The Father of Computer Art: The Art of Charles Csuri

Charles Csuri, Image © the artist

Charles Csuri (1922-2022) is known as “The Father of Computer Art”. He was a professor, fine artist, and computer scientist who made significant contributions to the field of computer art. Through his research and artistic vision, Csuri developed software that created new artistic tools for 3D computer graphics, computer animation, gaming, and 3d printing.

Charles Csuri was born in 1922 in Grant Town, West Virginia, to immigrant parents from Hungary. He afforded college with a football scholarship in 1942 to The Ohio State University. After attaining The Bronze Star for heroism in WWII at “The Battle of The Bulge” he continued his education with the GI bill. Further, in 1943 the US Army sent him to the Newark College of Engineering, where he studied algebra, trigonometry, analytic geometry, calculus, physics, and chemistry, and received a degree in engineering. After the war, Csuri turned down an opportunity as an All American O.S.U. football player to join the NFL. Instead, he received his MFA in classical art education studying painting, drawing, and sculpture alongside his close friend Roy Lichtenstein in the 1940s. In 1947 Csuri became a professor teaching fine art while exhibiting his paintings in N.Y. During this time, he created traditional paintings, drawings, and sculptures but had a continuing dialogue with a friend and engineer at The Ohio State University in the early 1950s about working with the computer to create art. The problem seemed like science fiction till 1964 when he saw a raster image made using a computer. In the same year, he took a course on computer programming and created his first computer-generated picture in 1964 with an analogue computer and in 1965 an IBM 7094 with a drum plotter using FORTRAN programming language. In addition to teaching fine art, Csuri became a professor of Computer Information Science and created digital art with custom software in a Unix environment.

In 1968, Csuri sent shockwaves through the University by being the first artist to receive financial support from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Csuri used this funding to support computer scientists in a collaborative effort to develop the artist's tools he envisioned to create computer art. He implemented a three-part program: building up a library of data and programs that focused on creating new artistic tools for the generation and transformation of images, developing a graphic console, and establishing an educational program. With the grant, he proposed a formal organization, called the Computer Graphics Research Group (CGRG) at OSU in 1971, which he later renamed to Advanced Computer Center for the Arts and Design (ACCAD), in order to develop and experiment with the potential of the application of computer animation. NSF was so impressed with his work, that they supported his creative research for twenty years. The results of this research have been applied to a variety of fields, including flight simulators, computer-aided design, visualization of scientific phenomena, magnetic resonance imaging, education for the deaf, architecture, and special effects for television and films. In 1984, Csuri established the first computer animation company in the world, Cranston Csuri Productions, which produced animation for all three major U.S. television networks, the BBC, and commercial clients.

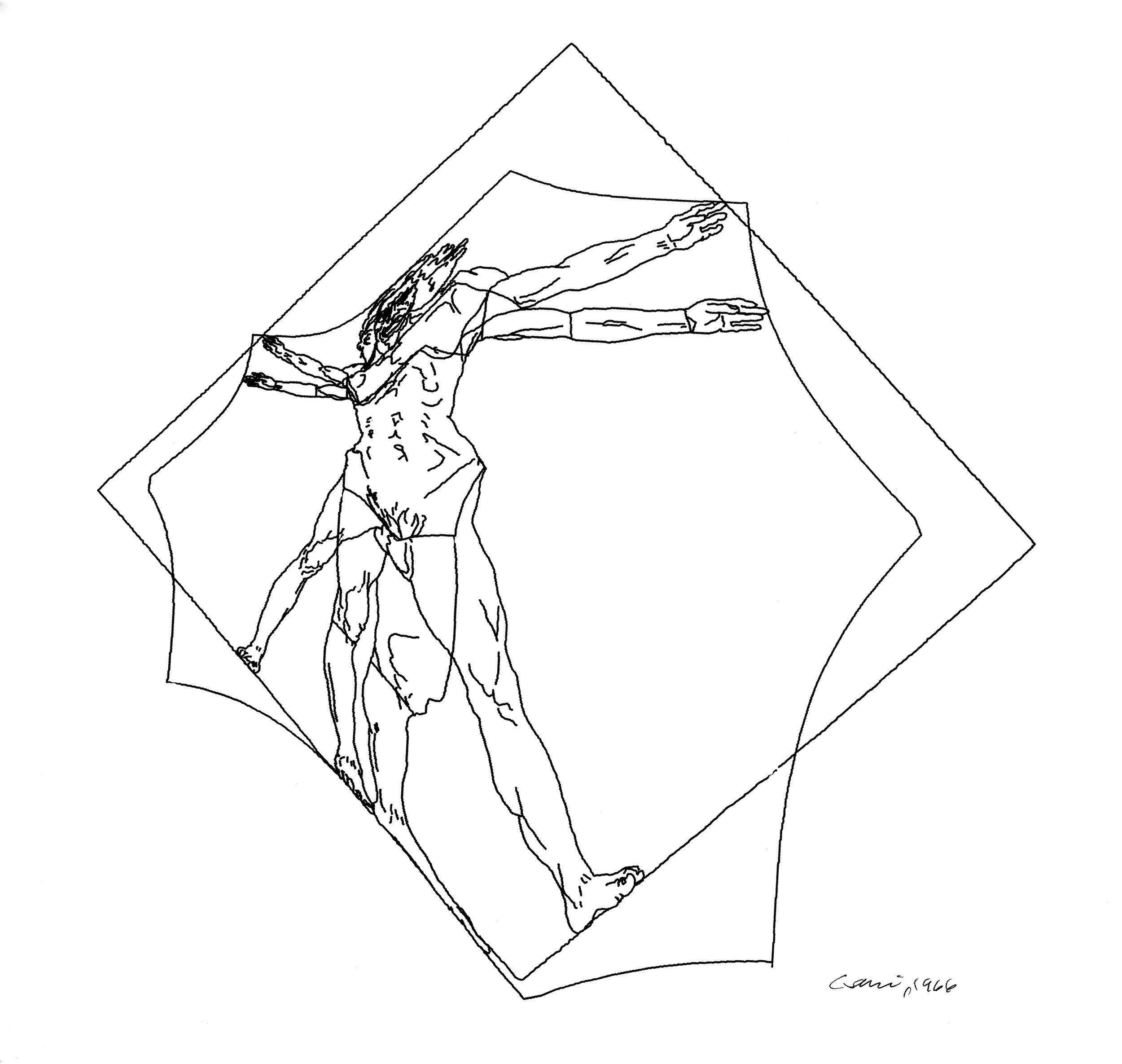

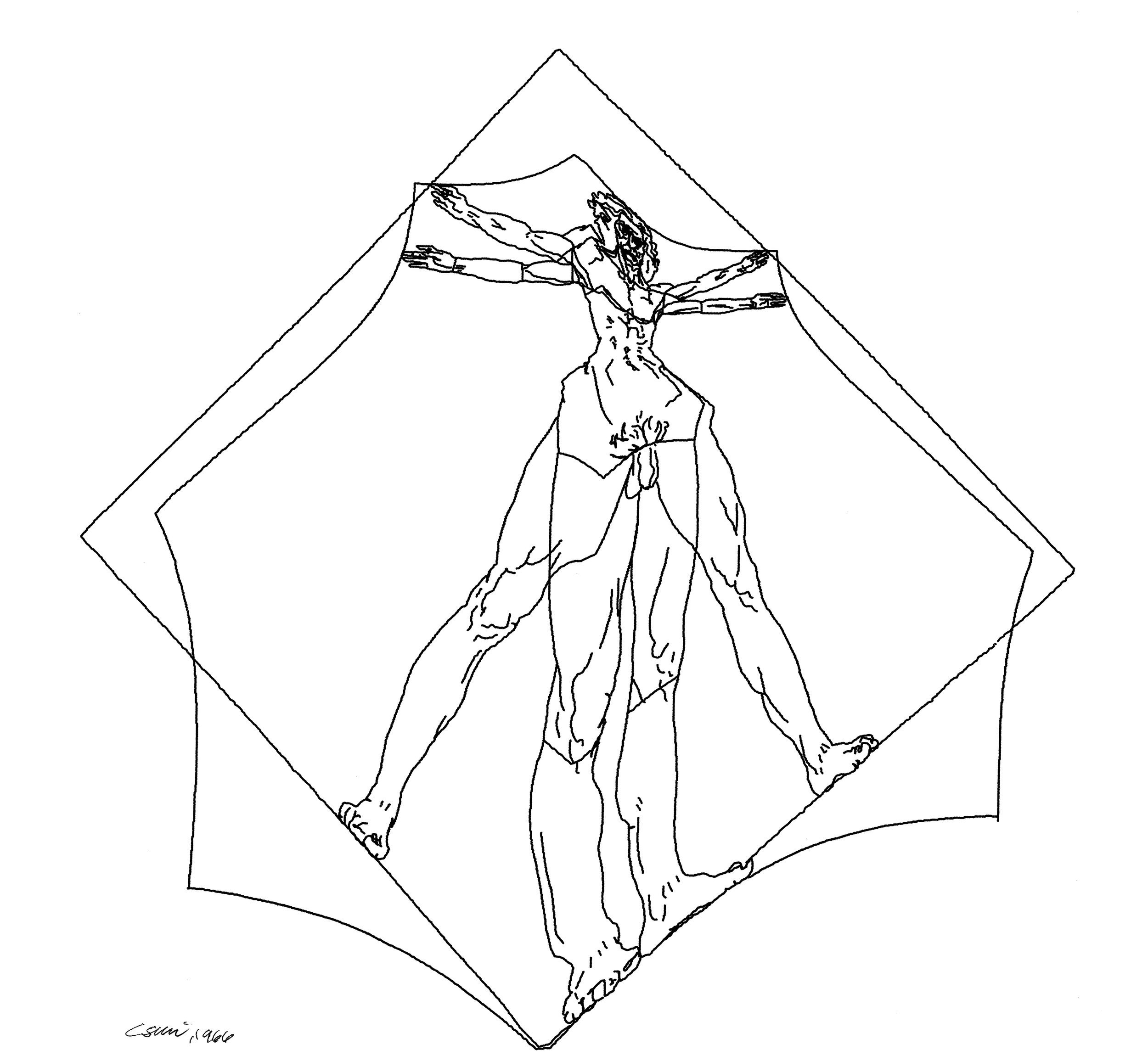

EARLY PERIOD (1963 - 1974)

His early works, from mid-1963 to the 1970s are significant. His way of thinking about computer art, his creative process, and his intentions during this period helped shape his later art. Many of the themes, such as object transformation, hierarchical levels of control, and randomness were established in the early years. In the early days of his career, Csuri's art consisted of his drawings and sketches, which he made in order to mathematically transform them using analogue and digital technologies. In 1968 Csuri made an important discovery by creating a numeric milling machine sculpture as the brainchild for his pioneering development in the next phase of his career. In the early 1970’s he took this visionary idea further to develop 3D animation and real-time interactive art objects.

One of the best examples of his early period is the Hummingbird (1967), which is considered to be one of the earliest computer-animated films. To create the film, he generated over 30.000 images with 25+ different motion sequences using computer punch cards. The output was then drawn directly onto the film using a microfilm plotter. The resulting animation shows a hummingbird dissolving, recomposing, and floating along imaginary waves. The film received an award at the Fourth International Experimental Film Competition in Brussels, then MoMA in New York purchased it in 1967 for its permanent collection as one of the first computer animations.

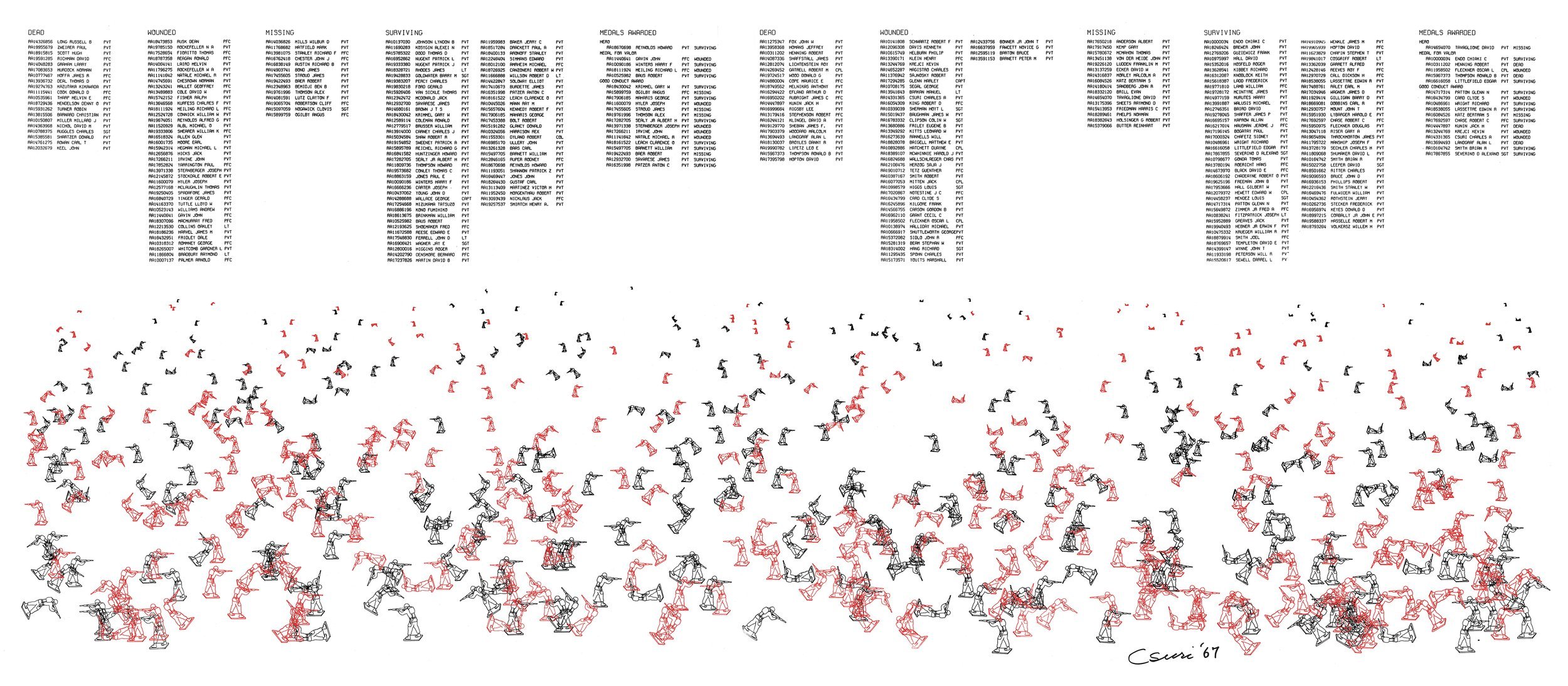

Csuri’s interest in randomness and game-like playfulness is exemplified in work, Random War (1967). In his work, he gave pictures of 400 soldiers along with a written list of their names to the computer. Using a pseudorandom number generator, the computer determined the distribution of the soldiers on the battlefield. The names became the soldiers under the categories of “Missing in Action”, “Wounded”, “Dead”, and “Medals Awarded”. Csuri used the soldiers’ names to personalize the randomness and chaos of war. Csuri also used pop icon names as well as presidents, and ordinary people to emphasize that war in life and death doesn't discriminate. This was an important conceptual and ironic commentary on the computer playing GOD in an age when computers were considered evil. For Csuri as a veteran, this artwork was pivotal in his search for meaning in his life-spanning digital artistic career.

MIDDLE PERIOD (1989-2000)

In 1990, Csuri became a professor Emeritus, retiring from his role at ACCAD to focus on creating digital art. During this middle period, he started experimenting with combining traditional drawings and paintings with evolving proprietary software developments. He brought his drawings into a three-dimensional computer space and used techniques like texture, bump mapping, and embossing.

Csuri describes his works as “organic looking”, suggesting that the use of traditional media helped to remove the sterile feeling of the mechanical computer forms. Developing the technique called texture mapping, he wrapped the virtual models with his oil paintings. The result is playful and focuses on the beauty and elegance of life.

A good example of this period is A Childs's Face. Csuri created a thick application of oil paint, that he wrapped around the computer-generated bust head that appears to be emerging from the background. Csuri plays with positive and negative space in a strong mix of pattern, color, and three-dimensional texture. Csuri also applies this technique with his drawing in The Hungarians.

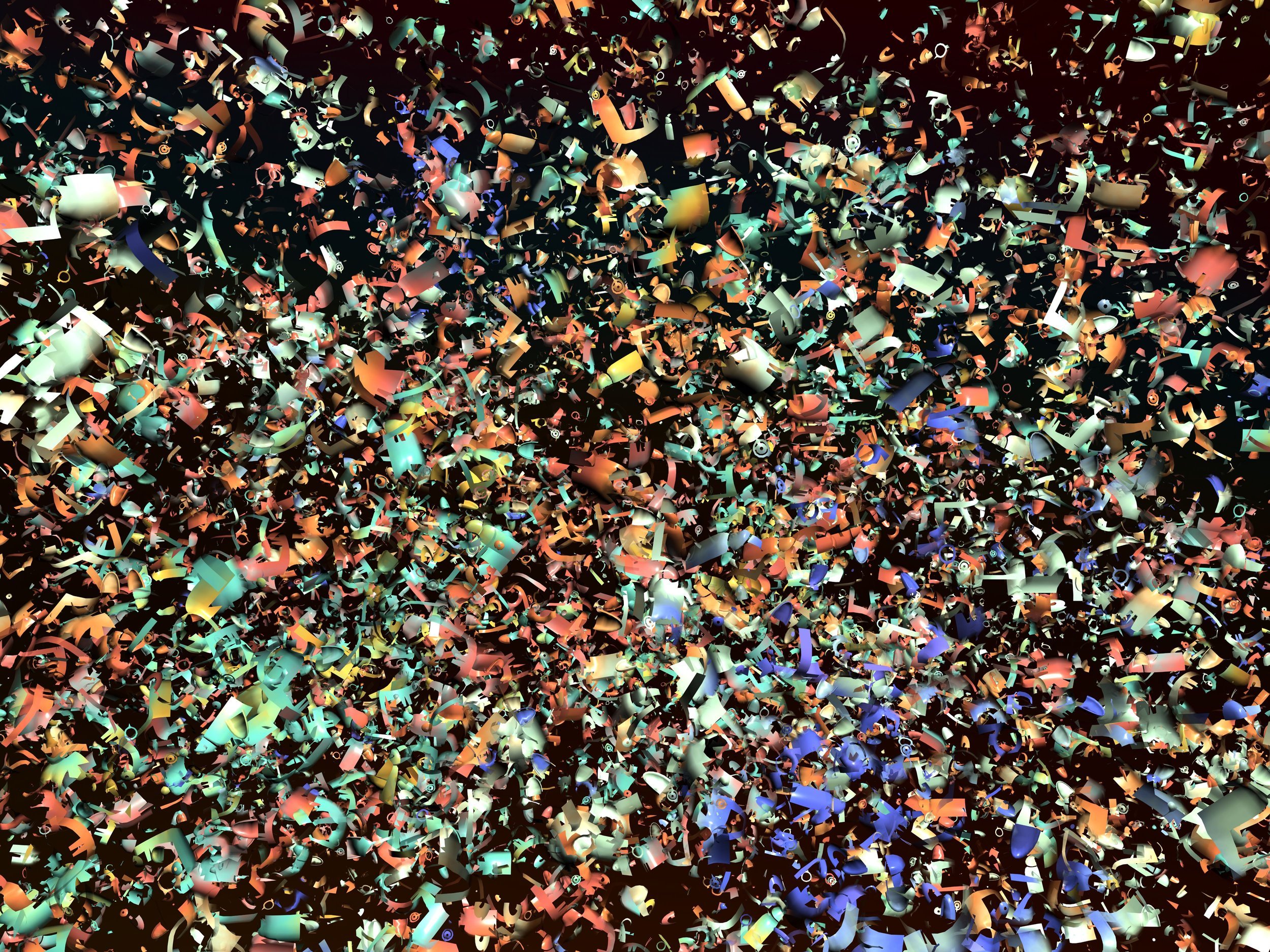

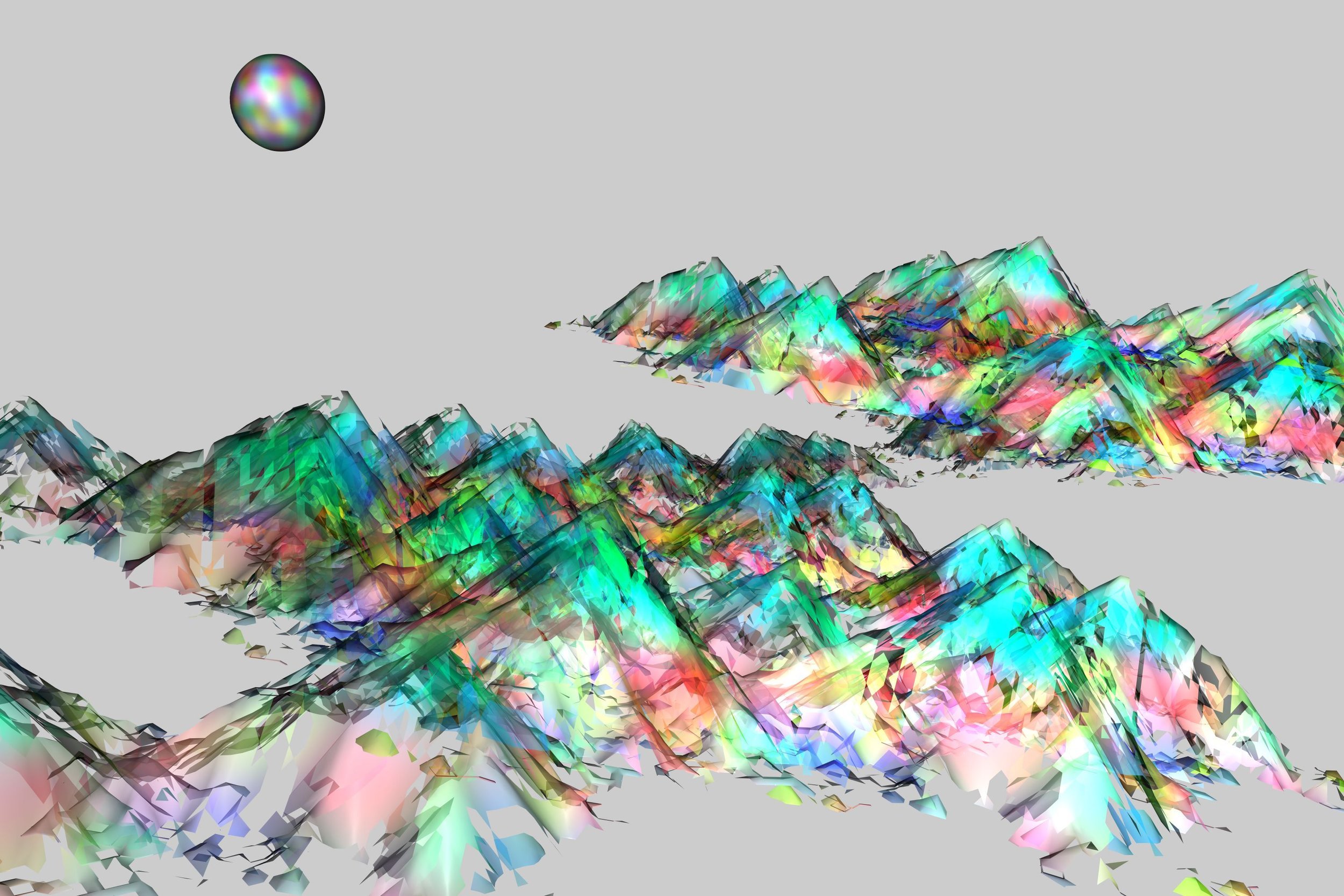

During this period, he continued to define artistic tools in collaboration with computer programmers through the development of custom software programs. Some of his core programming tools were the ribbon tool, the fragmentation tool, and the colormix tool. The fragmentation tool gave Csuri the ability to play with abstraction and representation. In the work, Cosmic Matter, Csuri fragmented digital models of classical sculpture where he simulated paint flying in the solar system.

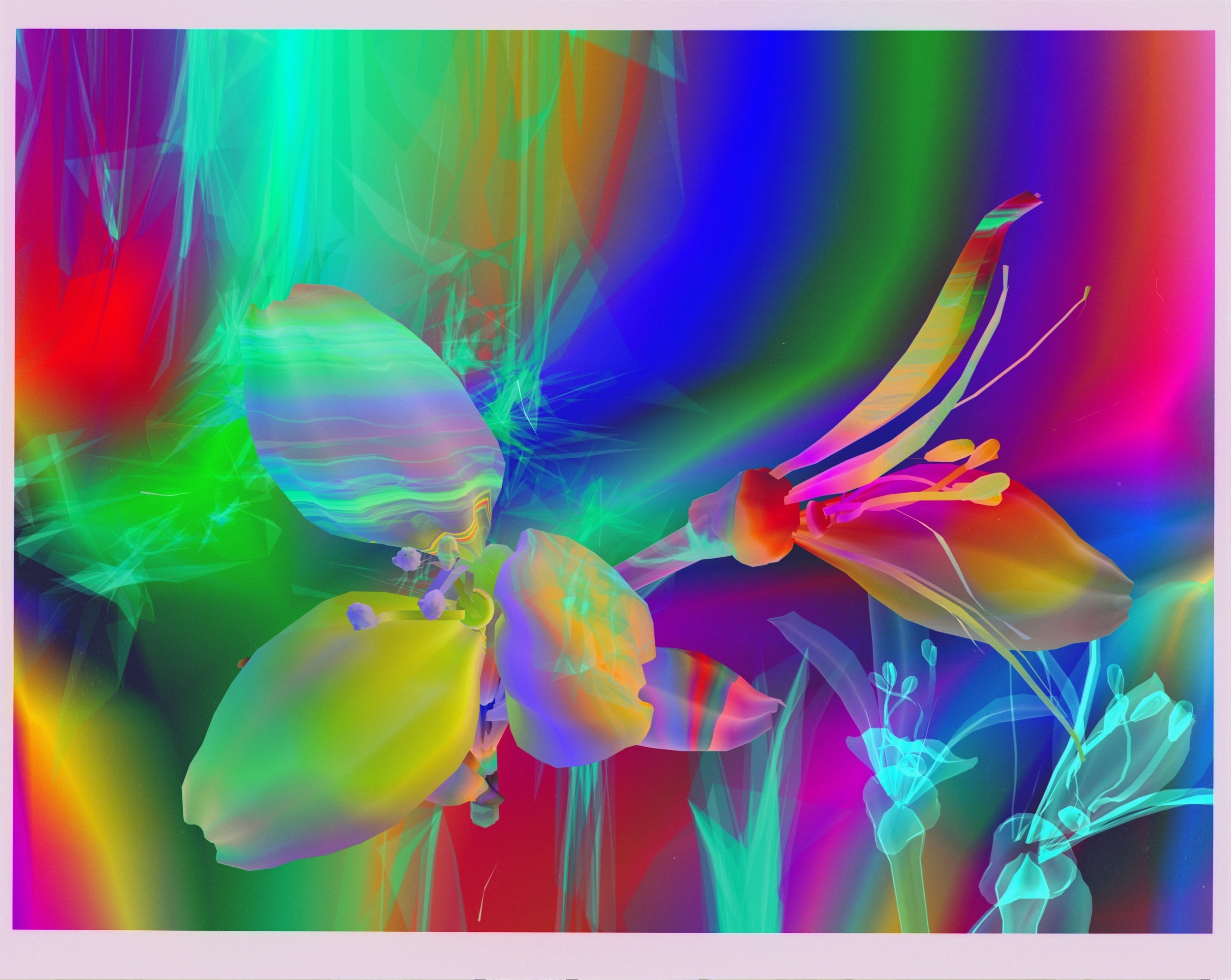

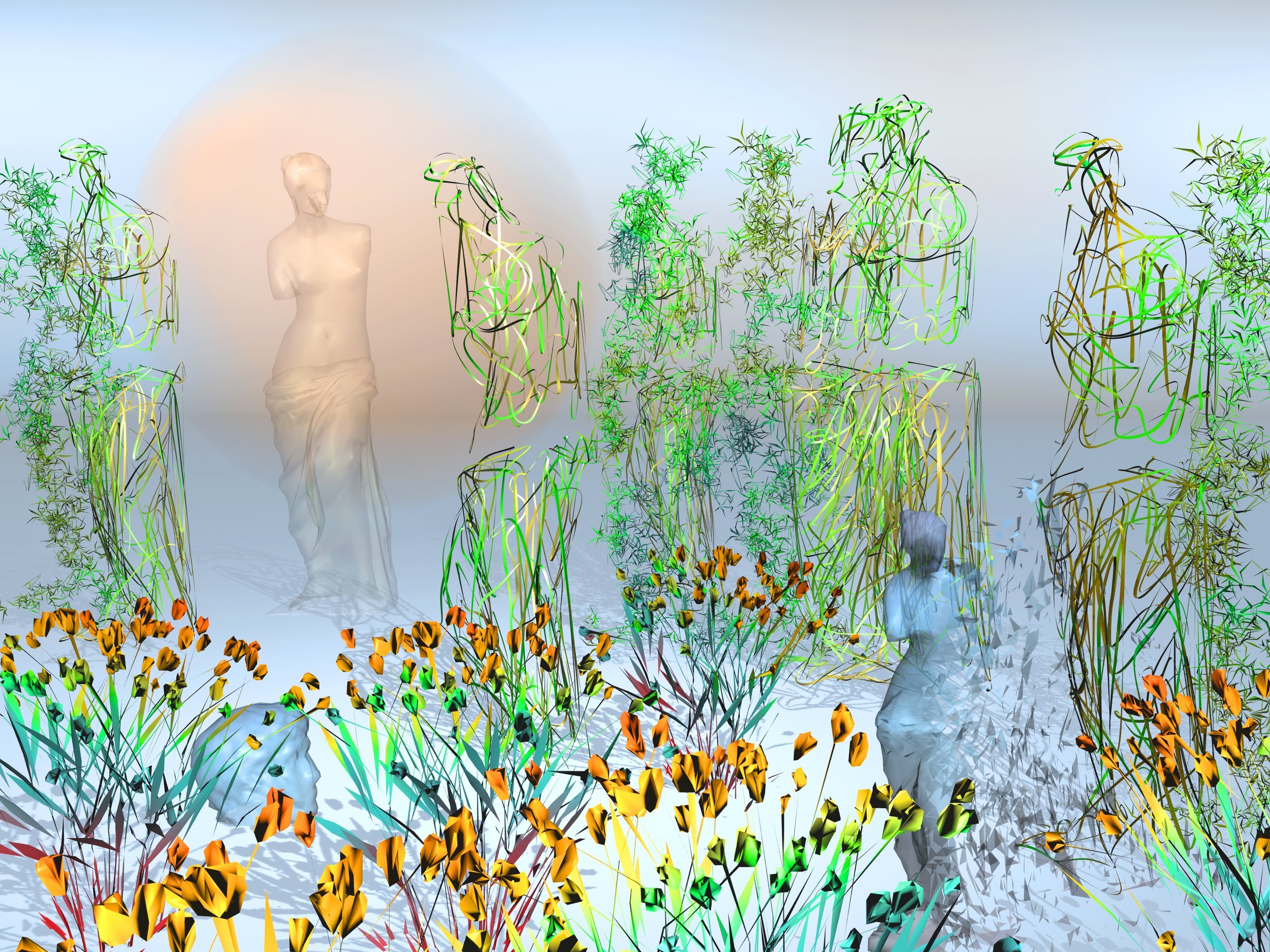

The colormix tool allowed him to define the location of specific colors and create color spaces through which Csuri can place or move his objects. In Wonderous Spring, he used prismatic colors in a transparent layering of forms.

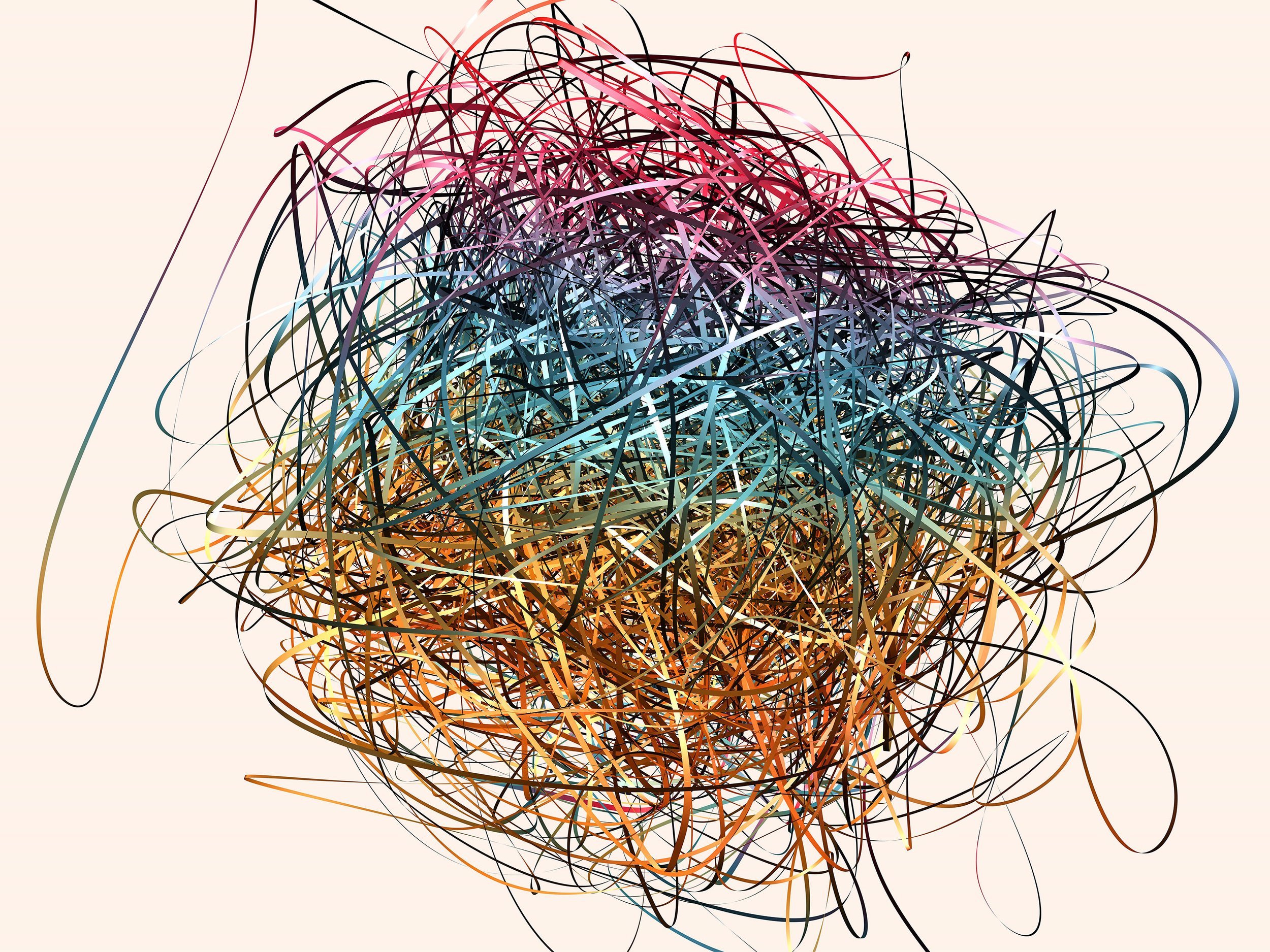

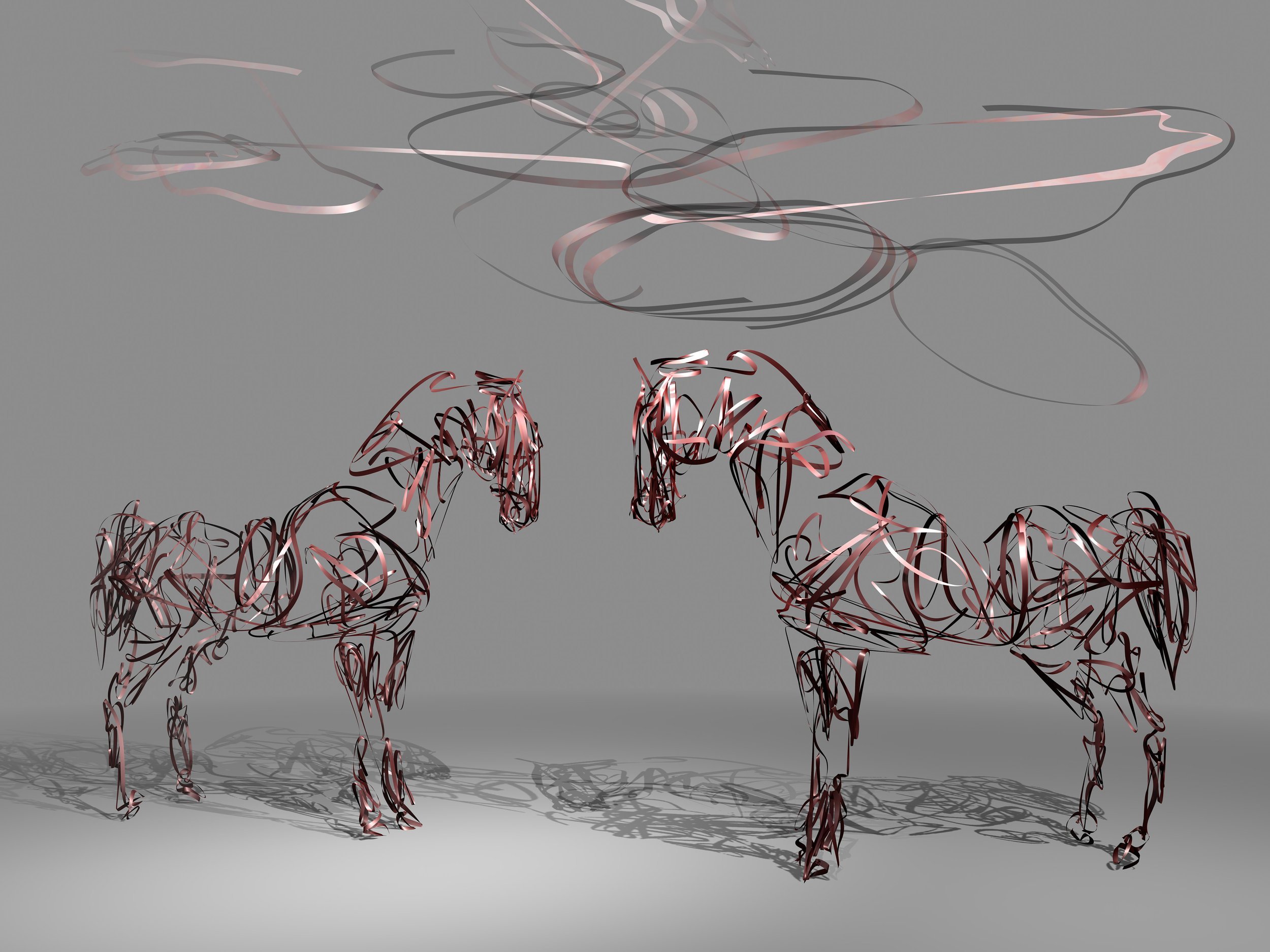

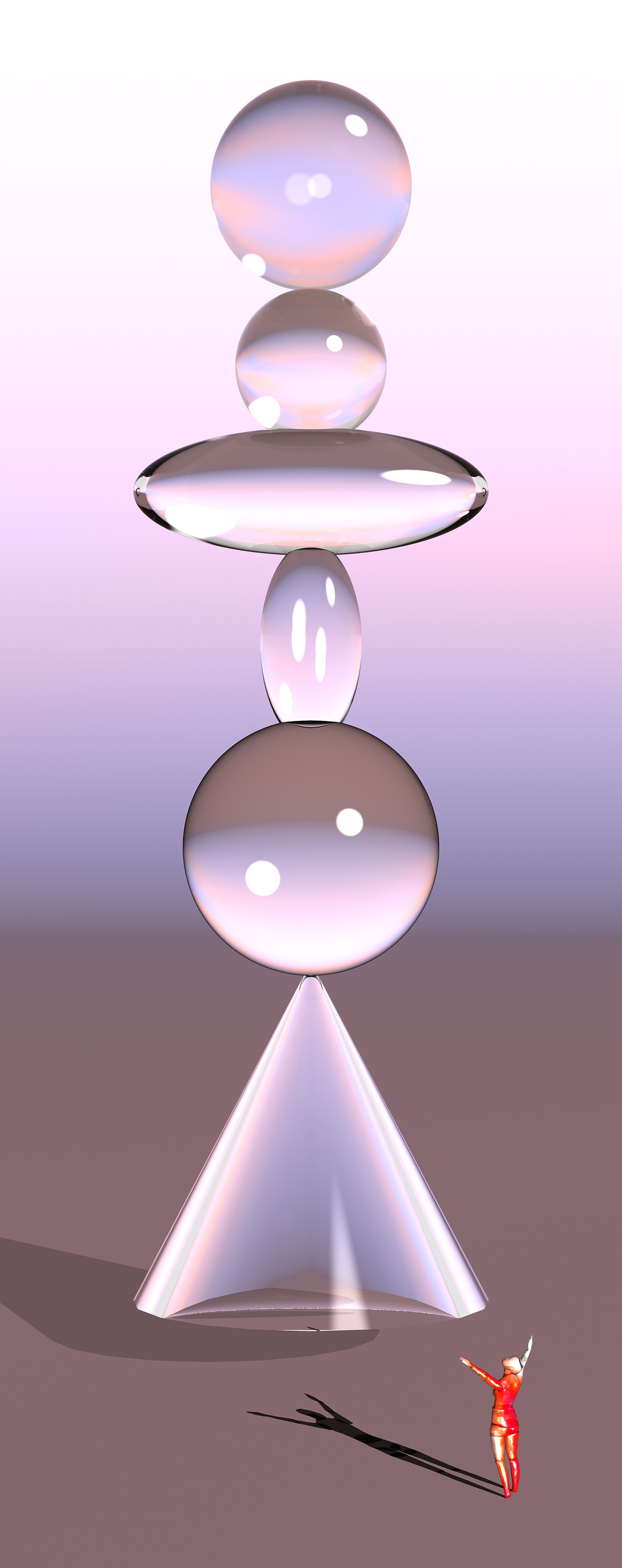

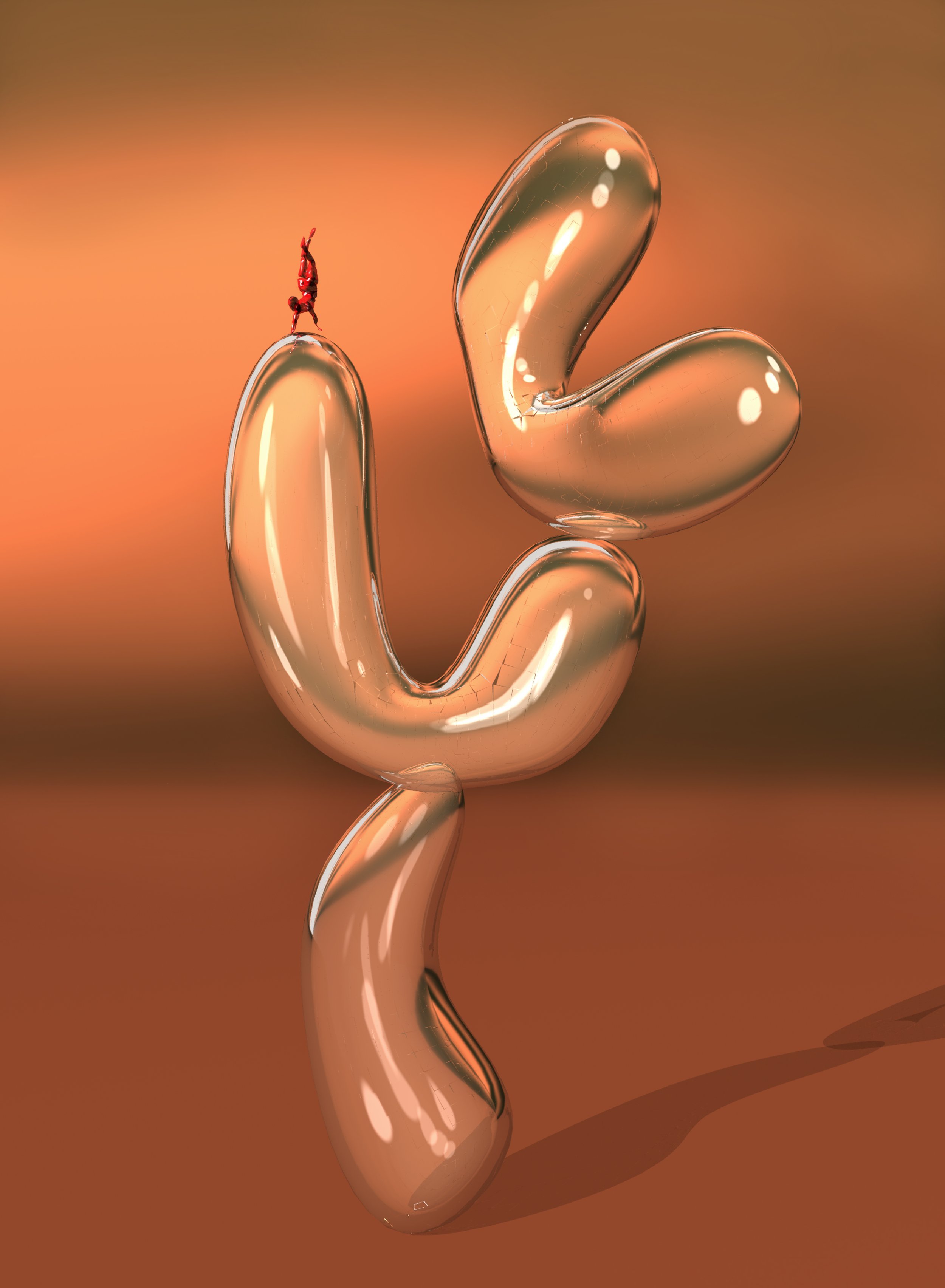

Csuri wanted to “draw” in 3 dimensions so he spearheaded the development of a ribbon tool that appears to draw calligraphic lines in the three-dimensional space. Csuri has used this tool to create works, such as Wire Ball and Horseplay. Another of his digital developments during this period was his experimentation with the interplay of light and transparency. His artistic vision was to create a reflective glass-like quality in 3D layers of transparency and objects. Balancing Act and Clearly Impressive

LATER PERIOD (1996-2006)

In his later period, Csuri uses the core artistic tools, which he created in the early 1990s and he continually modified them throughout his artistic career. One example was the implementation of his fragmentation tool to later apply to millions of objects in a random generative process. Csuri often functioned as an artistic editor while striving to uniquely create by computer something that could never be accomplished by hand. Celestial Clutter, Mosaic Lines, Festive Frame, and Abstract Ribbons. Nevertheless, the influence of the history of art and great masters continues to be an important part of his creative ambitions.

The father of modern art, Paul Cézanne had a significant influence on Csuri’s work and philosophy. Cézanne uses simplified geometric forms of the sphere, cylinder, and cone, forming them with light and color, composing a new order that transforms the visual language of art. Csuri spent years studying Cézanne's methods of manipulating color and light. He also redefines the objects in a three-dimensional space in which he creates new forms that synthesize realism and abstraction. Csuri further was influenced by the artwork of Leonardo Da Vinci and named many of his files Leo. As early as 1966, Csuri created The Leonardo Da Vinci Series with an IBM 7094 and drum plotter he transformed The Vitruvian Man by computer. He was inspired by concepts like Chiaroscuro and Sfumato as seen in Light_0008. where the smoky quality blurs contours so shapes emerge in an atmospheric quality. Reference to Cezanne's color in Landscape Two.

In Venus in the Garden Frame 73, from the Venus series, Csuri uses the famous Greek sculpture of Venus de Milo with his artistic set of parameters that control light, color, transparency, objects, camera position, and distances in a generative process. Here Csuri explores the mysteries of ancient myths and the evolution of organic forms. The sculpture is embedded in repeating and juxtaposed decorative motifs of ribbons, leaves, and flowers that blur the line between the figurative and the abstract. The interplay of elements in this algorithmic painting creates a rhythmic balance in an organic composition.

Origami Flowers is another example of the influence of traditional art history in Csuri’s art. The clump of irises is a reference to Csuri’s admiration for Japanese art and Van Gogh’s Irises. The work is a mathematical object constructed from polygons, in three-dimensional space with a light source placed by the artist. It consists of a complexity of shapes and lines, the intensities of light and dark colors, and the spatial depth resulting from multiple overlaps of material.

In the 1960s, Charles Csuri began exploring the use of randomness and chance in his art, as seen in works such as "Random War" and "Feeding Time." In the 1990s, he returned to this interest and created a series of generative art pieces known as the Infinity series. These works were generated using computer algorithms and mathematical equations, resulting in unique, endlessly repeating pieces. Csuri created three-dimensional environments composed of geometric forms, colors, lights, and shadows, assembled from thousands of fragmented objects. The overarching theme throughout his career has been in search of artistic and conceptual meaning in every creation by image transformation.

Charles Csuri continued creating digital art and animation until the age of 99. He is recognized as a true renaissance man: an athlete, professor, artist, and revolutionary innovator who combined art, science, and technology as one of the first pioneers of the genre. As an inspiring visionary, he mentored 60 PHD digital art and programming students. They have and will continue his legacy as a pioneer in the field of digital art and animation. Charles Csuri will be remembered in the history of art as a founder of the digital art movement. His revolutionary pictures and animation have been showcased in international exhibitions. His artwork can be found in renowned museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art NYC, Pompidou Center Paris, Victoria Albert Museum of Art London, and ZKM Museum Karlsruhe. LACMA Los Angeles, California. Whitney Museum of Art NYC, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb Croatia

Browse the works of Charles Csuri HERE!