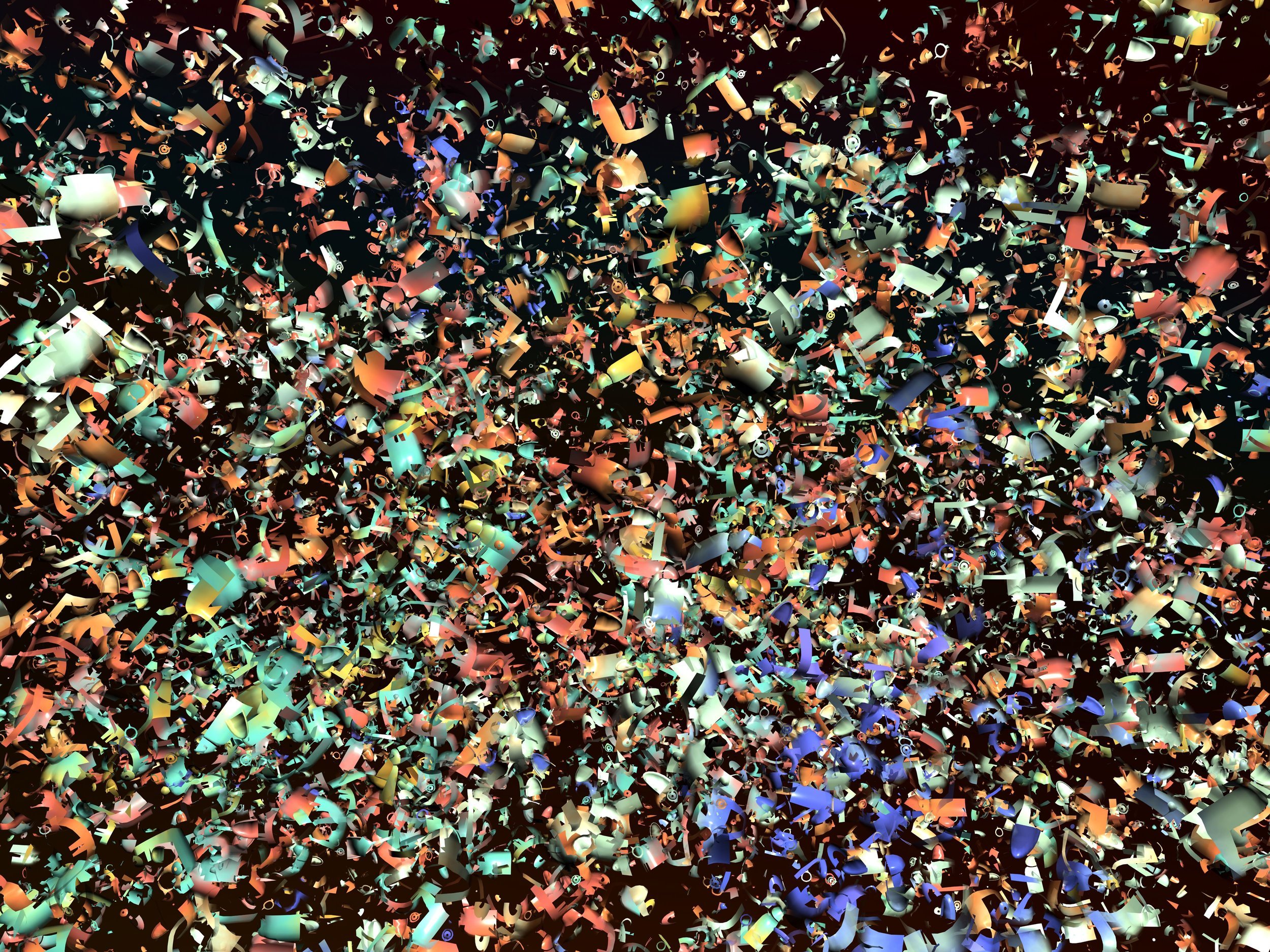

During this period, he continued to define artistic tools in collaboration with computer programmers through the development of custom software programs. Some of his core programming tools were the ribbon tool, the fragmentation tool, and the colormix tool. The fragmentation tool gave Csuri the ability to play with abstraction and representation. In the work, Cosmic Matter, Csuri fragmented digital models of classical sculpture where he simulated paint flying in the solar system.

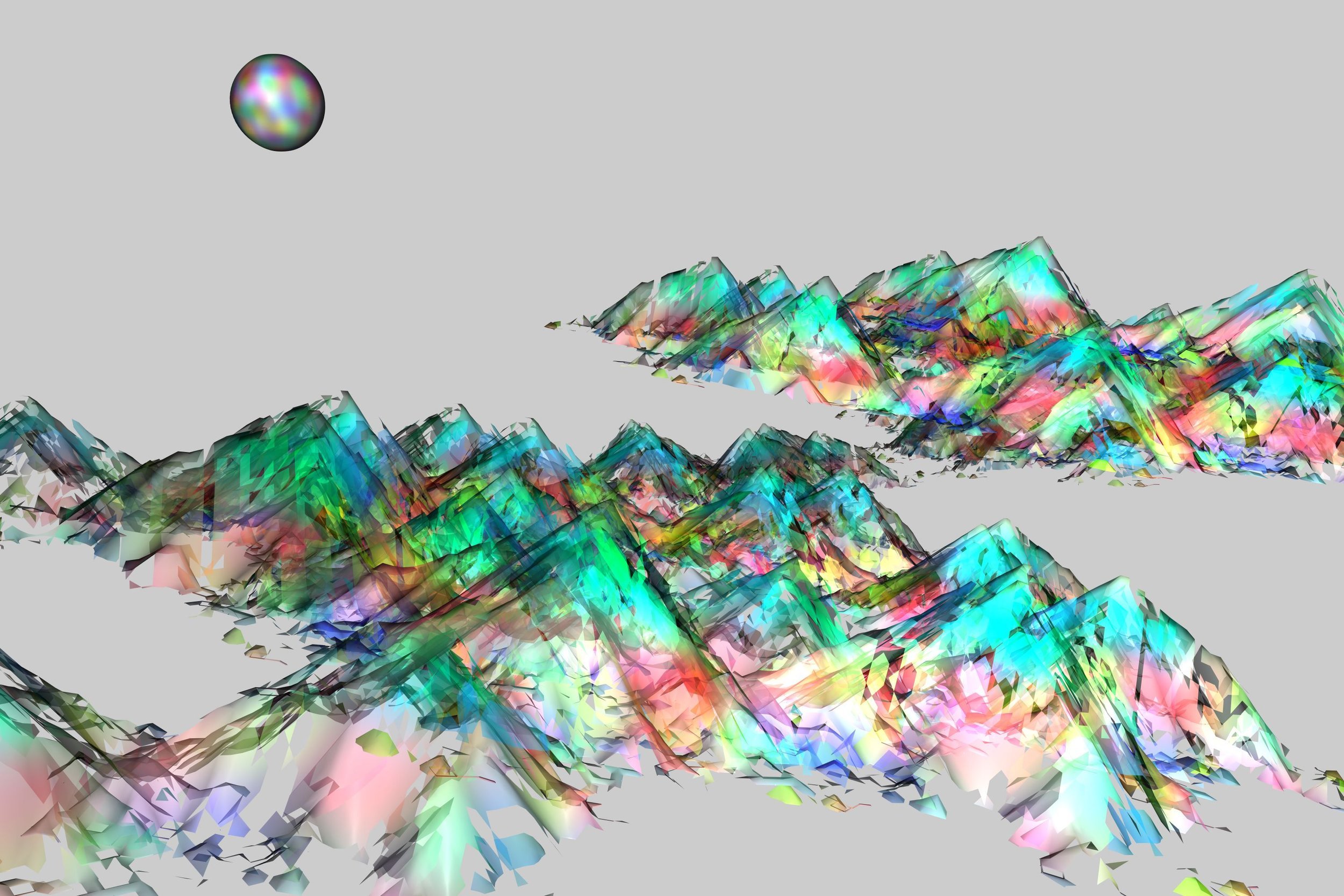

The colormix tool allowed him to define the location of specific colors and create color spaces through which Csuri can place or move his objects. In Wonderous Spring, he used prismatic colors in a transparent layering of forms.

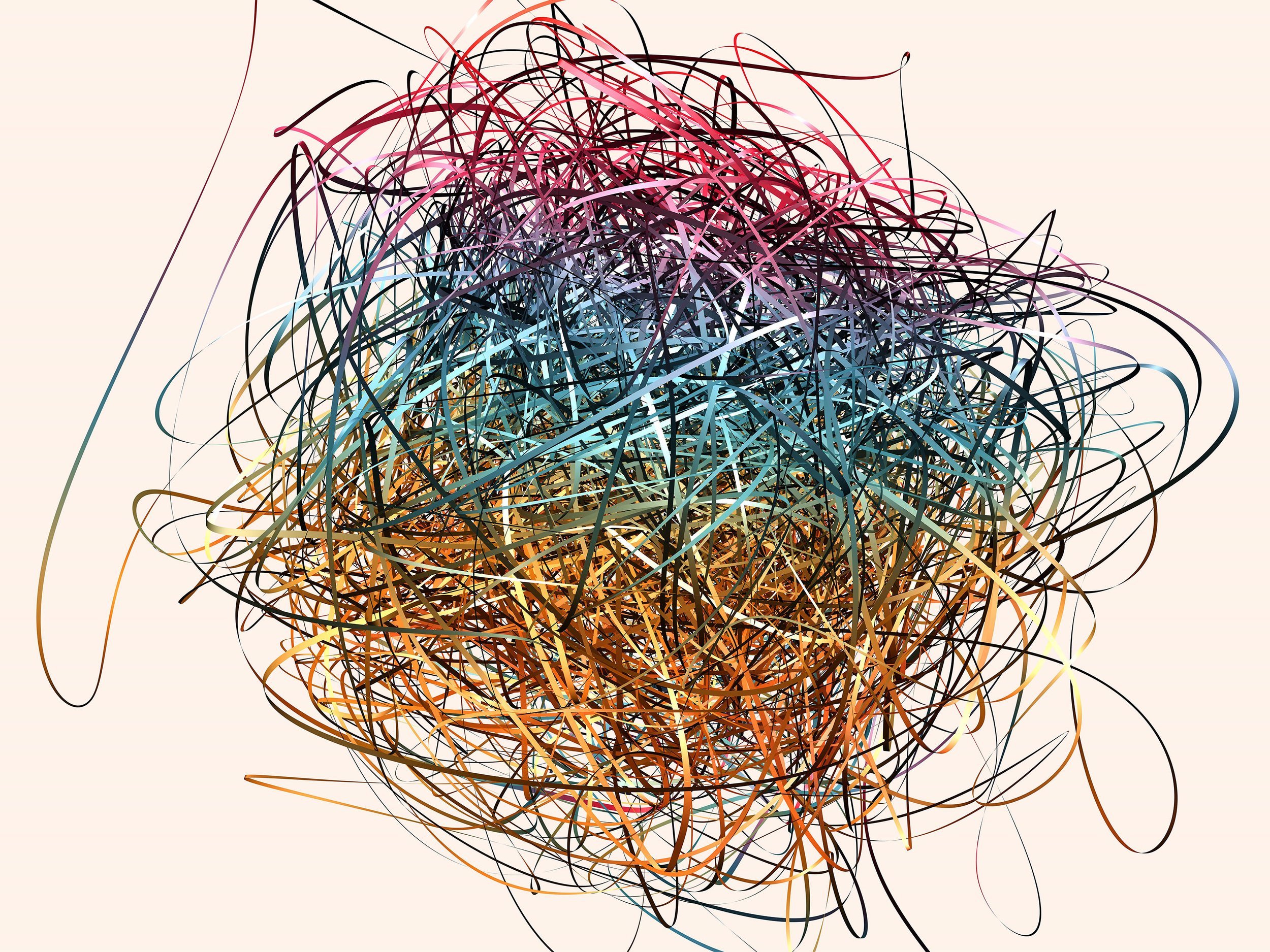

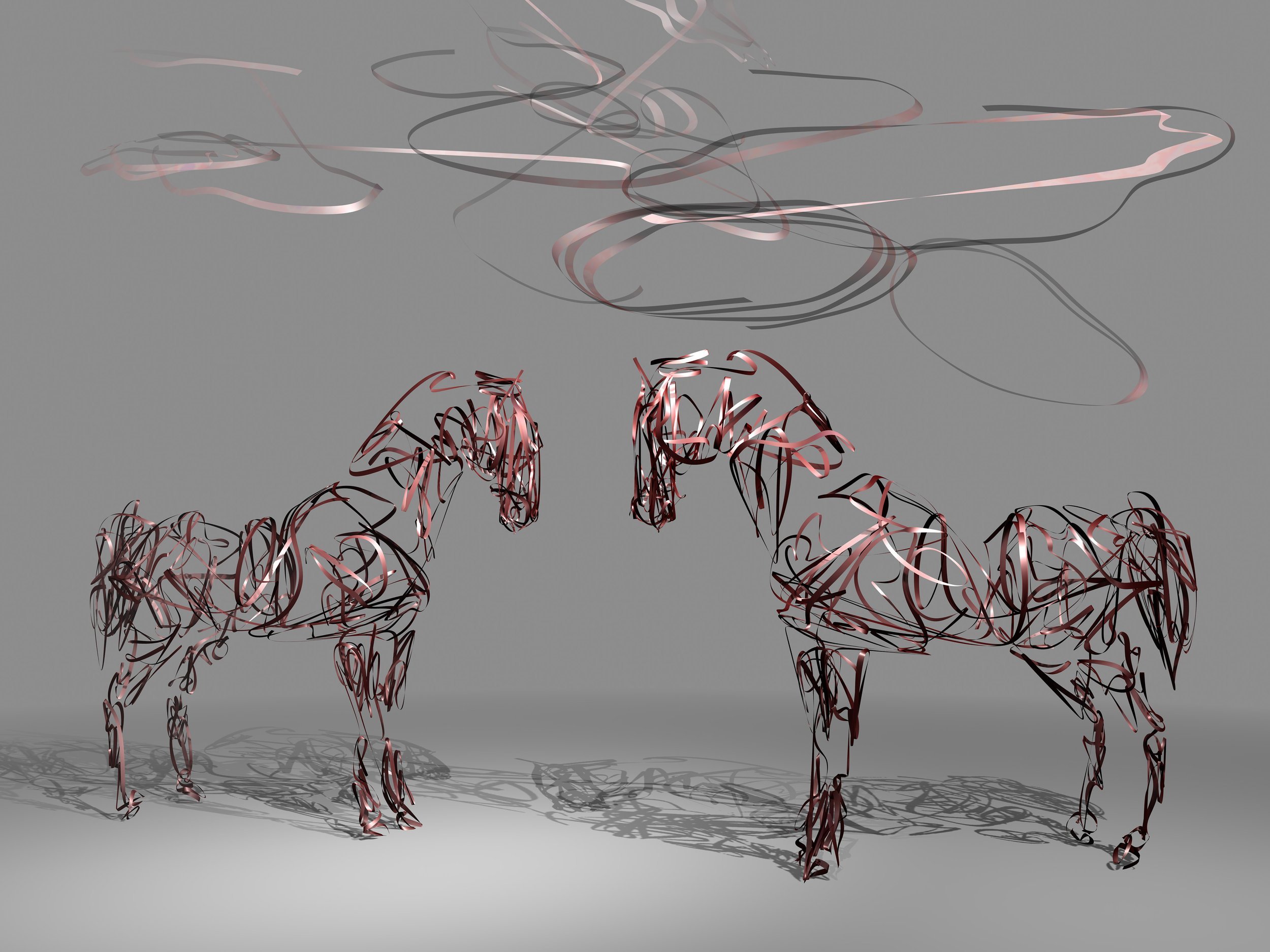

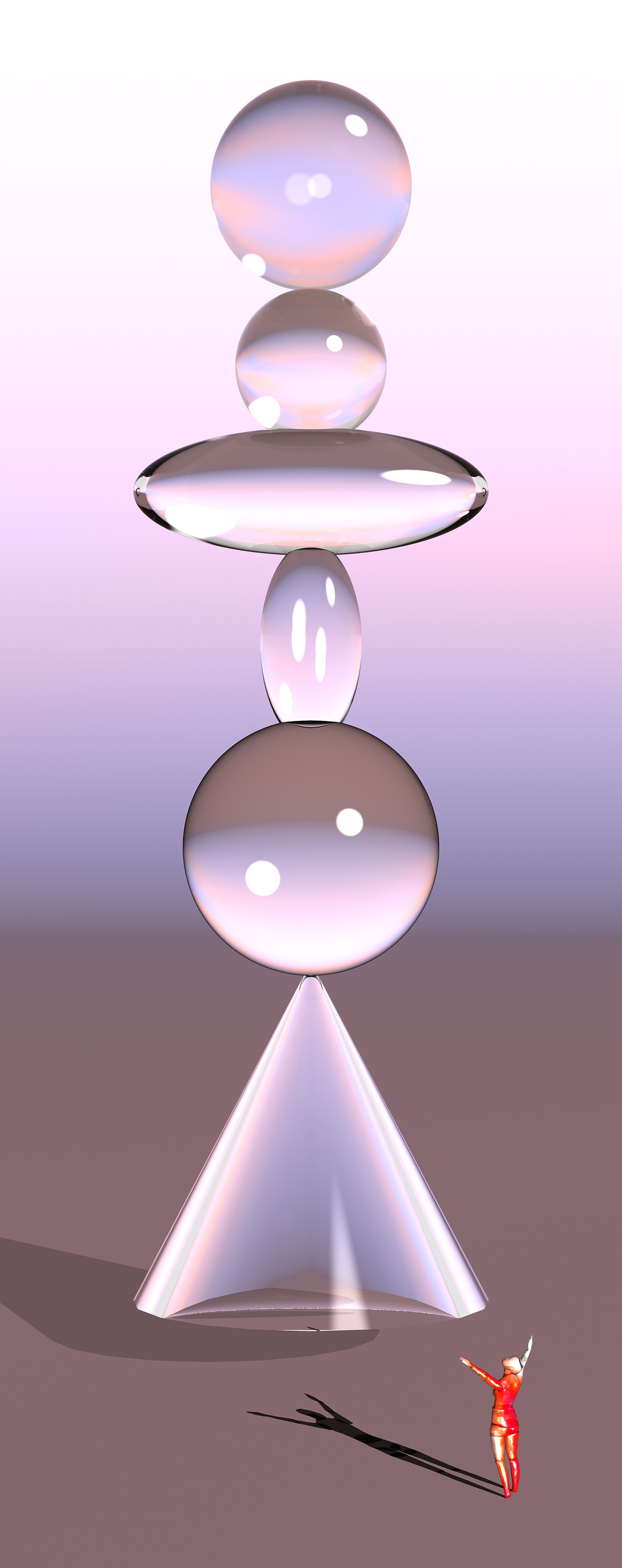

Csuri wanted to “draw” in 3 dimensions so he spearheaded the development of a ribbon tool that appears to draw calligraphic lines in the three-dimensional space. Csuri has used this tool to create works, such as Wire Ball and Horseplay. Another of his digital developments during this period was his experimentation with the interplay of light and transparency. His artistic vision was to create a reflective glass-like quality in 3D layers of transparency and objects. Balancing Act and Clearly Impressive

LATER PERIOD (1996-2006)

In his later period, Csuri uses the core artistic tools, which he created in the early 1990s and he continually modified them throughout his artistic career. One example was the implementation of his fragmentation tool to later apply to millions of objects in a random generative process. Csuri often functioned as an artistic editor while striving to uniquely create by computer something that could never be accomplished by hand. Celestial Clutter, Mosaic Lines, Festive Frame, and Abstract Ribbons. Nevertheless, the influence of the history of art and great masters continues to be an important part of his creative ambitions.

The father of modern art, Paul Cézanne had a significant influence on Csuri’s work and philosophy. Cézanne uses simplified geometric forms of the sphere, cylinder, and cone, forming them with light and color, composing a new order that transforms the visual language of art. Csuri spent years studying Cézanne's methods of manipulating color and light. He also redefines the objects in a three-dimensional space in which he creates new forms that synthesize realism and abstraction. Csuri further was influenced by the artwork of Leonardo Da Vinci and named many of his files Leo. As early as 1966, Csuri created The Leonardo Da Vinci Series with an IBM 7094 and drum plotter he transformed The Vitruvian Man by computer. He was inspired by concepts like Chiaroscuro and Sfumato as seen in Light_0008. where the smoky quality blurs contours so shapes emerge in an atmospheric quality. Reference to Cezanne's color in Landscape Two.

In Venus in the Garden Frame 73, from the Venus series, Csuri uses the famous Greek sculpture of Venus de Milo with his artistic set of parameters that control light, color, transparency, objects, camera position, and distances in a generative process. Here Csuri explores the mysteries of ancient myths and the evolution of organic forms. The sculpture is embedded in repeating and juxtaposed decorative motifs of ribbons, leaves, and flowers that blur the line between the figurative and the abstract. The interplay of elements in this algorithmic painting creates a rhythmic balance in an organic composition.

Origami Flowers is another example of the influence of traditional art history in Csuri’s art. The clump of irises is a reference to Csuri’s admiration for Japanese art and Van Gogh’s Irises. The work is a mathematical object constructed from polygons, in three-dimensional space with a light source placed by the artist. It consists of a complexity of shapes and lines, the intensities of light and dark colors, and the spatial depth resulting from multiple overlaps of material.

In the 1960s, Charles Csuri began exploring the use of randomness and chance in his art, as seen in works such as "Random War" and "Feeding Time." In the 1990s, he returned to this interest and created a series of generative art pieces known as the Infinity series. These works were generated using computer algorithms and mathematical equations, resulting in unique, endlessly repeating pieces. Csuri created three-dimensional environments composed of geometric forms, colors, lights, and shadows, assembled from thousands of fragmented objects. The overarching theme throughout his career has been in search of artistic and conceptual meaning in every creation by image transformation.

Charles Csuri continued creating digital art and animation until the age of 99. He is recognized as a true renaissance man: an athlete, professor, artist, and revolutionary innovator who combined art, science, and technology as one of the first pioneers of the genre. As an inspiring visionary, he mentored 60 PHD digital art and programming students. They have and will continue his legacy as a pioneer in the field of digital art and animation. Charles Csuri will be remembered in the history of art as a founder of the digital art movement. His revolutionary pictures and animation have been showcased in international exhibitions. His artwork can be found in renowned museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art NYC, Pompidou Center Paris, Victoria Albert Museum of Art London, and ZKM Museum Karlsruhe. LACMA Los Angeles, California. Whitney Museum of Art NYC, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb Croatia

Browse the works of Charles Csuri HERE!

Interview with Swiss artist, Eko33 by Arltcollector.eth

The original article is published on www.arltcollector.substack.com on 6th December 2022.

The generative artist known as Eko33 has been making art with computers since 1999. From being featured at Venice Biennale to now having his own solo-exhibition, he has already become an influential and respected artist in the gen art and NFT communities alike.

It was my pleasure to interview Eko33 and speak with him on Twitter Spaces on November 30, 2022. We spoke about many things including his creative process and upcoming solo-exhibition happening on December 7th 2022, curated by Kate Vass. I think a blog post on the Kate Vass Galerie website, articulated it best about Eko33’s work.

In that, it, “focuses on clear geometrical structures while including non-obvious yet advanced and diversified algorithmic forms. His works have no recognizable subject matter, using elements of art, such as lines, shapes, forms, colors, and texture. He aims to create pure art using algorithms. Emotions conveyed by his work are evoked by an eloquent use of colors and saturation on top of a unique layering approach underlying the subjectivity and biases of the human condition.”

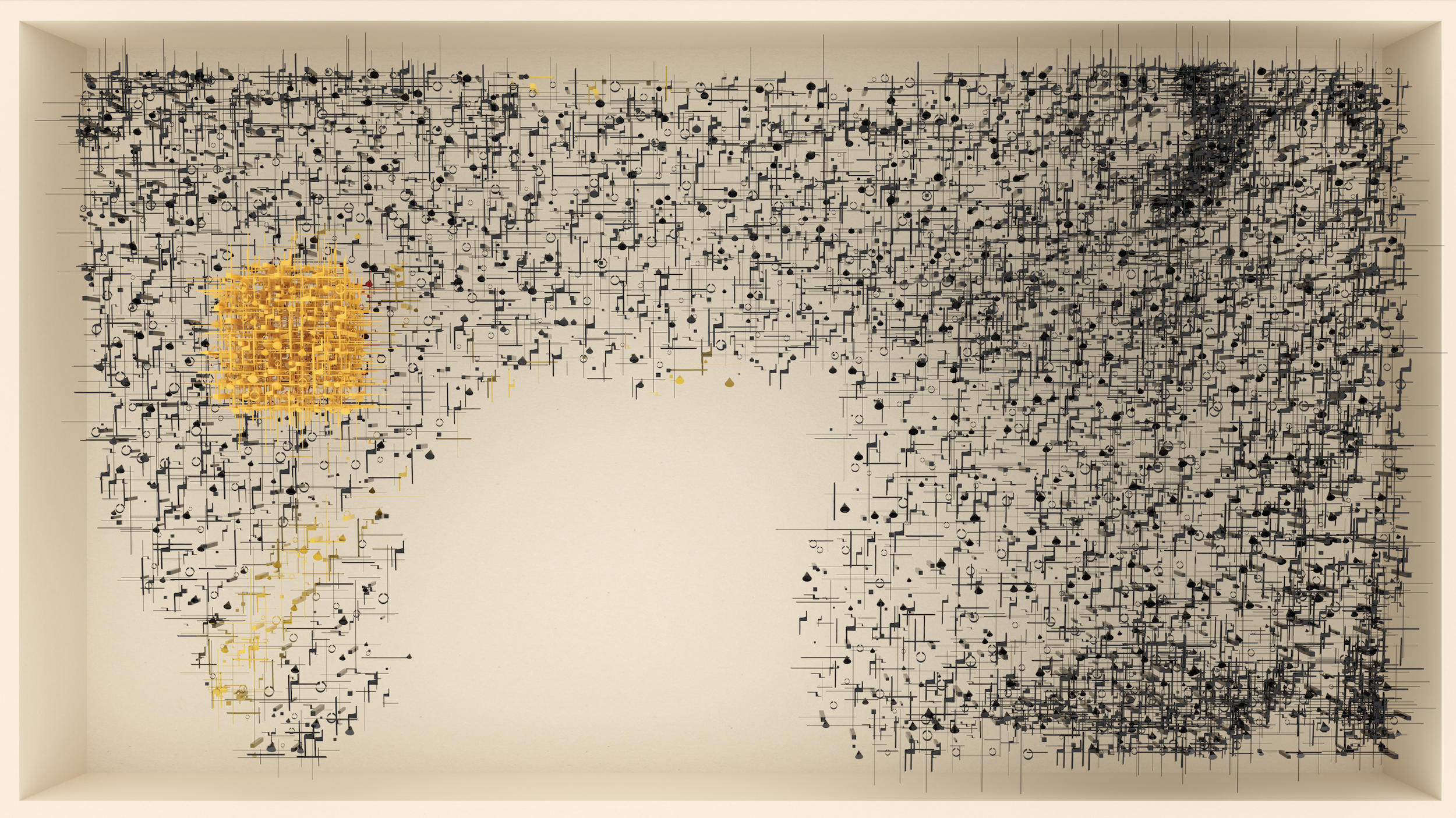

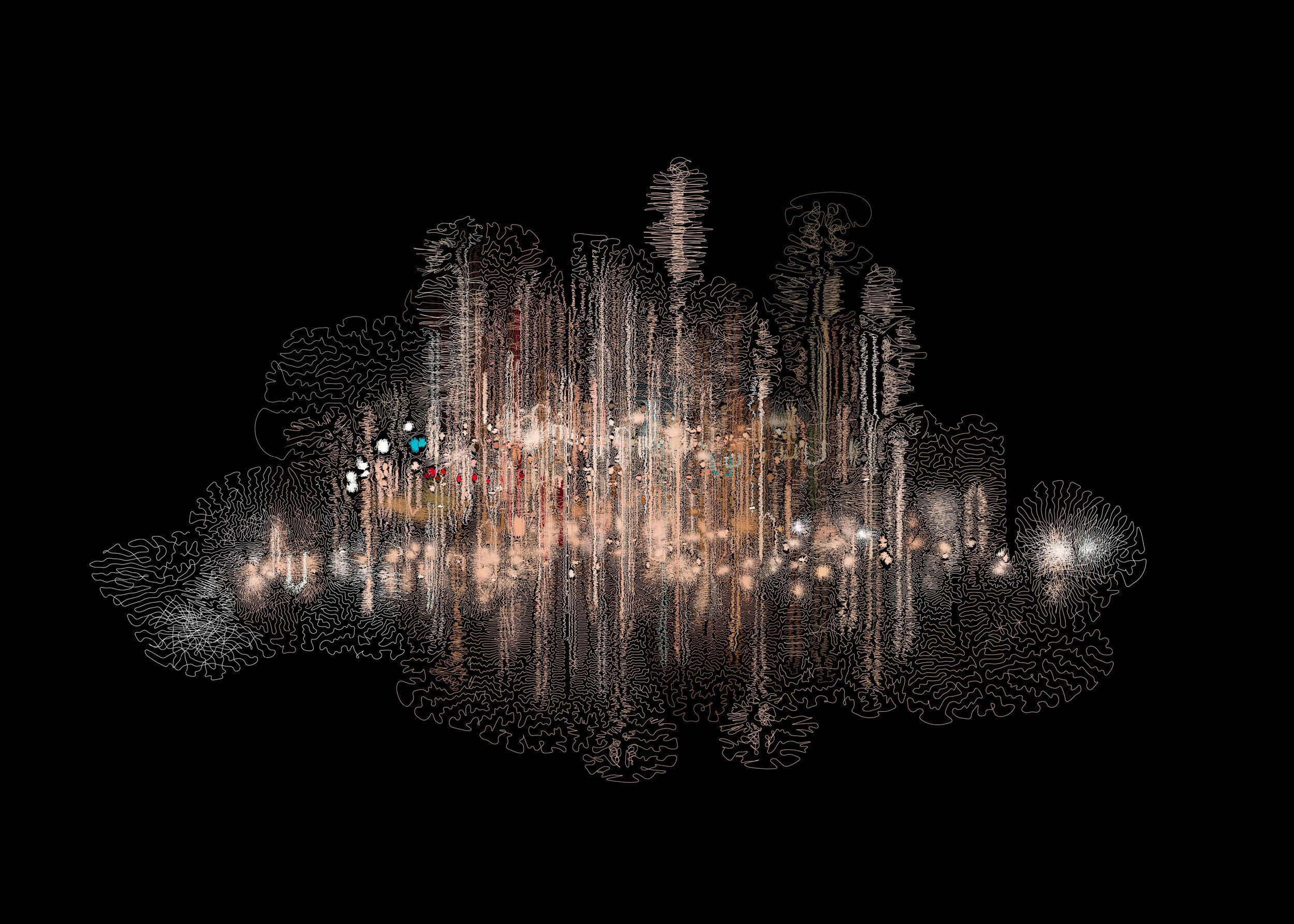

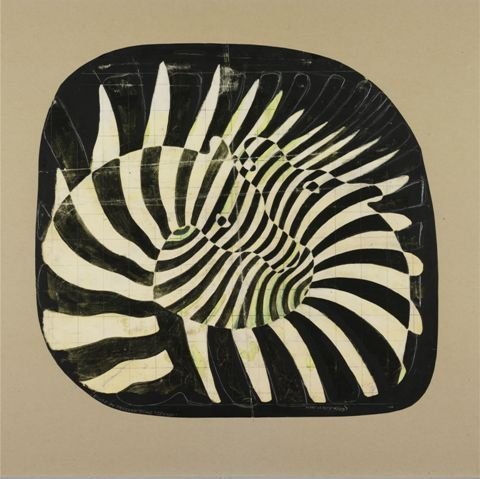

Eko33, Life Path #02, 2022, Unique NFT © Eko33

Eko, you’ve been featured in several exhibitions around the world this year, such as Venice Biennale, Art Basel 2022, and Cortesi Gallery. What was your experience like being a part of these shows?

It’s always a fantastic experience to meet real-life collectors and artists within international art fairs.

It’s interesting to see the evolution of the space within a concise period of time. I remember NFT art week Shenzhen and Art Basel Miami in December 2021 and how fast things changed and evolved when I was doing the opening of the Venice Biennale in Bloomberg’s Pavilion with Tezos at Venice Biennale and Art Basel Basel last May.

Traditional art galleries enter the space, technology, and know-how to display digital art is also making tremendous progress on a monthly basis.

Attendance for digital art keeps on increasing, I remember at Paris+ Art Basel how crowded the place was where NFTs were displayed.

Is there an event in particular that really stood out to you the most from this past year?

Each of them are very unique in their own ways. One of my best memories was looking at my long-form series being displayed alongside Herbert W. Franke, ‘Mondrian’ (1979) in Art Basel, Basel, and then having my work featured in Forbes magazine as part of the best of Art Basel 2022.

Is there a place you have traveled to or an event you’ve attended recently that inspired you enough to create something?

When I travel I always take a lot of pictures with my phone or a drone. I’m doing this because I use it as an archive for creating color palettes.

I travel extensively and even if I may not be cognizant of it all the time I’m sure it influences my emotions and mindsets. The first thing I do upon arriving in a new place is to look for interesting museums or bookstores.

When I worked on the long-form series called “Epochs” I started the project while being in Lisbon Portugal and I got fascinated by azulejos which turned out to be the starting point of a deep dive into the works of Sebastien Truchet and his famous “Truchet tiles” which turned out to be the core of this project.

Quick side note, where is one of your favorite places to travel and why?

One of the best places to travel to is going back home, I absolutely love Switzerland. I live in a rather secluded area in the swiss alps and I’m absolutely grateful each time I go back to discover the evolution of nature, I’m never bored contemplating it.

On a more "exotic" note, one of my favorite places is a french island called Corsica. It’s a jewel in the mediterranean sea with authentic nature and locals.

Eko33, Untitled series: Square #174”, 2022, Unique NFT accompanied by unique print on ChromaLuxe Aluminum with semi-gloss finish in size 1.2 x 1.2 m, Signed by the artist © Eko33

Your solo-exhibition opening December 7th 2022 in Zug, Switzerland is entitled, ‘Le monde non objectif’. How did you come together with Kate Vass Galerie to curate this collection?

Kate had the idea for me to initially show two collections, one called “artefacts” and the other called “Untitled”.

Then we took time to review everything I created over the past 18 months and we believed it would be a good idea to expand the scope of the exhibition and to include more facets of my work.

When did you begin working on this body of work?

It’s a rather recent body of work, the “oldest” pieces showcased are from projects which started 2 years ago.

I read that coding is usually the end of the process for you when creating something. Can you explain in further detail a little bit about your creative process and how you spend 80% drawing and only 20% actually coding?

I’ve been collecting a lot of mid-century furniture and old magazines from this era. I also enjoy collecting and reading art books.

The first step of my process is going through all these references, bookmarks from previous readings, etc. It can be literature, non-fiction, research papers, or drawings I’ve made by hand in the past.

My process can also evolve and change over time. I then draw a lot, identify color palettes, and collect more references.

After this, I start coding. Usually, I spend most of my coding time pushing the code to its limits as well as identifying the space of parameters suitable for the project. I like to anticipate as much as I can while leaving space for randomness.

I like to say that I work between control and randomness.

Eko33, Monster Luck 00, 2022, Print on paper, Size: 40 x 40 cm, Signed by the artist, Edition of 5 each © Eko33

So, I’m curious to know, how did you first get into NFTs?

I’ve been in the crypto space for quite some time. Initially, I thought it was a scam but gradually I learned more about it. Usually, the more you learn about blockchain technology the more you understand its underlying potential.

The intersection of game theory, cryptography, decentralization, technological challenges, and network effects are really fascinating to me.

I first got into NFTs as a collector and then I naturally started minting my own work.

What are your overall thoughts about this space?

So many smart and passionate people in the same place are quite rare.

Of course, not everyone has good intentions but overall it reminds me of the thrill and excitement I went through when I saw the arrival of the internet.

I have to highlight your spontaneous tweets simply titled “Gm if you love computer generative art!” which is always accompanied by one of your thrilling works of art. How did this ongoing series come about?

Working with computers and machines can be a lonely adventure. To avoid cabin fever I like imagining that each morning I pass by my friends and say good morning to them with a big smile on my face.

This is exactly what I’m doing on Twitter while sharing my advanced work in progress at the same time. It’s also a way for me to show my collectors that I’m here and keep working hard on new projects.

Eko33, Untitled series: Portrait #6, 2022, NFT, Edition of 5 © Eko33

As an artist going into 2023, do you feel pressure or think it’s necessary to be more active on Twitter and other social platforms to promote yourself and your work?

I don’t know if it can be qualified as pressure because at the end of the day everyone does whatever they want. Having said that, I know it can be difficult for some artists to be here and active each and every day.

Sometimes your engagement could fluctuate and if you don’t have a thick skin you may start having doubts about what you do and even sometimes feel a bit depressed if the audience does not react as you would have expected.

Social media algorithms have no mercy and I quite enjoy this type of blunt reminder.

I agree. I've come to appreciate the algorithm. Looking back now, how has a computer and generative art evolved since you began creating it in 1999?

It’s day and night. In 1999 I remember having to learn as much as I could on my own. The Internet was still in its infancy. Finding a learning community was challenging to say the least.

From a technical standpoint, I remember IRCAM in Paris created a hardware midi interface to work with sensors. I spent the entire summer in order to be able to afford it. Nowadays you can DIY this type of hardware for less than 30 euros.

The Intel Pentium CPUs were revolutionary at the time but nowadays our phones are way way more powerful. What we do in real-time today was just science fiction in 1999.

From an artistic point of view, I’m a bit surprised sometimes to see some projects made in 2022 being quite close from what was made a while ago.

With all the new technology available today, I believe we should aim for more radical and ambitious innovation.

I’m really working hard to integrate electronics, laser cutters, 3D printing, direct GPU interfacing, and game engines such as Unity in my practice. This is my main focus and I hope I can present this type of generative art in the near future.

Did you ever imagine the world would eventually become so receptive to digital and generative computer art?

Not even in my wildest dreams. I’ve witnessed the evolution and growing interest in digital and generative art and it’s really an amazing breakthrough.

I’m especially happy for artists like Vera Molnar, Herbert W. Franke, and others who could see this change unfolding after decades of modest interest from the public at large for generative art.

Eko33, Untitled series: Horizontal #6, 2022, NFT, edition of 5 © Eko33

On that note, is there anybody you really look up to as an artist, past or present?

Ben Laposky, Michael Noll, Frieder Nake, Georg Nees, Sophie Tauner-Arp, Mark Wilson, Waldemar Cordeiro, Paul Klee, Sonia Delaunay, Kandinsky, Aurelie Nemours, Sol Lewitt, Attila Kovacs, Chuck Csuri, Johan Shogren, François Morellet, Robert Mallary, Bridget Riley, Josef Albers, Anni Albers

I was reading your blog posts like “The story of Anni Albers and her contribution to generative art”, as well as previewing your “probably nothing” podcast, which you host. What other things do you love to do when you’re not creating art?

I believe we never spend enough time with friends and family. I learned this the hard way when I lost my father because of a car accident when I was quite young.

When I’m not creating art and when I’m not with my friends or family I enjoy doing electronic music, especially generative electronic with eurorack modules.

I like the analog feeling of making music from a pure electric signal, patching cables, not being able to save them, and not using computers at all, just a bunch of obscure small modules combined together.

Eko33, Life Path #21, 2022, Unique NFT © Eko33

I love to hear about your passion for music. I must know, what are some of your favorite albums that you can listen to for inspiration when creating?

I listen to music all day long while creating new works, my tastes are all over the place. I absolutely love Hindustani music, of course, Ravi Shankar is among my favorites. Ambient music is also something I especially enjoy such as Brian Eno’s album called Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks.

Other legends such as Ennio Morricone, Frank Zappa, Pierre Henry, Luc Ferrari, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Tangerine dream, boards of canada, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Erik Satie, Klaus Nomi, Nicolas Jaar, Khruangbin, Jean-Michel Jarre, Apparat.

Lastly, I want to ask what you’re currently building that’s getting you excited.

Right now I’m entirely focused on the forthcoming solo exhibition curated by Kate Vass and displayed at unpaired. Gallery on December 7th in Zug. It’s going to be a great opportunity to discover my new series called “untitled”.

It has never been exhibited before and will be presented on a high-quality digital display as well as super high-quality physical pieces in large format.

In early 2023 I’m also going to have a very exciting project which hasn’t been announced publicly yet. All I can say is that I’m thrilled and super proud about it. I didn’t want to rush the project and it was worth it as the curation panel really liked it.

Next year I’m finally going to be more focused on using electronics and real-time interactive installations to create generative art.

I hope to be able to combine zero knowledge proof technology with creative and artistic use cases during live events with robotics, lasers, and real-time minting experiences.

It’s incredible to learn about how you got started in generative art, and to experiment with real-time interactive installations and new tech. You’ve come a long way in a short amount of time.

Your curiosity to innovate and execute new ideas is inspiring. It helps push the whole community forward.

We’re all looking forward to the release of your solo show and the future of Eko33. Next time we do this, I hope to visit you in the Swiss Alps!

‘Le monde non objectif’ Solo-exhibition by Swiss artist Eko33

Kate Vass Galerie is happy to present the solo show of a Swiss artist, Jean-Jacques Duclaux, aka Eko33, 'Le mode non objectif' which takes place in Zug, at unpaired. Gallery on the 7th of December.

At the beginning of the 20th century, artists began to free themselves from academic constraints, abandon pictorial aspects and experiment only with colors and forms. One of the first figures to abandon objective art was Kazimir Malevich who was a leading member of the Suprematism movement. He wrote his vision in his book, The Non-Objective World, which was published in 1927 as part of the Bauhausbücher series and it is referred to as a manifesto of Suprematism.

Malevich was among the first painters who attempted to achieve the absolute painting that was clear from every objective reference. The term, non-objective art, takes nothing from reality and emphasizes the “primacy of pure feeling”. In contrast to Constructivism, non-objective art opposes any link between art and utility and the imitations of nature. Malevich aimed to create pure art, using geometric forms, where the feeling was the determining factor, the one and only source of creation.

“Blissful sense of liberating nonobjectivity drew me forth into the “desert,” where nothing is real except feeling… and so feeling became the substance of my life.” - Malevich, 1927

The formal elements of non-objective art remain part of recent artistic practices. Many artists during the 20th century use exclusively geometrical forms and exclude every objective element. In the 1960s, the forerunner of generative art, Sol LeWitt, embraced the philosophy of ’non-objectivity’ by creating the geometric ’Wall drawing’ series. Technology provides even more tools for artists to explore the concept of absolute art.

Eko33, Library series, 2022 © artist

The works of Jean-Jacques Duclaux, also known as Eko33 focus on clear geometrical structures while including non-obvious yet advanced and diversified algorithmic forms. His works have no recognizable subject matter, using elements of art, such as lines, shapes, forms, colors, and texture. He aims to create pure art using algorithms. Emotions conveyed by his work are evoked by an eloquent use of colors and saturation on top of a unique layering approach underlying the subjectivity and biases of the human condition.

Eko33 has created digital artworks using computer code since 1999. His practice is focused on creating artistic software and processes which generate unique artworks. Far from letting computers do as they wish; he defines the artistic rules and gives space to controlled luck and randomness.

In his artistic practice, classical approaches play a major role. Coding is usually the end of the process as he allocates more than 80% of his time drawing on paper and only 20% on the implementations. After creating the algorithm and identifying the suitable range of parameters matching his artistic vision, he moves on to the final stage, adding another layer of code to build the texture and final touches of his artworks. He uses multiple computer languages such as Processing, P5.js, Python, VEX, GLSL, 3d rendering engines alongside the custom software he built. Sometimes he uses an old Commodore SX-64 to pay tribute to the pioneers

Opens on 7th December at 6:30 PM in Zug, unpaired. Gallery (Rigistrasse 2, 6300)

Listen to the Twitter Space Interview with Arlt Collector and Kate Vass here!

For more information click here!

DIMENSIONALISTI - CADAF NYC 2022

Kate Vass Galerie is pleased to announce the exclusive program for CADAF 2022, taking place in New York from 11-13 November. We will present the work of computer art pioneer Charles Csuri, as well as Ganbrood and Lucas Aguirre, who worked with 3D technology in their artistic practice.

Over the centuries, many artists have tried to depict our three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. The Italian Renaissance was defined by the synthesis of art and science, resulting in the acquisition of a three-dimensional perspective with the help of Euclid’s geometry. The illusion of three-dimensional depth was a major turning point in art history, allowing the development of more naturalistic styles.

Georges Braque, Mandora (1909–10), Tate © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

During the first decades of the twentieth century, major modern art movements, such as Cubism or Futurism developed a revolutionary new approach to representing reality. The aim of Cubist artists, such as Picasso and Braque, was to show different viewpoints at the same time, within the same space by breaking the objects into planes. The idea of the fourth dimension was one of the favorite subjects of mathematics, science fiction, and art. There are many historical arguments about how Cubists encountered literature on the fourth dimension, but there is no doubt that their art was influenced by the theory of Henri Poincaré and Maurice Princet. By the end of the 1920s, the temporal fourth dimension of Einsteinian Relativity Theory achieved widespread popularity. As a result, some avant-garde artists recognized that space and time are not separate categories as had previously been taken for granted, but they are related dimensions in the sense of the non-Euclidean conception. Like non-Euclidean geometry, the fourth dimension was a symbol of liberation for artists. It encouraged artists to depart from visual reality and to reject the one-point perspective system that was used for depicting three-dimension.

The non-Euclidean geometry and the new conception of space and time influenced a Hungarian poet, and art theorist, Charles Sirató. As an emigrant in Paris, Sirató was fascinated by modern art, especially by paintings with depth and sculptures with moving elements. In 1936, he wrote a manifesto in which he lumped all the avant-garde tendencies together as a single movement and he called it: Dimensionism. Sirató used the formula “N + 1” to express how arts (like literature, painting, and sculpture) have to absorb a new dimension: literature should leave the line and enter the plane, painting should leave the plane and enter space from two to three dimensions, while sculpture would step out of closed forms to four dimensions. The movement’s endpoint would be “cosmic art”, which could be experienced with all five senses. The manifesto was signed by many prominent modern artists such as Hans Arp, Kandinsky, Robert Delaunay, and Marcel Duchamp.

Although the movement has since been almost completely forgotten, the representation of three-dimensional and four-dimensional space has remained an important theme in art. In the second half of the twentieth century, technology provides artists with even more tools to experiment.

One of the fathers of computer art, Charles Csuri’s research and artistic vision led to advances in software that created new artistic tools for 3D computer graphics, computer animation, and 3D printing. His work, “Cosmic Matter” from 1989 is an iconic example of Csuri’s early development of artistic tools that pioneered the field of computer art and animation. In “Cosmic Matter”, Csuri invented, in collaboration with other programmers, a technique called “texture mapping” that allows him to map his oil paintings onto 3D objects and further created object fragmentation to look like animated paint flying through the air. Further, he uses an embossing technique long before image processing capabilities use in Photoshop. In this picture, Csuri combines his formal fine art training with his revolutionary technology. This work was featured in Charles Csuri's retrospective international exhibition in 2006, at “The Beyond Boundaries”, Siggraph in 2006, & IEEE Computer Graphics and applications in 1990.

Charles Csuri, Cosmic Matter (1989), Unique NFT + Unique original Cibachrome print (30" x 40"), signed by the artist

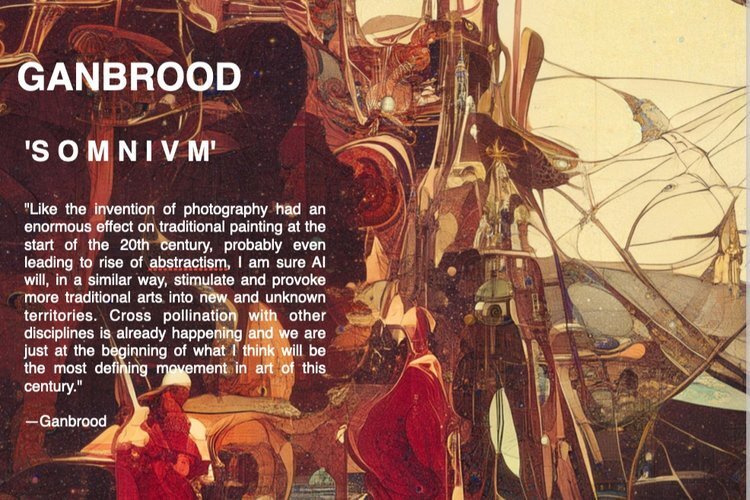

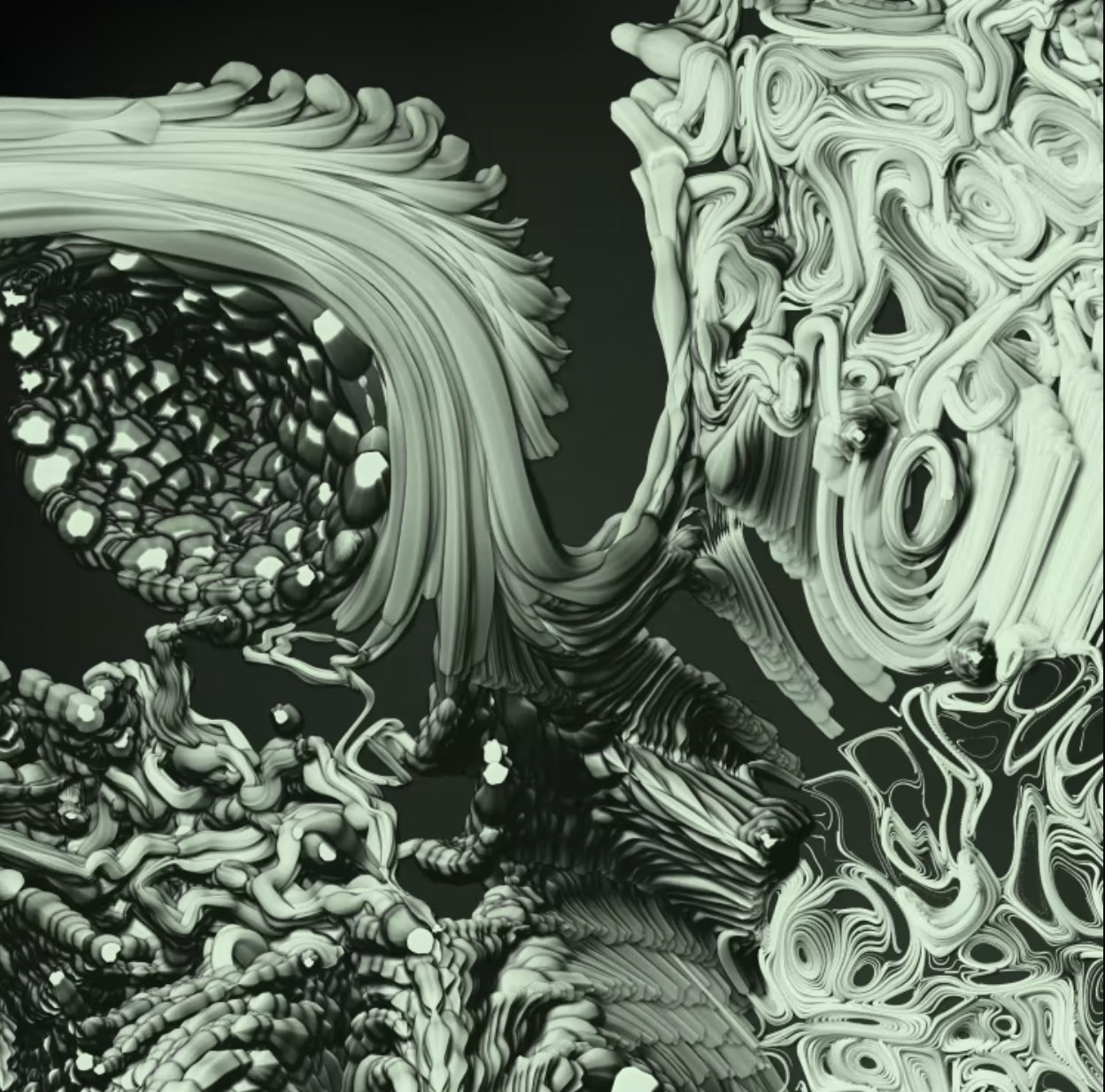

Spatial depth has always been a decisive element in Ganbrood's work. As a 3D animator in the early 1990s, but also his special effects for movies and later photography, dimensionality played a significant role as an essential part of visual language. In his latest series, SOMNIVM, he has combined visual themes that have inspired him since his youth: antic mythology, fairy tales, fine art, theatre, and science fiction. He used an Artificial Intelligence algorithm, GAN (Generative Adversarial Networks), to mix all these different visual elements. This neural network has enabled him to create more abstract, pseudo-figurative pieces that, at first glance, look figurative but, after close inspection, turn out to be abstract shapes. This series also demonstrates his penchant for illusions and trickery; the works ‘Skené’ and ‘The Displaced’ explore mind-altering effects such as pareidolia, apophenia, and synchronicity. The elements of contradictory mediums he used, like fresco paintings and photography and 3D, unbalance human visual recognition.

The Argentinian artist, Lucas Aguirre combines elements of physical reality in a digital space. His work, “Aparecida” is one of the first experiments with analog painting and 3-dimension. His painted strokes are scanned three-dimensionally and reconfigured using virtual reality. The result of these operations returns to the physical plane and be continued analogically a back and forth between traditional modes and new media. He understands digital tools as a possibility to subvert everyday elements and thus generate other visions. The virtual is a space of pure potentiality.

S O M N I V M by Ganbrood

“We ought not to ask why the human mind troubles to fathom the secrets of the universe. The diversity of the phenomena of nature is so great, and the treasures hidden in the skies so rich, precisely in order that the human mind shall never be lacking in fresh nourishment.”

Kate Vass Galerie is thrilled to announce the exclusive program S O M N I V M by Bas Uterwijk, aka Ganbrood. The program is a part of the group show ‘'Dear Machine, paint for me” that takes place on 27th October. The artist will be present, giving an introductory talk with curators of the upcoming group exhibition by Georg Bak & Kate Vass. For the first time, the artist will be exhibiting his works in physical and digital form, minted on post-fork ETH and accompanied by Fine Art prints on thermo-aluminium, signed by the artist.

When you see a shape in the dark, your brain tries to interpret it by mirroring the form, colour and material characteristics to your memory's frame of reference. Anything you ever saw and remembered could play a role in the pattern recognition process in your mind.

The synthetic image generation of Generative Adversarial Networks and Diffusion models works eerily similar to this human process: Input or random noise is compared to a vast trained library model of thousands of millions of fed images, and every possible image between these inputs, so-called 'Latent Space'.

Instead of using this method as a way to generate variations on existing pictures, Ganbrood uses these neural networks as a silicon muse to evoke and stimulate his expressive mind while at the same time interrogating the very essence of creativity: Could it be possible that a quality that was always considered as eminently human, is easily imitated or even reproduced by an algorithm? And when that is the case, are our fantasies and imagination may be controlled by mathematic expressions more than we would consider?

Like every artist is expanding on the work of their most revered predecessors, In 'S O M N I V M', Ganbrood uses visual themes that have always inspired him since youth: mythology and fairytales, theatre and film, painting and photography, videogames and comics. Drawing parallels in timeless variations of visual narrative by seeking their mathematical interfaces in latent space. Where a classicly trained artist like a painter or a sculptor would dig these shapes and symbols from memory, Artificial Intelligence is providing the present-day artist with the tools to draw references from synthetic storage, where the craftsmanship of brush and chisel are shifted to recognition and curation of artificial outputs.

Artificiality has always been a decisive element in Ganbrood's past work, whether using special effects and 3D animation for film or photographing actual events in a serene way that almost looked staged.

Always fascinated by illusions and trickery, Ganbroods oeuvre is a voyage of exploration into pseudo-figurative and mind-altering effects like pareidolia, apophenia and synchronicity.

This exploration takes an almost literal shape in "In this hard rock, whiles you do keep from me" and "This Island's Mine", where sci-fi elements of glorious space adventures meet Renaissancistic scenes. Set in a cinematic universe, the viewer can almost define the actors and decor of these who, after close inspection, turn out to be little more than abstract shapes.

Tragoidia and Les Filles du Roy are like stages. The elements of contradictory mediums like fresco paintings and photography or 3D are battling for the spectator's conclusion of how to interpret what is perceived.

Some artworks from S O M N I V M selection are exhibited at the group show ‘'Dear Machine, paint for me” from 27th October till 14th December 2022 at The Circle, Zurich.

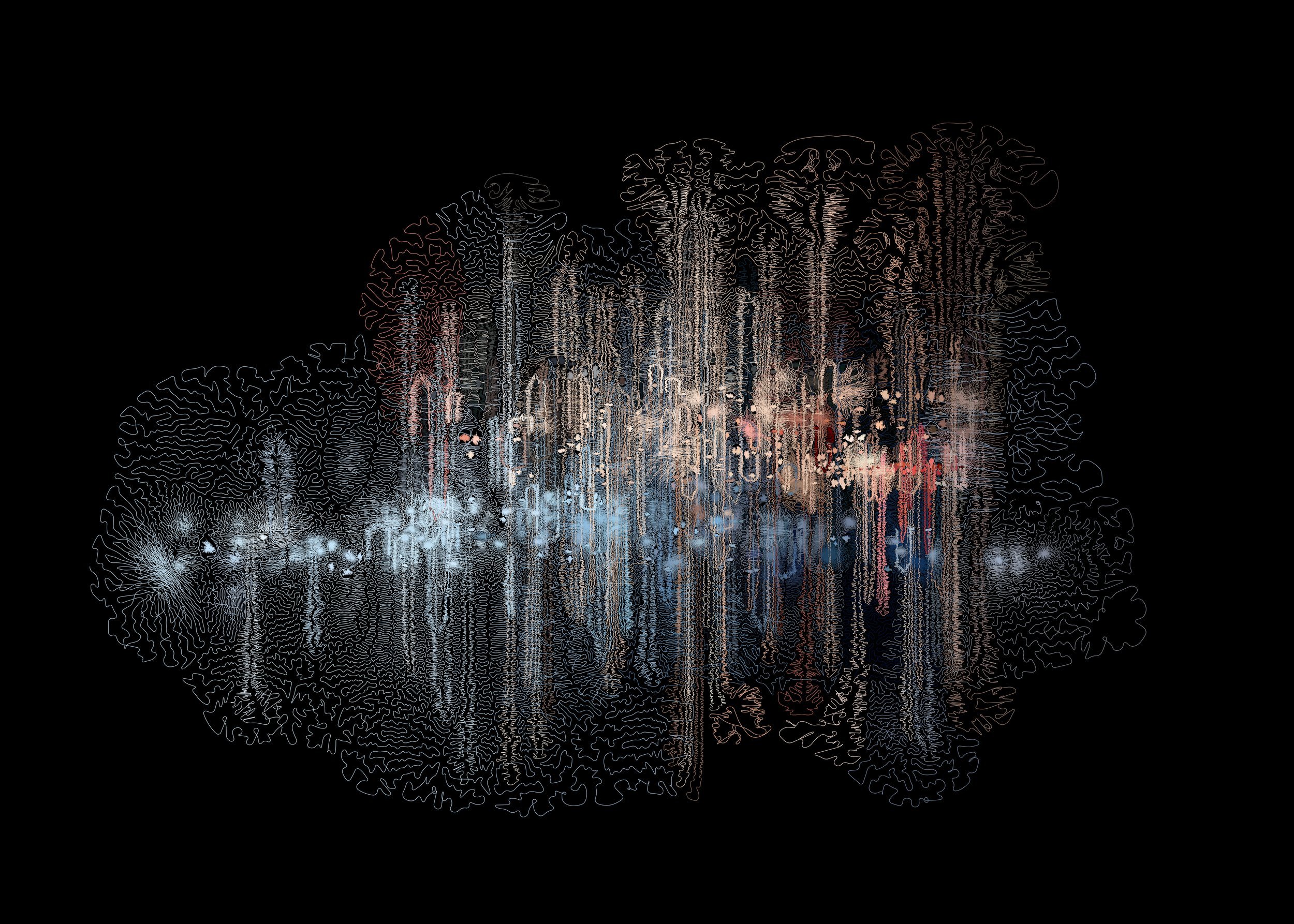

FROM 'ALTERNATIVES TO 'LYRICAL CONVERGENCE' BY ESPEN KLUGE

Lyrical Convergence comprises 100 new generative artworks, seeded with the same dataset from Kluge’s former Alternatives series, exhibited in both physical and digital form for the first time during the group show at Kate Vass Galerie, opening on 27th October 2022 in Zurich.

Espen Kluge is a true polymath: a composer, a visual artist, and a creative coder. He is fascinated by spontaneity and the exploration of semi-randomness in moments of improvisation.

This unique approach is reflected in his two series, which are closely related: Alternatives (2019) and Lyrical Convergence (2022). Both use the same set of data but two different algorithms. The artworks showcase the diversity of human perception, objectivity, and subjectivity, where we see the transformation from former Alternatives ‘figurative’ to abstractionism of ‘Lyrical Convergence’.

ALTERNATIVES, 2019

The alternatives series were exhibited for the first time in 2019 at the physical premises of Kate Vass Galerie. It marked a historical moment, where NFTs were shown as an artwork along with fine art prints as a solo show curated by Jason Bailey, aka Artnome. 100 unique portraits generated by JavaScript based on data collected from photographs taken in real by Espen since 2013 were on display as digital and physical art. Kluge’s portraits are monumental and structural, reminding us of the sculpture of Russian constructivists like Naum Gabo and Vladimir Tatlin. But in contrast to the sombre colours of the constructivist movement, Kluge’s works play with vibrant colours, where he questions the object and its characteristics, where vector-based lines serve a particular dynamic to describe the persona. His code takes photographs as input, loops through all the pixels in a raster image, chooses some at semi-random, and then engages those pixels by putting lines between them. Espen believes that the quality of each of his portraits comes from the fact that he writes by hand a new version of his algorithm for every portrait in pure Javascript.

Click below to browse the complete catalogue and the official website: https://alternatives.art

LYRICAL CONVERGENCE, 2022

Ravissement, oil on canvai, 1961 by Georges Mathieu

As a continuation of his experiments with the same data over the last 3 years, Espen developed a new algorithm that created a new set of works, the Lyrical Convergence.

With new growth algorithm Espen attempting to visualize the inner kismet of the Alternatives portraits. In contrast to the original series's geometric structure, the new sequence's result presents an organic-looking abstract form expressing intangible sensations.

The monochromic background, the centralized shape, the united lines, and the neat, calm colour palette are reminiscent of the art of Georges Matthieu, one of the fathers of lyrical abstraction.

The converging lines, which recall the cardiogram emphasis on colours, seem to interrogate the unconscious. Like a living creature on X axis, the linear progression dictates the dark landscape with its unique pace.

The artist adapts the immediate and direct approach to the new algorithm that brings into question the subject's position with respect to the object. Espen exalts it with the projection of his code with the coherent intensity to which the algorithmic execution of fragmentary castellations of lines, fields and colour imparted a maximum objectification. He makes it a place almost independent of the artist's existence, the code, and the manifestation of art itself. His series Lyrical Convergence is insemination in which subjective and objective, rather than being considered antonymous, hold a dialogue and form integration.

Like the European abstractionists, Espen’s works express something personal, vibrant, and entirely imaginative, in other words - lyrical.

Lyrical Convergence comprises 100 generative works, seeded with the same dataset from his former Alternatives series, exhibited in both physical and digital form.

Purchasing and Displaying NFT Art at Home: Expert’s Advice

September 7, 2022

Nothing beats an explosion of blockchain news to leave you wondering, “Um… what’s going on here?” That’s how I felt when I read about Grimes being paid millions of dollars for NFTs or Nyan Cat being sold as one.

The situation has only gotten more complicated in the year since NFTs became popular. Images of apes have sold for tens of millions of dollars, headlines about million-dollar hacks of NFT projects abound, and corporate cash grabs have only gotten worse.

All of this news may have left you wondering: what exactly is an NFT?

After consulting with a group of NFT experts, I believe I’ve figured it out.

Okay, let’s start with the basics.

What is an NFT?

An NFT is a Non-Fungible Token (a unique digital token), which many see as a certificate of authenticity, or a deed or proof confirming you own the right to display the above art on your wall or in your wallet (digital wallet). It might give you the right of ownership of the copy you bought (for your private use) but not necessarily over the ownership of the original artwork. Production rights and copyright are automatically retained by the artist unless otherwise specified in the contract. Regardless, non-fungible means ‘irreplaceable’ since each token is unique. And ‘Unique’ creates scarcity which, in turn, increases the market value for NFTs.

An NFT is technically an ERC-721 token on the Ethereum Blockchain. Another meaning of ERC is a ‘collectible’. The artwork is minted into the ERC-721 token. This token contains:

The historical information of any transactions plus artist information (including the artist’s public key) plus the number of likes (see the tiny ‘heart’ symbol above the image in the NFT).

A unique identifiable number = the token ID (click ‘chain info’)A picture of the art

A smart contract (the NFT is effectively a smart contract – you don’t need humans to sign signatures). Standard copyright law applies, and more specific conditions can be added to the description section.

A list of unlockables (additional optional extras e.g., a table mat or even a jigsaw with the art printed on it accessible via a link in the description.

NFTs can include art (paintings, graphics, videos, GIFs, songs, poems, tweets, posts even video games, virtual real estate, books), even birth certificates, and an awful lot more. Fungible means ‘replaceable by another identical item’. Non-fungible means are irreplaceable or unique. Another way of thinking about NFTs is as a process of documenting authorship and ownership.

Paul Smith from PR Smith

How can I minimize the risks of investing in NFTs?

Non-fungible tokens are taking the digital work with the many benefits they offer to both creators and investors. However, as NFTs are a relatively new asset class, they come with a unique set of risks. Before you invest in the market, you need to understand how to minimize the risks involved. Whether you are collecting NFTs for investment reasons or just for the love of art, there are two important steps you must always take into consideration: the security of the transaction and the storage of the NFTs.

One of the main NFT risks threatening investors is scams. Malicious actors may impersonate popular platforms, wallets, or well-known artists and sell fake artworks to unsuspecting customers. For this reason, it is always important to do your research on which wallet you are transferring your money to and where you are getting the money from. Checking the provenance of the work can also help you avoid falling victim to scams. Platforms usually provide guidance on how to make sure that the artwork was minted by a real artist.

Once you have purchased an NFT, you can move it to cold or warm storage. The warm storage, such as Coinbase or MetaMask, is connected to the internet, making it easier for hacking to take place. Even if the platforms use the most advanced security measures, with the failure to securely store passwords, hackers can easily steal users’ non-fungible tokens. If you want to secure sensitive data, we recommend using cold storage or hardware, such as Ledger or Trezor. These options are safer as all key information is on the device, protected by password or touch authentication, and more difficult for threat actors to access. The only risk of storing your NFTs in hardware storage is the loss or damage to the device. For this reason, many users own two cold storages, which is probably the best solution to protect your assets.

Agnes Flora Ferenczi from Kate Vass Gallery

Hungarians among the leaders of European art

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Hungarian artists were among the leaders of European art. From realistic genre scenes to avant-garde constructivism, to photography, many masterpieces left a mark on art history, both in Hungary and abroad.

Art before the 19th century

As an important Hungarian art historian, Lajos Fülöp argued in his essay, „The Task of Hungarian Art History” in 1951, Hungarian art had not existed before the 19th century: there was no art education or no influential great masters. Even the country was fragmented: at war with the Turks or with the Austrian army. Many of the greatest works from these periods had been produced by artists who came to Hungary from abroad or were born in Hungary but trained and worked in other countries. A good example of the latter is a still-life painter, Jakab Bogdány, who studied in the Netherlands and settled in England, or Ádám Mányoki, who had worked in Germany for princely patrons.

However, the 19th century was relatively peaceful. Hungary was part of the Austrian Empire and finally, the country was able to establish cultural institutions, such as National Museum (1802) and Hungarian Royal Drawing School (1871), and organize contemporary exhibitions (from 1840) for the public. With this institutional framework, the demand for Hungarian art and Hungarian painters started.

The list we compiled includes some of the most famous Hungarian artists who formed the art of the 19th and 20th centuries.

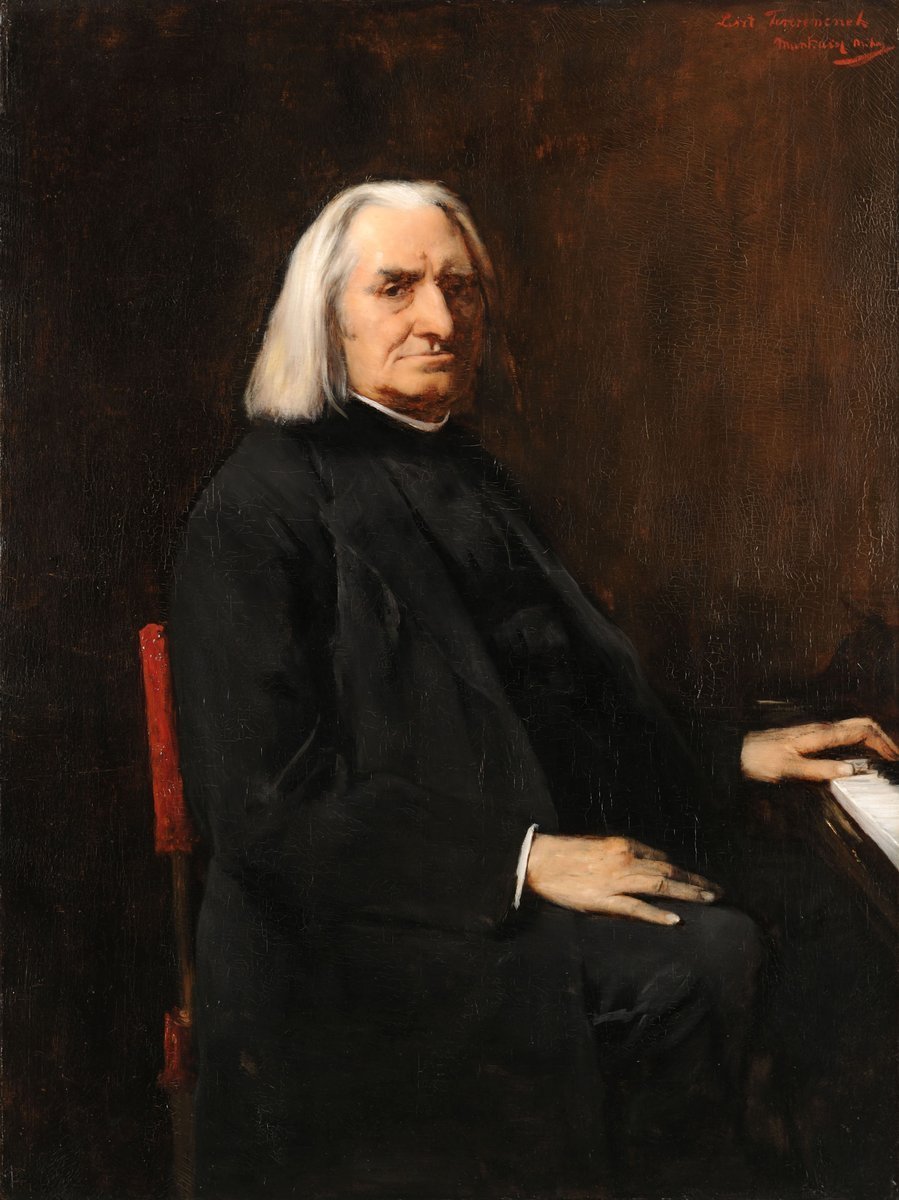

Mihály Munkácsy

Mihály Munkácsy was probably one of the most internationally well-known celebrities of the 19th century. He was born in Munkács, Hungary, he spent most of his life in Paris. He sold his realist works to wealthy European and American collectors, and his paintings are in collections such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Milwaukee Art Museum.

His first great successes were the „The Last Day of a Condemned Man”, for which he won a gold medal at the Paris Salon, and the „Woman Carrying Brushwood”. Both depicted Hungarian peasants and were painted in the manner of the Düsserdorf school. In the late 1870s, he also worked in Barbizon and painted richly colored landscapes such as “Walking in the Wood”. His realist portraits, including “Franz Liszt” or “Cardinal Haynald” were also painted during this period. In the late 1870s, he met an Austrian-born art dealer, Charles Sedelmeyer, who offered him a ten-year contract. This deal brought Munkácsy worldwide fame, wealth, and security. Sedelmeyer convinced him to create a large-scale Biblical series about the Passion of Christ. When Munkácsy completed the trilogy, the art dealer took the works on tour across Europe and United States. The paintings were exhibited in a dark room, without a frame, illuminated by candles. It was what everyone in Paris was talking about. After the financial success of the Christ trilogy, he started to create elegant salon genre paintings. Finally, his fame has washed away by the modernism of the early 20th century.

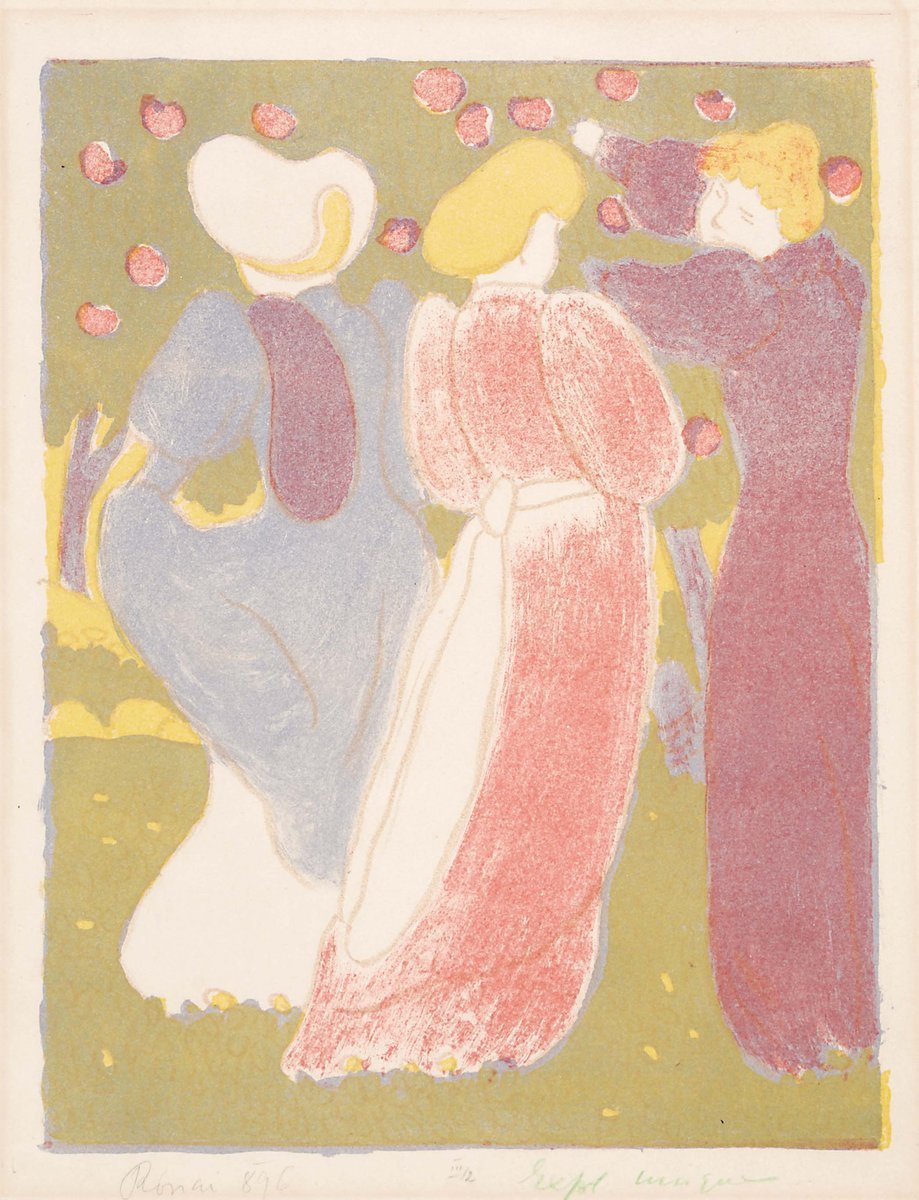

József Ripp-Rónai

József Rippl-Rónai was born in 1861 in Kaposvár, Hungary. He began his art studies at the age of 23 at the Münich Academy. In 1887, he was able to travel to Paris with a scholarship to learn from the most famous Hungarian realist master, Mihály Munkácsy. From the early 1890s, he sought his way among the era’s different styles, mainly Symbolism and Art Nouveau. He met the artists of Les Nabis and became a member of the group. Under their influence, he turned his interests to graphics, lithography, and applied art. One of his masterpieces from the Paris period is “Les Vierges”, which presents symbolic stages of women’s fate. From the middle of the 1890s, he started designing furniture and glasses, and tapestries, which led to commissions such as the design of the dining room of the “Andrássy Palace”. Later, he returned to Hungary and created a very special decorative style, called “corn style” ("Dressing women"), in which he applied a fluffy effect paint to the canvas.

Lajos Kassák

Lajos Kassák was the main figure of the Hungarian avant-garde movement. He was not only an avant-garde painter, but also a poet, novelist, essayist, and editor who brought together aesthetics and social criticism. Kassák first established himself as a writer when he published his first poem in 1908. In 1915, he published his provocative journal, “A Tett”, about activism and anarchism. After one year the journal was shut down by the Hungarian Ministry of the Interior. Kassák fled to Vienna in 1920 where he relaunched his magazine “MA”, on which he worked with Sándor Bortnyik, Béla Uitz and László Moholy-Nagy. His works, which were displayed in “MA”, show the great influence of the European avant-garde movements, combining Futurist, Constructivist, Expressionist, and Dadaist elements in the pieces. His introduction to the visual arts started with the so-called “image poems” inspired by Dada, where he displayed letters and lines aesthetically. From 1921, his art shifted towards a more reductive form of geometric abstraction. He called these works “picture architectures”, which were greatly influenced by the art of Malevich and Tatlin. In 1926, he returned to Hungary and continued editing and publishing leftist journals such as “Munka” (Work) and “Dokumentum” (Document). Kassák's innovative responses to social issues position him as a pioneer of modernity in art.

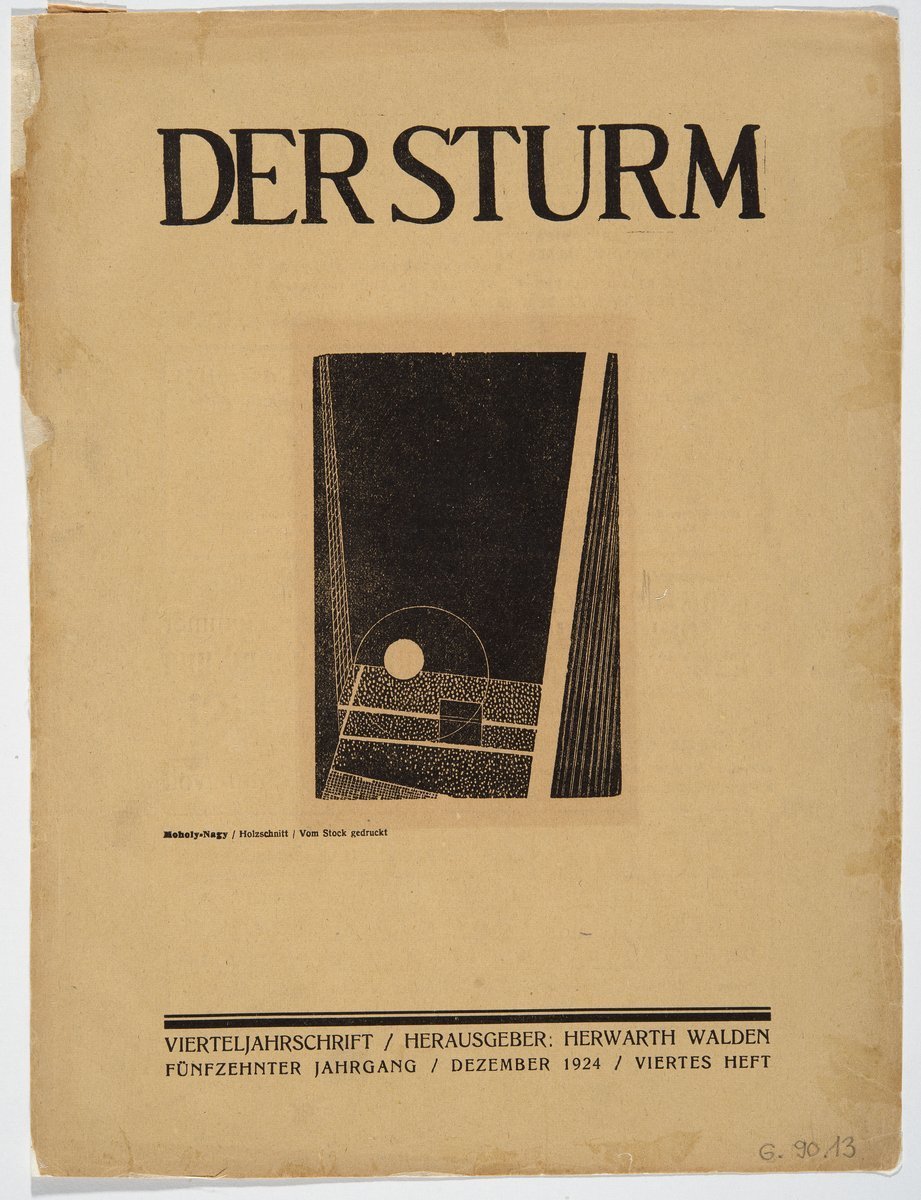

László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy was a Hungarian painter, photographer, and professor at the Bauhaus school. He was born László Weisz in 1895. Honoring his uncle, who raised him, he adopted the surname Nagy, and Moholy from the town he grew up. In 1919, he fled to Vienna and joined Lajos Kassák’s avant-garde group, publishing many of his works in the journal “MA”. His paintings from this period were constructed in geometric forms that are often overlapping, creating a careful study of transparency. Later, he relocated to Berlin, Germany, where he met photographer and writer Lucia Schulz, his first wife. Moholy-Nagy was fascinated by technology; he transformed industrial and urban elements into his paintings. In 1923, Walter Gropius invited him to teach at Bauhaus, which gathered many avant-garde artists, like Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Oscar Schlemmer. During this period, he was the co-publisher of the Bauhausbücher and designed typographies. Under the guidance of his wife, he also started experimenting with film and photography. Due to the political tensions, in 1937, he moved to Chicago and became the director of the New Bauhaus School. In the United States, Moholy-Nagy continued to work with art and technology until he died in 1946. His legacy influenced many different disciplines, including photography, architecture, design, and painting. His artworks can be found in major museums, like Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, and Art Institute of Chicago.

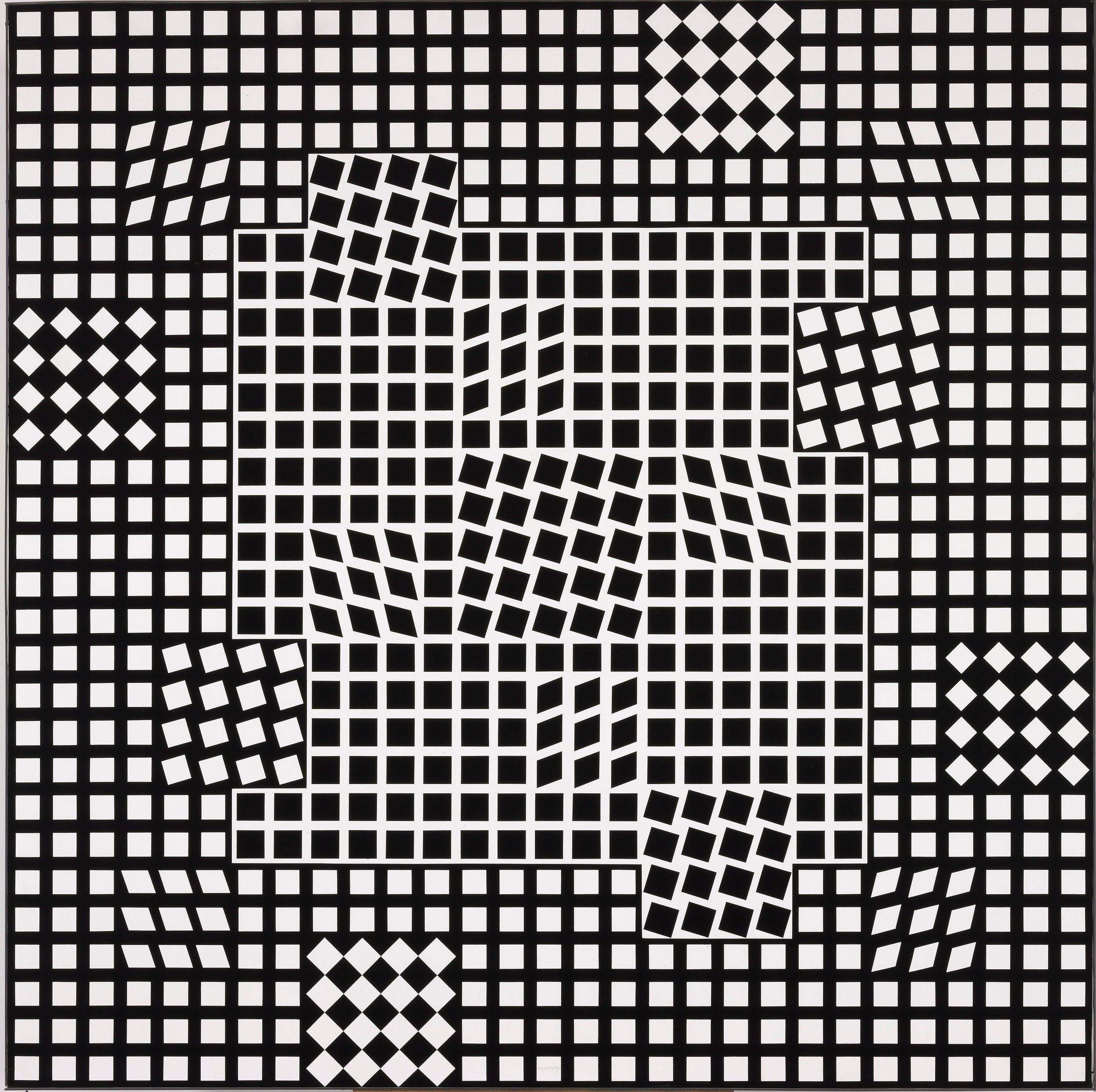

Victor Vasarely

Victor Vasarely was one of the leaders of the Op Art movement, a style based on optical illusion. He was born in Pécs, Hungary, in 1906. He began his art studies at Bortnyik Sándor’s private school, called Műhely Academy, which was mostly based on the theory of the Bauhaus school. In 1930, he settled in Paris, where he began his career in several advertising agencies. In Paris, he created abstract works, such as Zebra (1937), regarded today as the earliest examples of Op Art. In the 1940s, Vasarely experimented with styles such as Surrealism and Expressionism before arriving at his signature geometric, abstract, colorful style with a compelling illusion of depth. Later in his career, Vasarely experimented with kinetic art, creating many moveable sculptures. From 1955, he worked with a defined palette of colors and forms and started serial arts, an endless permutation of forms, and colors. Before his death in 1997, he founded several museums dedicated to his works.

André Kertész

André Kertész was one of the best-known photographers of the 20th century, renowned for his lyrical, elegant, and rigorous style. He was born in Budapest in 1894. In 1925, he published his first photograph on the cover of a local newspaper, Érdekes Újság. In the same year, he emigrated to Paris. He worked as a freelancer for numerous publications and met Piet Mondrian, Sergei Eisenstein, and many of the Dadaists. In 1936, after the rise of Nazism, he fled to the United States, to New York, where he began collaborating with magazines like Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Coronet, and organized solo shows at the Art Institute of Chicago and Museum of Modern Art New York. During this time, Kertész developed his fascination for capturing images of people in outside spaces such as parks, windows, and balconies. He loved using geometric lines and patterns, turning a street scene or object into something metaphorical and permanent. Kertész made a huge impact on other well-known photographers, including the Hungarian Robert Capa and Brassaï, who considered him a mentor.

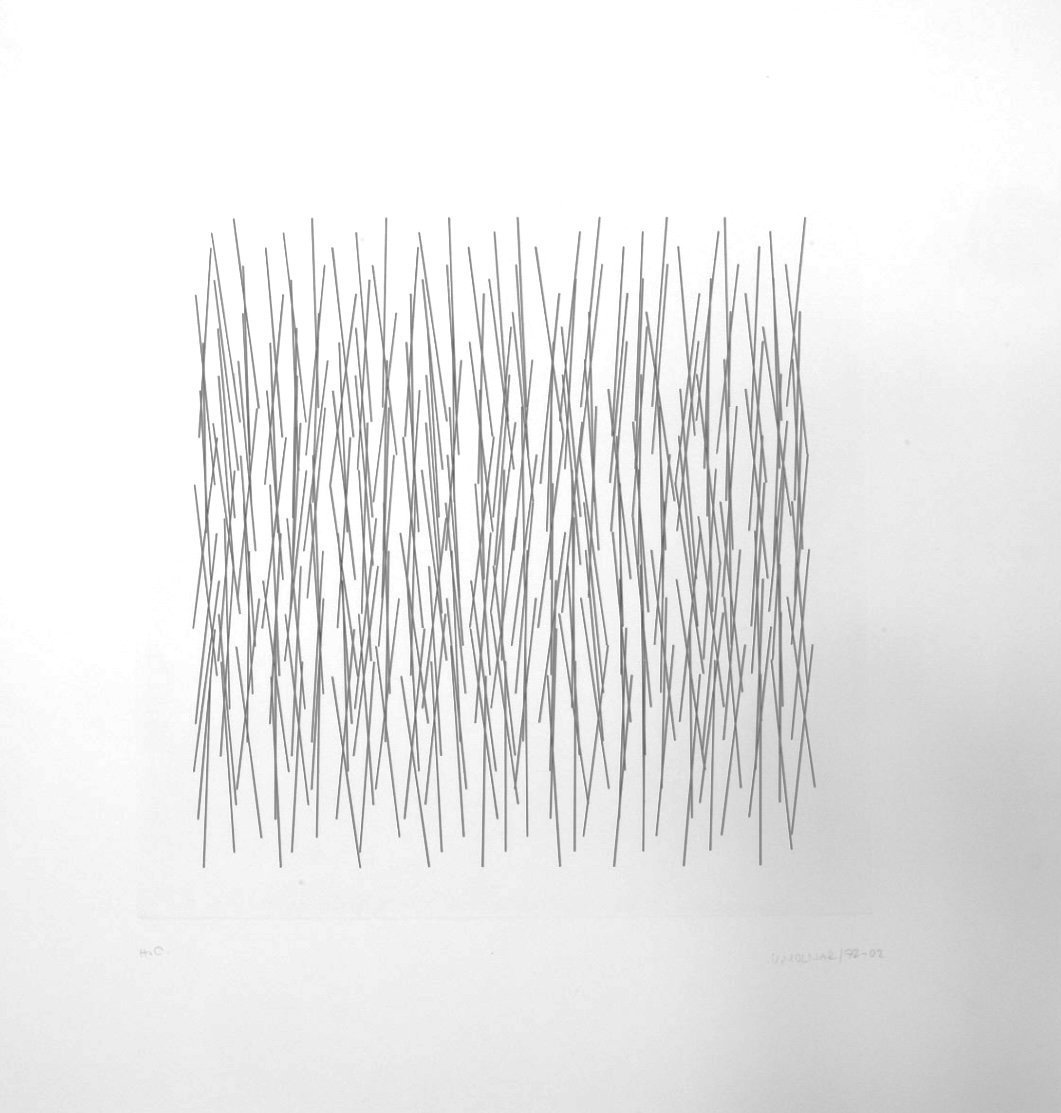

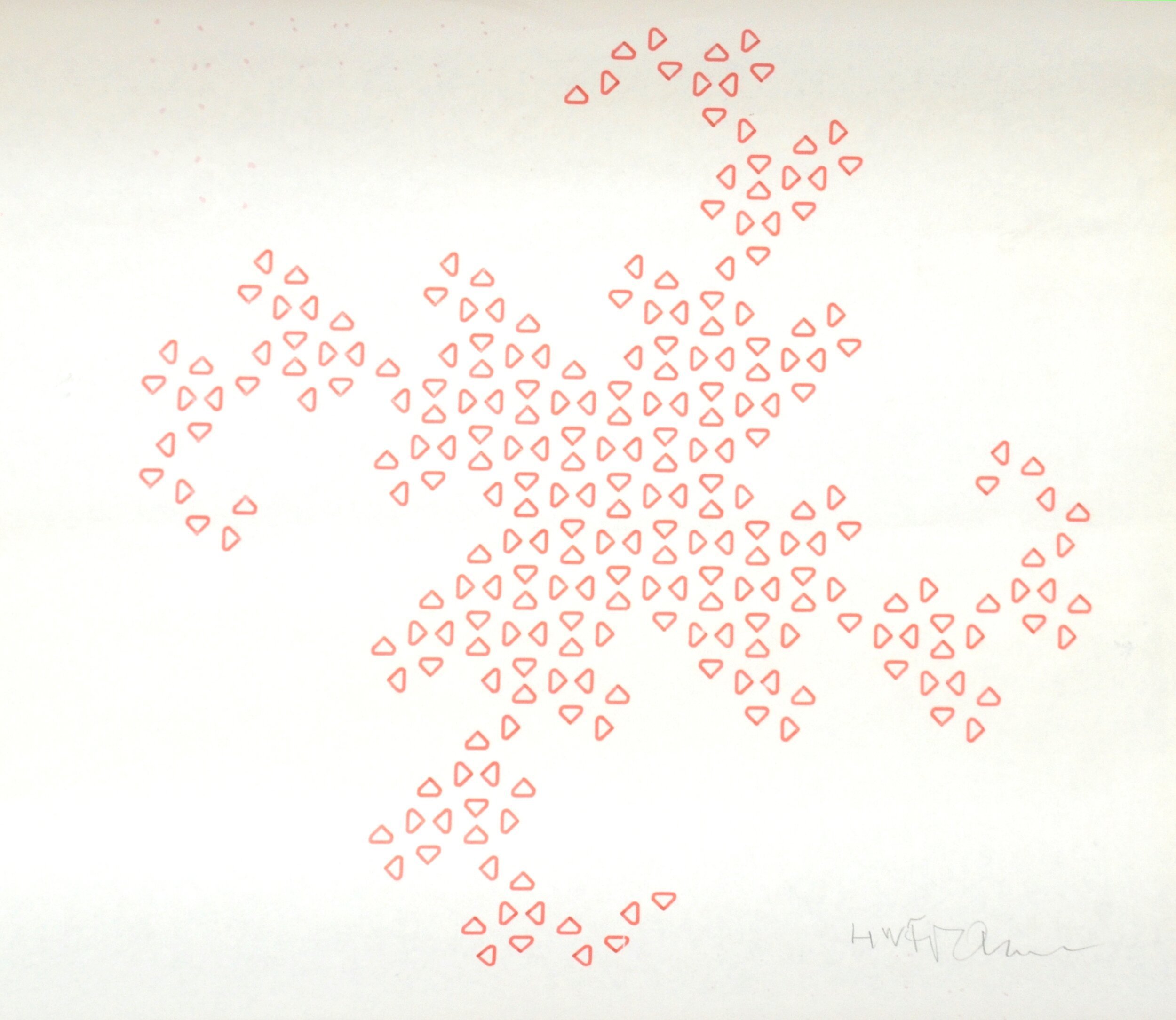

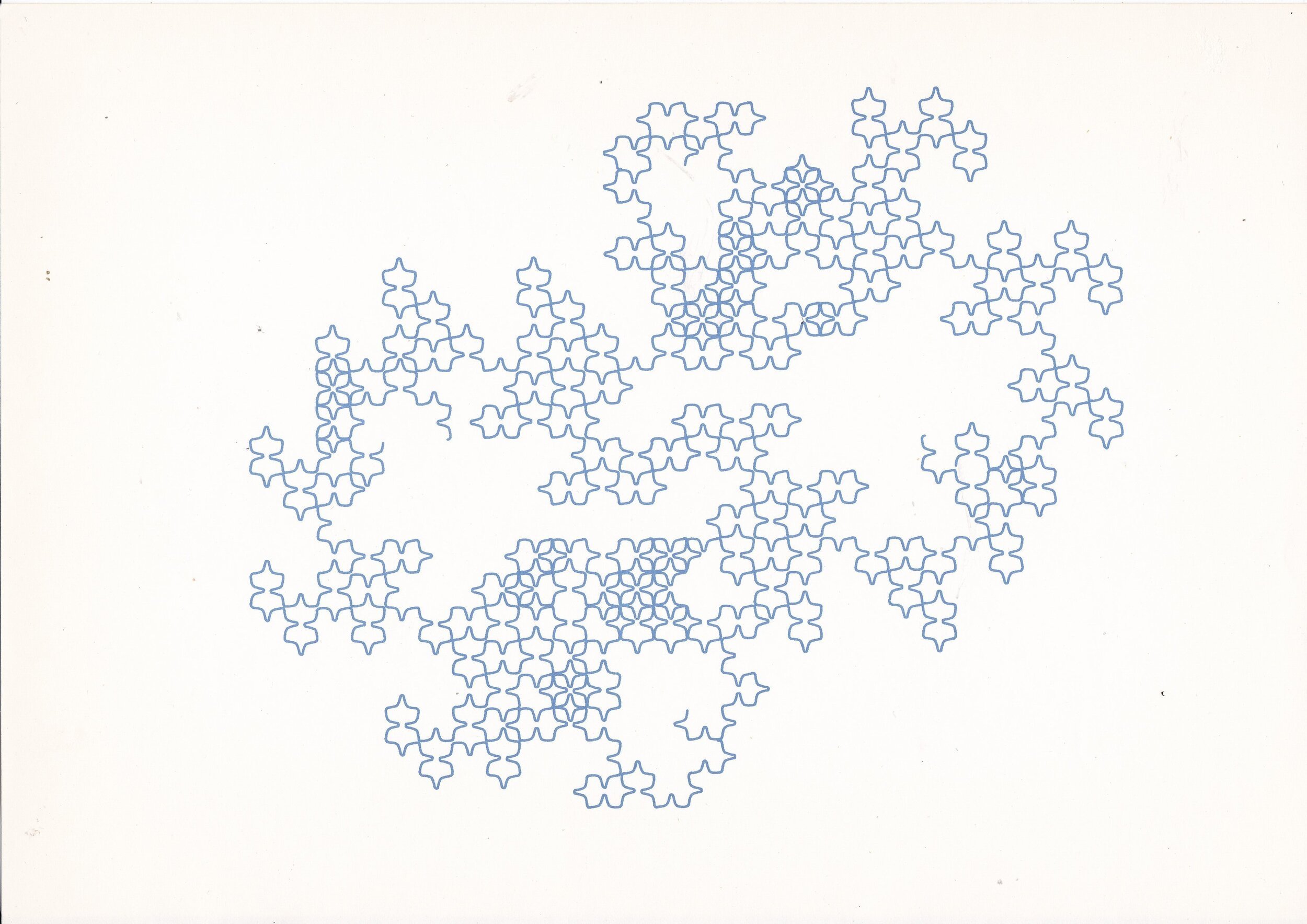

Vera Molnár

Vera Molnár is a Hungarian media artist living and working in Paris, who is considered one of the pioneers of computer and generative art. Early in her career, she was trained as a traditional artist at Budapest College of Fine Arts, then in 1947, she moved to Paris. In 1968, she began working with computers. She taught herself the early programming language Fortran, which allowed her to create algorithmic paintings with endless variations of simple geometric shapes. She gives instructions to the computer, which are outputted to a plotter drawing. She experiments with the transition between order and chaos, deliberately introducing a 1% disorder, a systematically defined factor of a chance to influence his works. She became a cofounder of several artistic research groups, such as G.R.A.V., which investigated mechanical and kinetic art, and Art et Informatique, which focused on art and computing. Her works have been featured in major solo and group exhibitions and in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Victoria and Alberts Museum, and the Centre Pompidou.

Charles Csuri

Besides Vera Molnár, Hungary can also boast another pioneer of computer art, Charles Csuri, who created new artistic tools for 3D computer graphics, computer animation, gaming, and 3D painting. He was born in 1922 in Grant Town, West Virginia, to parents from Hungary. Charles, also known as “Chuck”, was the team captain of the OSU national championship football team in 1942. Then, from 1943 to 1946, he fought for the US in the Battle of the Bulge, receiving the bronze star for heroism. After the war, he returned to Ohio State and completed his studies in art. He was the youngest professor with academic degrees in Fine Art, Engineering, and Computer Science. At the university, he established a series of graphics research centers.

He started experimenting with computer-based multimedia in the 1960s, in the form of plotters, canvas, screen print, sculptures, holograms, and animation. He was quickly recognized by museums such as MoMA or the Association for Computer Machinery Special Interest Group Graphics. After spearheading developments in the field of computer graphics, he created the first computer animation company, Cranston Csuri Productions, in 1984. Charles created digital art till the age of 99. At the end of his life, he was also experimenting with NFTs. He will be remembered as a renaissance man: an athlete, professor, artist, and innovator, who combined art and technology as one of the first pioneers of the genre.

Leslie Mezei

Leslie Mezei is one of the most influential participants in the North American computer art scene. He was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1931. In the 1940s, he emigrated to Canada as a war orphan and holocaust survivor. In the 1950s, he started studying physics and mathematics at McGill University, Montreal, then he moved to Toronto, where he obtained a master’s degree at the University of Toronto. He stayed at the university, first as an assistant and then as a professor from 1964 to 1978.

His experimentation with computer art started in the 1960s. He developed two early graphic programming systems, SPARTA and ARTA, featuring graphic primitives and transformations like lines, polygons, rotation, and random number generators. The ARTA enabled the use of a light pen as an input device as well as keyframe animation. From 1968 he collaborated with Frieder Nake, Bill Buston, and Ron Baecker, whom he had invited to Toronto for a project called “Dynamic Graphics”. In the late 1970s, he turned away from computer art and began working as a personal financial planner and writing about spirituality.

"The Inner World" series by Dominikus will launch on Art Blocks on the 2nd of September

What is bigger, the inner space or the outer? - Dominikus asks this question in his latest series, ‘The Inner World”, which consists of 400 works and will launch on Art Blocks on the 2nd of September.

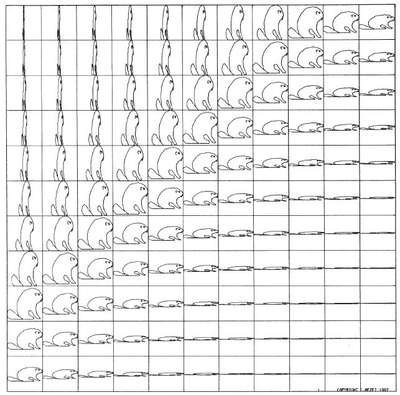

The Inner World #99, (sample outputs) by Dominikus / Copyright © Dominikus

This project was inspired by the multitudes we keep within us. The harsh shadows and the combination of pure 2d rendering with a 3d effect mimic feelings of separation from the rest of the world. Their undetermined scale reflects the seemingly unlimited depths of consciousness.

The Inner World starts its rendering from one or more circular cores representing the centers of our personalities. Each of these cores spawns various thoughts and emotions, flowing as tendrils through the scene, making connections among themselves or reaching for the outside. Their movement ranges from straight and orderly to (seemingly) chaotic, sometimes twisting the clean underlying personality center into a completely different shape. Two rendering styles (illustrative and shaded) with palettes ranging from cool, gloomy, and serious to cheerful or dramatic reflect the variety of predispositions.

While waiting for the rendering to complete, look at the focus animation highlighting the circular cores of your piece. You're invited to spend this time pondering how everything you know, everything you have or will ever experience, and even the most majestic sights from stars to microbes fit into the space between your ears.

The whole series will be available on Art Blocks.

Dominikus's unique works can be found on his Foundation page and the PHYGITAL website.

His works will be on display on OnCyber between the 2nd - 9th of September.

The co-founder of Ars Electronica, Herbert W. Franke passed away at the age of 95

"Art is always about mathematics. Every image can be described mathematically. There is nothing more than a formula behind it.”

One of the pioneers of generative art has died: Herbert W. Franke, artist, writer, physicist, and philosopher, whose work influenced generations of new media artists, was 95 years old. Herbert's death on the 16th of July was announced by his wife, Susanne.

Herbert Werner Franke Image © the artist

Herbert Werner Franke was born in Austria on May 14, 1927. He studied Physics and Philosophy in Vienna. In 1951 he received his Doctorate in Theoretical Physics by writing his dissertation about electron optics. Today Franke is known as the most important post-war German-language writer in the genre of science fiction. Franke is also recognized worldwide as a pioneer of algorithmic art. His intellectual work is based equally on the rationality of the researcher and the creativity of the artist. He is particularly interested in creating aesthetically interesting structures with the help of computer programs. In addition to creating works of art, Franke has also been intensively involved in questions of rational aesthetics. In his "Rational Theory of Art," published as early as the mid-1960s, he described the perception of art as a construct that can be grasped with the help of information theory.

Kate Vass Galerie is honored to have worked with him and exhibited his works. He was part of our AUTOMAT UND MENSCH exhibition in 2019, where we put important work by generative artists spanning the last 70 years into context by showing it in a single location. By displaying important works like the 1956/’57 oscillograms by Herbert W. Franke, we showed the full history and spectrum of generative art.

The MATH GOES ART was a solo exhibition in 2021 at Kate Vass Galerie, that was dedicated to Herbert's latest period, the so-called Math Art. Herbert W. Franke has been interested in mathematical aesthetics for the last decades and had experimented with algorithms and computer programs to visualize math in art.

"It opened my eyes to things I had never seen before, such as beautiful crystalline landscapes. It soon became clear that if the electric fields were deliberately calculated differently, quite adventurous figures would emerge. That gave me the idea of using other tools of technical laboratories, such as oscillographs and later computers, to create images for artistic purposes." - he commented.

Drakula Series, 1970 - 1971

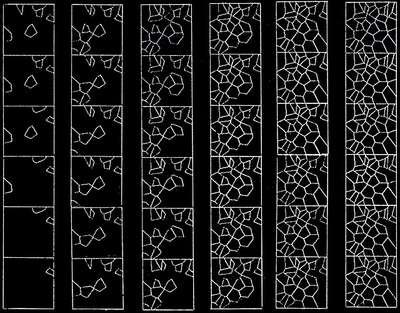

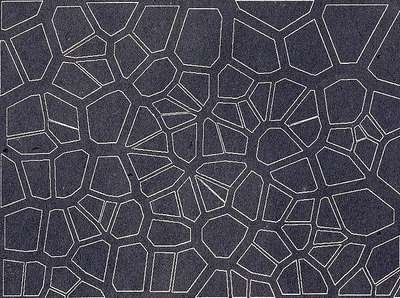

The Drakula series, from the seventies, was displayed at the MATH GOES ART show. The series was an ideal instrument as a study object of experimental aesthetics since they could be quantified well in terms of information theory. The Heighway dragon curve was first discovered by NASA physicists John Heighway and Bruce Banks in 1966 and named by his colleague William Harter. It can be constructed from a base line segment by repeatedly replacing each segment by two segments with a right angle and with a rotation of 45° alternatively to the right and to the left. Franke's 'dragon curves' are formed by sequences of left and right turns according to certain rules. The program allows to string together and superimpose dragon curves of different orders - or even sections of such curves.

The Lissajous Series

We are also proud that Herbert minted his first NFTs with the Gallery. The Lissajous series consists of 11 works in two color combinations: Lissajous blue/orange and Lissajous pink/turquoise. Only 4 were minted on opensea.io and are now only available from the secondary market. The Lissajous figures can be defined as any of an infinite variety of curves formed by combining two mutually perpendicular simple harmonic motions, commonly exhibited by the oscilloscope, and used in studying frequency, amplitude, and phase relations of harmonic variables. They are named after the French physicist Jules Antoine Lissajous (1822-1880). Lissajous curves are sometimes also known as Bowditch curves after Nathaniel Bowditch, who studied them in 1815 but were studied in more detail by Jules-Antoine in 1857.

Two artworks of Herbert W. Franke are currently available at Phillips Auction. More information can be found here.

The artists, Robbie Barrat, Mario Klingemann, Herbert W. Franke and co-curators Jason Bailey and Georg Bak with Kate Vass, at Kate Vass Galerie 2019 Automat und Mensch

Ex-Machina: A History of Generative Art by Phillips

Ex-Machina: A History of Generative Art © Phillips