HISTORY OF GENERATIVE ART - Generative Music

Aaron Penne and Boreta, Rituals - Venice #874 & #384, 2021, Source: ritualsalbum.xyz

In today’s History of Generative Art series, we explore a fascinating genre, generative music. Unlike traditional composition, generative music is created through algorithmic or rule-based systems that enable continuous variation and non-repetitive structures. Its development has closely followed technological advancements, from early computer music experiments to contemporary AI-generated works.

The tables of Wolfgang Mozart's 'Musikalisches Würfelspiel’, Source: ai.gopubby.com

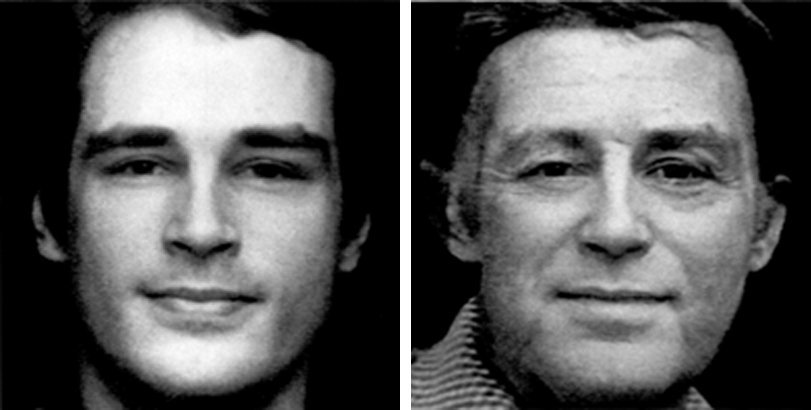

Max Mathews, Pioneer in Making Computer Music, Source: nytimes.com

The idea of musical randomization dates back to the 18th century with the Musikalisches Würfelspiel, which allowed composers to create pieces by rolling dice. As technology advanced, music’s mathematical nature made it ideal for computational approaches. Unlike visual media, audio data requires significantly less computational power, enabling digital manipulation well before real-time video processing became feasible.

The first breakthrough came in 1956, when Max V. Mathews developed MUSIC I, the first digital audio synthesis program at Bell Laboratories. In the 1980s and 1990s, David Cope created Experiments in Musical Intelligence (EMI), a system that analyzed and recomposed music in the styles of Bach, Mozart, and Rachmaninov. The results were so convincing that some listeners mistook them for human compositions.

Lejaren Hiller at the Experimental Music Studio, Source: burchfieldpenney.org

While scientists were developing computational approaches, several composers had already begun experimenting with algorithmic and self-generating musical processes. Lejaren Hiller composed the “Illiac Suite” (1957), the first complete work generated by a computer algorithm, using stochastic methods and rule-based selection.

The term “generative music” was popularized by Brian Eno in 1995, when he collaborated with SSEYO’s Koan software to create music that continuously evolved based on predefined rules. Eno described this genre as an ever-changing system rather than a fixed composition. His 1996 release “Generative Music 1” demonstrated these principles, by showcasing tracks generated using the software. In 2024, a documentary about him, Eno, was released, following a similar approach, it uniquely re-edits itself for each screening. Trailer.

Brian Eno, Generative Music 1, 1996, Source: progarchives.com

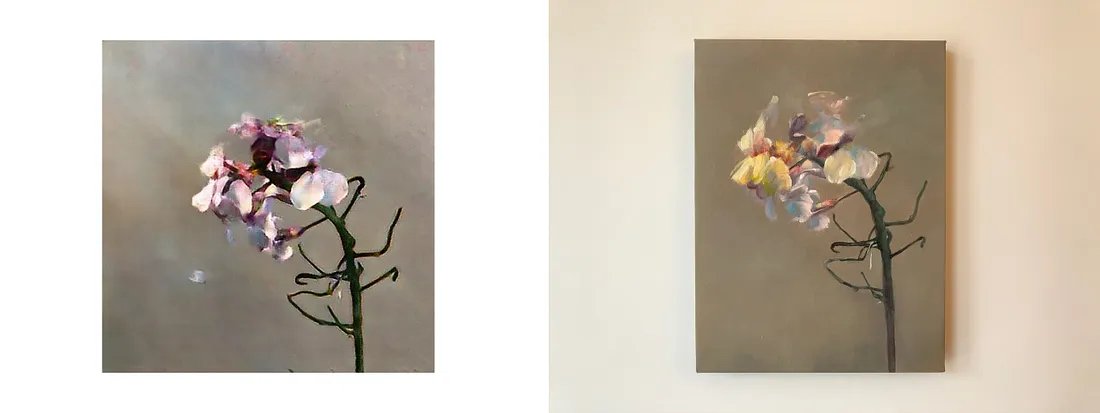

Artists now use programming languages and algorithms to create rule-based systems, sometimes combining their generative visuals with generative sound. “Rituals – Venice” (2021) is an audiovisual work that merges Aaron Penne's visuals with Boreta's meditative music. The calming, immersive experience was released on Art Blocks. Its code generates a continuous, non-repeating output for over 9 million years.

AI has also influenced generative music. Deep learning techniques, such as those used in DeepMind WaveNet (2016), have enabled realistic neural synthesis of sound. In 2023, Patten released “Mirage FM”, one of the first full-length albums composed entirely with Riffusion, a new advanced technology. The album transforms written descriptions into dreamlike compositions that blend pop, techno, hip-hop, R&B, and ambient.

AI and blockchain have enabled new methods of composition, distribution, and interaction in generative music. While the field faces challenges in areas such as creative control, authorship, and long-term viability, the genre remains a subject of study and experimentation in both artistic and technological contexts.

COLLECTOR’S CHOICE - Mistaken Identity by Mario Klingemann

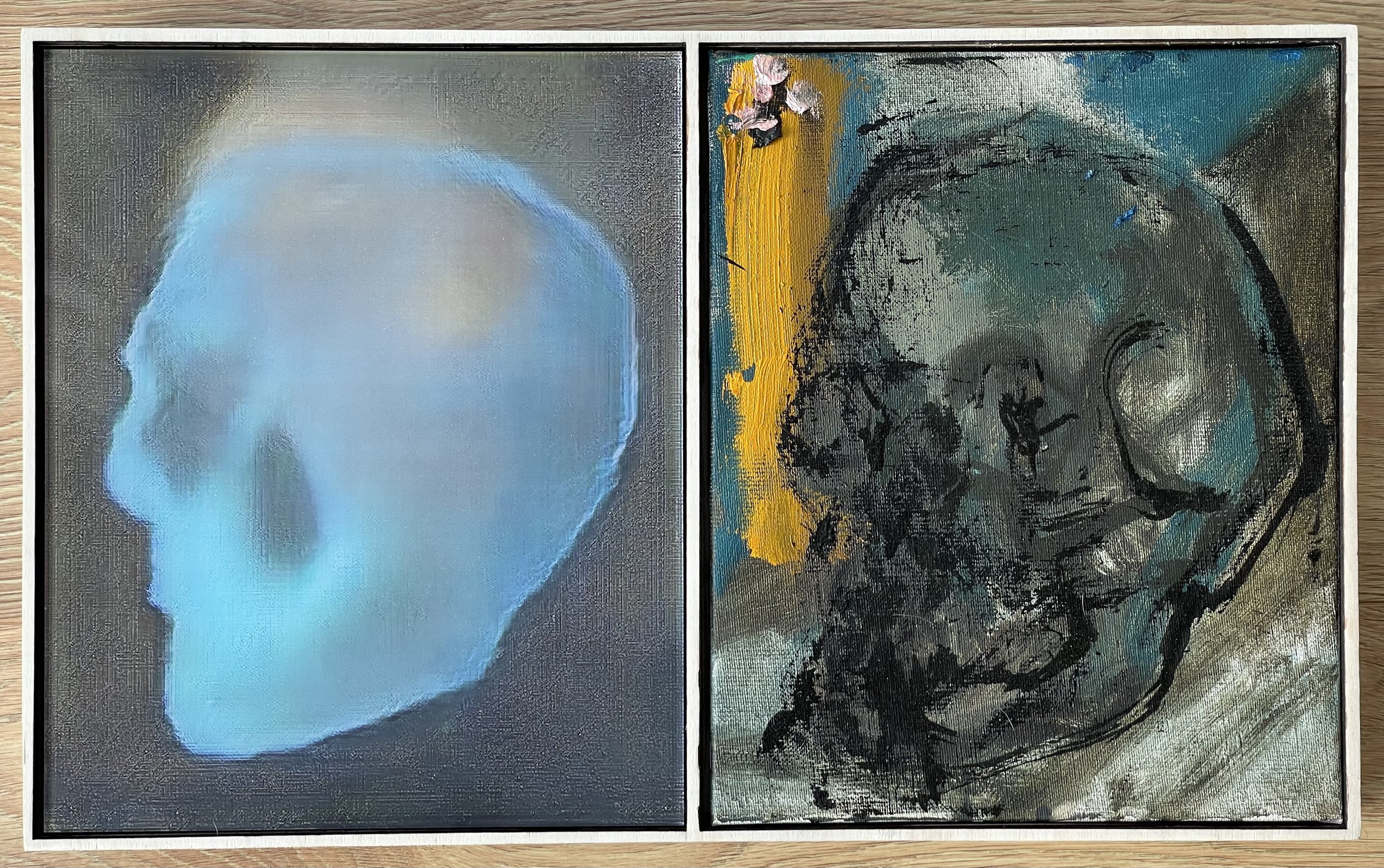

Mistaken Identity by Mario Klingemann represents a complex exploration of neural networks through the deliberate manipulation of their internal structures. This work consists of three videos created using generative adversarial networks (GANs) and neural networks. Exhibited at the ZKM in Karlsruhe during the Beyond Festival in October 2018, the triptych investigates how neural networks interpret visual information.

Mario Klingemann, Mistaken Identity, 2018, a video triptych

Mario Klingemann is known for his pioneering work in generative and AI art, with preferred tools including neural networks, code, and algorithms. His artistic practice reflects a systematic approach and curiosity about understanding complex systems. Klingemann often dissects systems such as neural networks, analyzes their components, and reconstructs them to explore patterns and to recreate and understand the system’s behaviors.

Portrait of Mario Klingemann

The approach of deconstructing and reconstructing forms to understand underlying structures and patterns has historical precedents in art. Classical painters such as Leonardo da Vinci conducted anatomical dissections to gain a deeper understanding of the human form. Similarly, Cubist artists such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque fragmented objects into geometric components, breaking them down and reassembling the forms to depict multiple perspectives.

Mistaken Identity, 2018 at ZKM in Karlsruhe during the Beyond Festival in October 2018

To understand how AI functions and perceives human forms, Klingemann developed a method called "neural glitch”. This technique involves deliberately introducing errors into fully trained GAN models. Initially, GANs are trained to generate realistic human faces. Once the models achieve a near-perfect state, Klingemann disrupts key neural components.

Mario Klingemann, Mistaken Identity – Chapter #1, 2018

These disruptions include small changes, such as altering, deleting, or exchanging the training weights, which impact the numerical values that determine how the model synthesizes images. These changes result in significant and often unpredictable alterations to the output.

Mistaken Identity, 2018 at ZKM in Karlsruhe during the Beyond Festival in October 2018

They affect both texture and semantic levels, changing the arrangement of facial features and altering finer details, such as skin tone or shading. These changes produce outputs ranging from slightly altered portraits to entirely abstract forms. This process represents how neural networks work, interpreting and perceiving human faces differently than humans.

Mistaken Identity, 2018 at Future U exhibition at RMIT Gallery, Swanston Street, Melbourne, Australia in 2021

The final result consists of three nearly two-hour-long videos, presented as a triptych for the first time at ZKM in Karlsruhe in 2018 and the Future U exhibition at RMIT Gallery, Swanston Street, Melbourne, Australia in 2021

The first chapter of the series, Mistaken Identity - Chapter #1, is part of the Seedphrase collection.

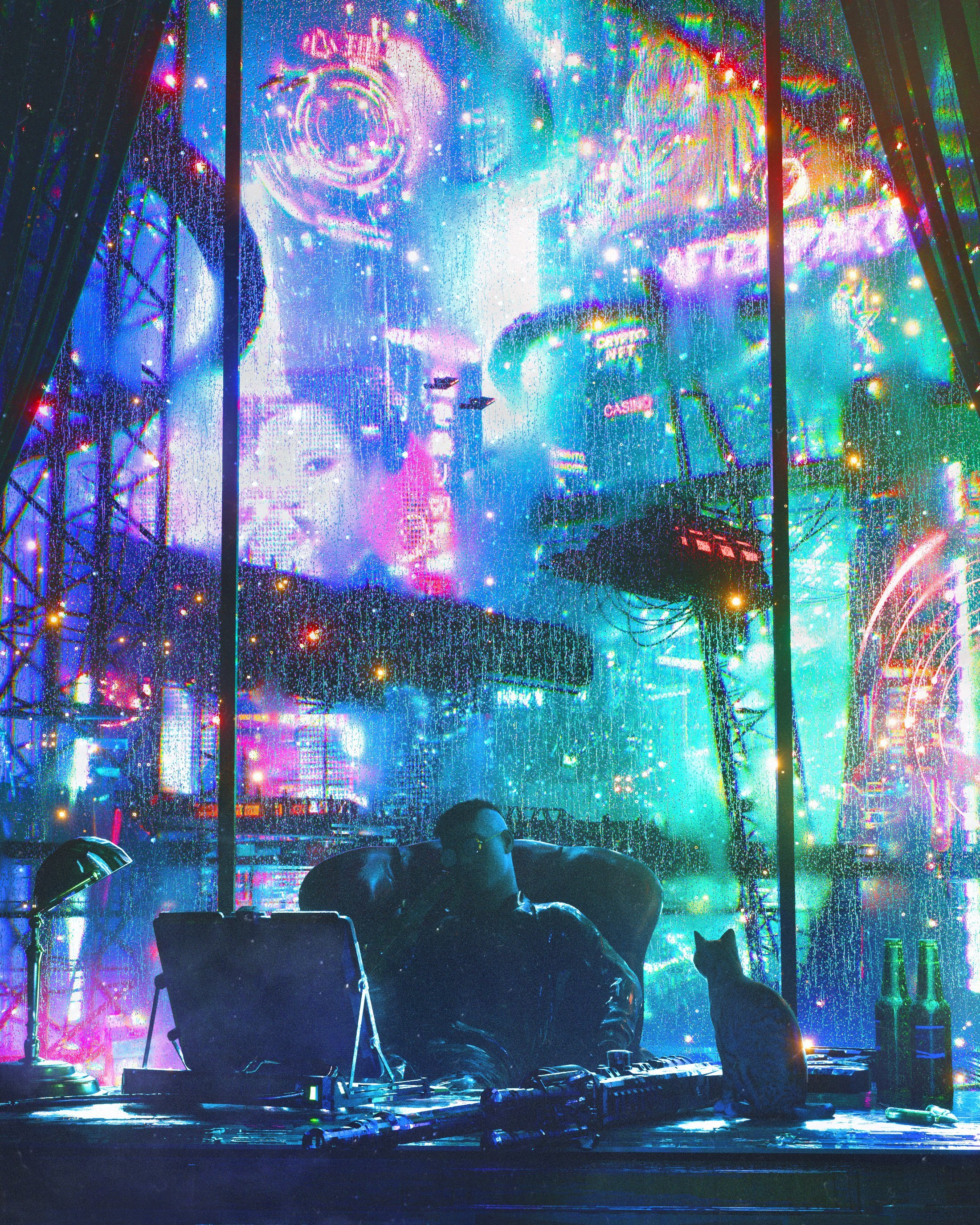

HISTORY OF GENERATIVE ART - Metaverse

Krista Kim, Mars House, 2020, Source: sothebys.com

The concept of virtual worlds and digital identities existed long before the term 'metaverse' became widely recognized. The origins can be traced back to early science fiction, which later inspired practical applications like gaming, virtual reality, and social digital spaces. Today, the rise of Web3 culture, including decentralized platforms, blockchain-based digital assets, and interactive virtual experiences, further integrates these virtual worlds into everyday life.

The metaverse refers to a network of virtual spaces where users interact through digital avatars. These environments support social interaction, digital economies, gaming, education, and more. It incorporates technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), blockchain, and traditional online platforms to create digital worlds.

Ivan Sutherland, Sword of Damocles, 1968, Source: researchgate.net

The foundations of virtual reality were laid in the 19th and 20th centuries with early discussions about immersive artificial environments. In 1938, French playwright Antonin Artaud described the illusory nature of theater as 'virtual reality' in his collection of essays, “The Theater and Its Double”. Another early theoretical concept is found in the writings of Stanley G. Weinbaum, whose 1935 short story “Pygmalion’s Spectacles” envisioned a pair of goggles that could transport users into an interactive world.

Stanley G. Weinbaum, Pygmalion’s Spectacles, 1935, Source: sothebys.com

By the 1960s, technology began catching up with these ideas. In 1962, Morton Heilig developed the Sensorama, an early immersive multimedia machine simulating a motorcycle ride with 3D visuals, sound, vibrations, and scents.. Later, in the 1960s, Ivan Sutherland created the first VR headset, the "Sword of Damocles", which featured mechanical tracking and wireframe graphics.

Morton Heilig, Sensorama, 1962, Source: historyofinformation.com

Neal Stephenson, Snow Crash, 1992, Source: goodreads.com

In the 1980s, the idea of simulated realities appeared more frequently in literature. In 1981, Vernor Vinge’s novella "True Names" introduced a virtual world accessible through a computer interface. In 1984, William Gibson’s "Neuromancer" described a digital space called "The Matrix", where users could navigate a connected network. These books, along with films like "Tron" (1982), and "Ready Player One" (2018) further explored these themes.

The term "metaverse" was first introduced in Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel, "Snow Crash”. In this book, the metaverse was a virtual space where people could escape from reality and interact in a 3D environment using avatars.

As virtual worlds evolved, artists and scientists explored their artistic potential. Active Worlds, launched in 1995, was an early online 3D platform where users could navigate virtual spaces, interact through avatars, and build their own environments. In 2005, @HerbertWFranke created the Z-Galaxy within Active Worlds. Unlike most virtual spaces, it featured mathematically generated structures, galleries, and a sculpture park. It first showcased Franke’s own work but later included exhibitions by other artists and scientists.

Herbert W. Franke, Z-Galaxy, 2005, Source: art-meets-science.io

Around the same time, video game developers experimented with multiplayer virtual spaces. In 1986, LucasArts released "Habitat", an early example of a graphical multiplayer virtual world that allowed users to interact using digital avatars. In 2003, the launch of "Second Life" brought the metaverse concept closer to reality. Users could create digital identities, purchase virtual land, and engage in social and economic activities.

Linden Lab, Second Life, 2003, Source: indiatimes.com

Steven Lisberger, Tron, 1982, Source: theguardian.com

The industry gained new momentum in the 2010s, with advances in computing power and graphics. In 2011, Palmer Luckey developed the Oculus Rift prototype, reigniting interest in VR. Companies like Oculus, Microsoft, Sony, and HTC introduced VR headsets that expanded the use of virtual reality beyond gaming, including business, education, and industry applications.

In 2021, Facebook rebranded as Meta to focus on metaverse development. Around the same time, Web3 technologies like decentralized finance (DeFi), NFTs, and blockchain governance were gaining traction. Companies and creators explored NFT-based digital ownership, driving interest in virtual land and new digital economies.

As technology advances, the metaverse has the potential to reshape how we connect, create, and experience digital life.

COLLECTOR’S CHOICE - Early AI video Works by Memo Akten

“We are all connected. To each other, biologically. To the earth, chemically. To the rest of the universe atomically.” – Neil deGrasse Tyson

Between 2018 and 2020, Memo Akten produced two early AI series: the "BigGAN Study" and "We Are All Connected", both representing his early explorations with generative adversarial networks. Both series feature audio-reactive visual compositions that respond to original music composed by the artist himself without the use of AI. The work reflects the interconnectedness of all forms of life and matter, from microcosm to macrocosm.

We are all connected #04 - Underworld, 2018-2020 by Memo Akten

For more than a decade, Memo Akten has been working with various AI models in his art. His works often focus on intelligence in nature, intelligence in machines, perception, consciousness, neuroscience, ritual, and religion. This interdisciplinary approach allows him to connect technology, science, and spirituality in his moving images, sounds, large-scale responsive installations, performances and audio-reactive visual compositions.

Portrait of Memo Akten

The history of audio-reactive visuals originates in the early 20th century, when experimental filmmakers began exploring methods to visually represent sound. Oskar Fischinger and Mary Ellen Bute developed early abstract animations synchronized with classical and experimental music. In the 1960s and 1970s, John Whitney further pioneered this field through the use of analog and digital computers to generate real-time synchronized visuals, where visual patterns corresponded directly to sound input.

BigGAN Study #2 - It's more fun to compute, 2018 by Memo Akten

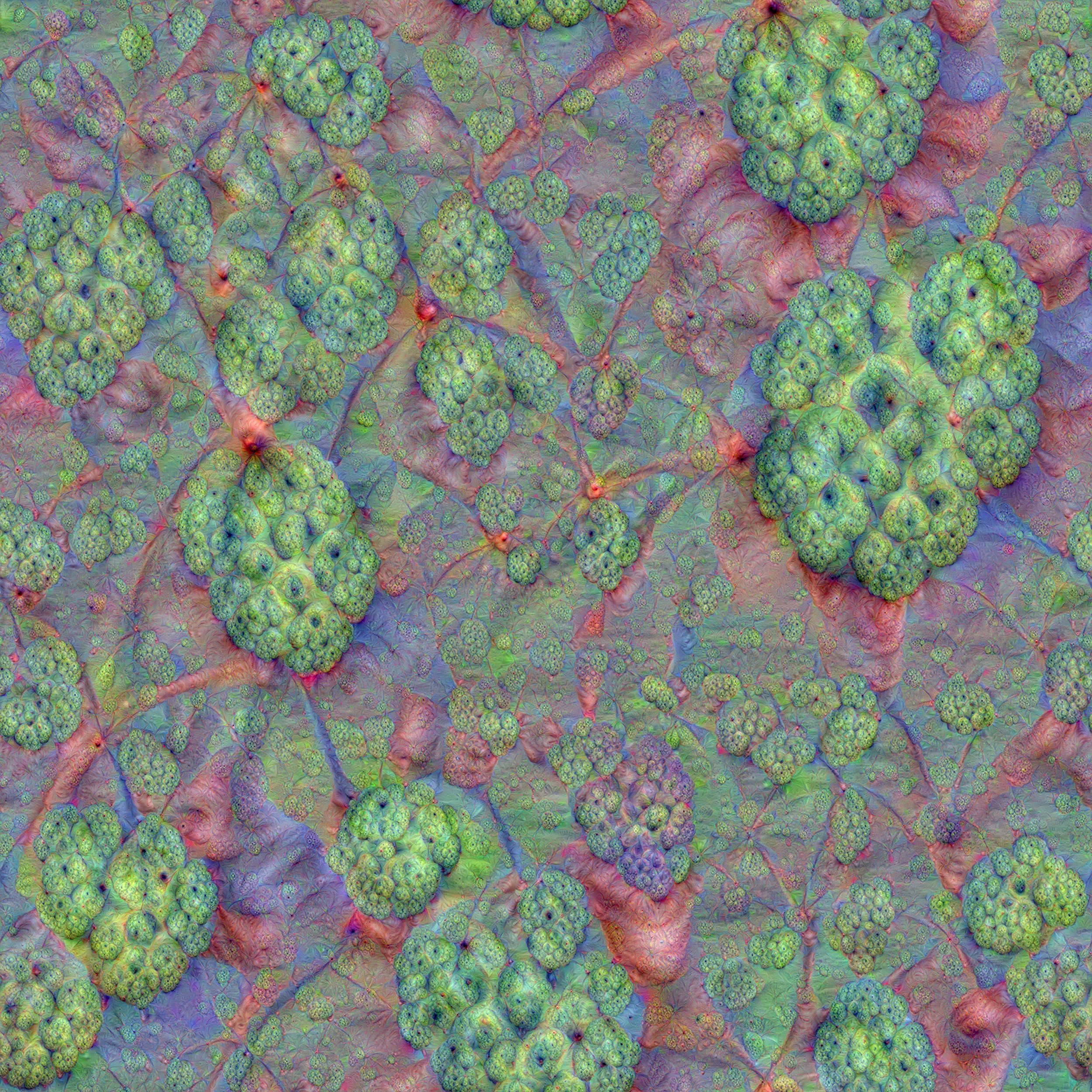

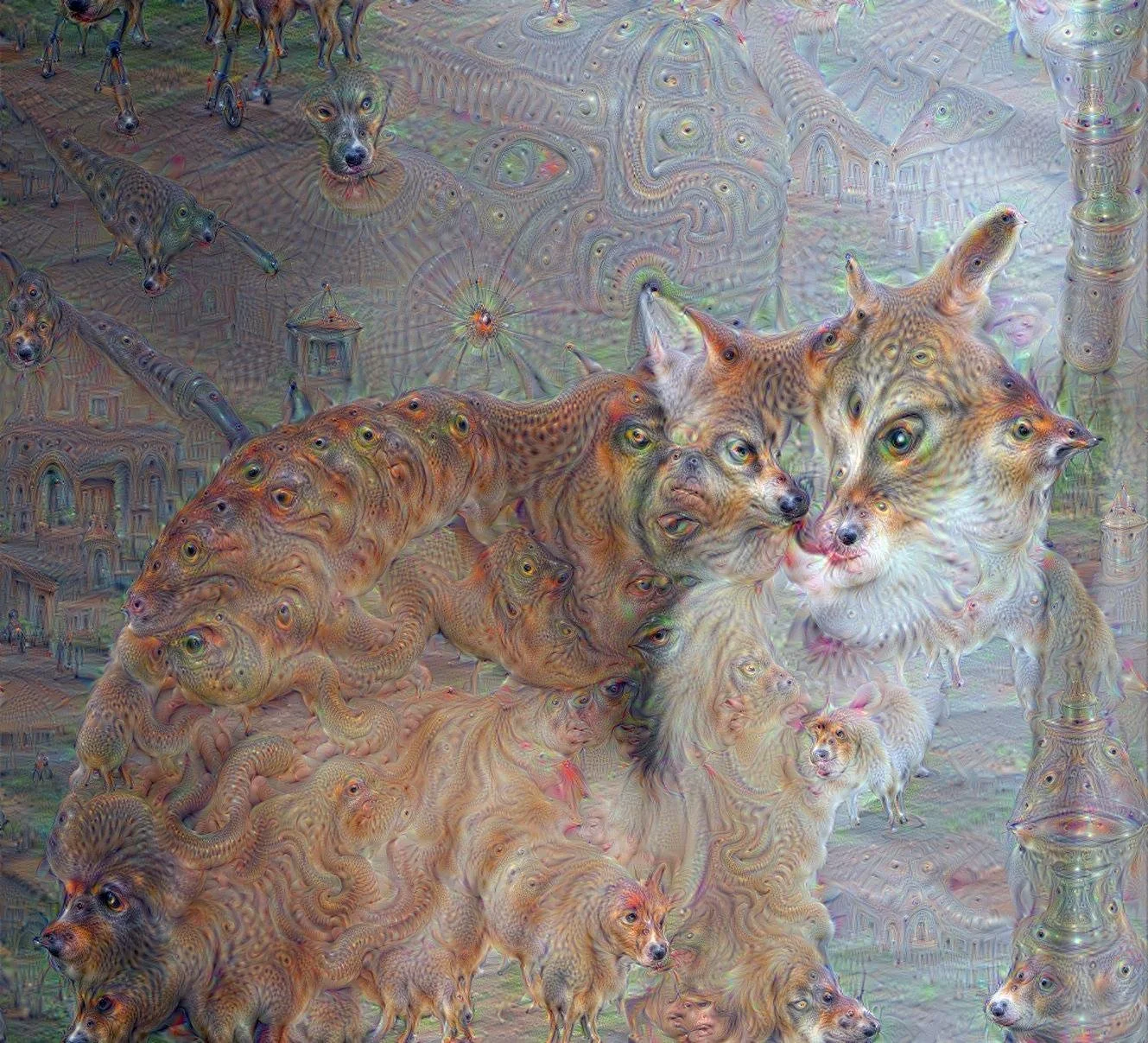

Memo Akten’s practice builds on this tradition. "BigGAN Study" is one of his first projects where he combined video with audio, producing audio-reactive visual compositions. Akten began working on this series in 2018, using an AI model known as BigGAN, developed by Google DeepMind. Compared to earlier GAN models, BigGAN had the capability to generate more detailed and diverse images due to its use of larger datasets and high-dimensional latent spaces.

BigGAN Study #4 - BigGAN Madness, 2018 by Memo Akten

BigGAN had the downside of relying on a large-scale dataset sourced from the internet. As Memo Akten became concerned about the legal and ethical implications of using inputs without consent, he began building and training his own AI models in 2017, sourcing images from the public domain, CC0 licenses, and his personal archive to ensure compliance with ethical standards. His second series, “We Are All Connected”, was created using this custom model between 2018 and 2020.

We are all connected #05 - Mad World, 2018-2020 by Memo Akten

The uniqueness of these series is that Memo Akten later revisited the videos, dubbing the visuals with original music he composed. For some of the videos, he created the music in the 1990s as a teenager using a 486 or Pentium computer, a 14-inch CRT monitor, FX pedals, an electric guitar, and Cakewalk software. The moving images in the works are synchronized to match the tempo and feel of these compositions.

We are all connected #06 - Plug me in, 2018-2020 by Memo Akten

Both series reflect Memo Akten’s philosophical concerns, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all forms of life and matter, from microbes to galaxies. The works are presented as continuously evolving images accompanied by Akten's own music. In both series, rather than relying on random latent walks, he employed deliberate, controlled explorations of the latent space.

We are all connected #08 - Avril 14, 2018-2020 by Memo Akten

The resulting works serve as meditative audiovisual experiences, that reflect the complex, interconnected nature of existence.

We are all connected #05 – Mad World is part of the Delronde collection.

COLLECTOR’S CHOICE: Letter Readers by Osinachi

Letter Readers (2024) by Osinachi is the artist's first-ever triptych, a choice that adds further significance to the piece, examining the transformation of communication and reading in the digital era.

The work reflects on both the advancements and the losses that have emerged from the shift from handwritten letters to instantaneous digital messaging. By selecting this format, Osinachi underscores the importance of the message and enhances its thematic weight, drawing on the triptych's historical and symbolic associations.

Historically, the triptych format was widely used in Christian art, particularly for altarpieces during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Triptychs often carry deep symbolic meaning, with the number three representing the Holy Trinity in Christian theology—symbolizing divine harmony and completeness. It is also seen as a representation of the passage of time—past, present, and future—or as a metaphor for the stages of existence: birth, life, and death. Through this format, Osinachi invites viewers to consider the enduring relevance of communication in all its forms.

Robert Campin, The Merode Altarpiece, c. 1427–32, Source: metmuseum.org

By reinterpreting the traditional three-paneled layout, Osinachi’s work reflects on the fading tradition of reading in the digital age. The triptych connects the past, when reading was a focused, tangible act, with our present and future, when these practices are slowly disappearing. Each panel shows an individual figure seated on a bench, absorbed in reading a long letter, evoking a quiet moment of attention that contrasts with today’s fast-paced, image-driven communication. Like many medieval triptychs, the work incorporates symbolism: the scroll-like letters, the repeated gestures, and the shared background all serve as visual metaphors.

Antonello da Messina, Saint Jerome in His Study, 1474–1474, Source: nationalgallery.org.uk

The long letters held by each figure resemble historical scrolls or parchment, suggesting a form of communication that requires focused attention. This stands in contrast to contemporary modes of information consumption, which prioritize speed and visual content over extended text. The format of the letter may also allude to the long threads we encounter while scrolling on social media. Despite the formal similarity, the experience is different: engaging with physical letters or books encourages sustained focus, while digital scrolling often results in fragmented attention.

Osinachi, Letter Readers 1, 2024

Although the figures are physically separated across the panels, the shared background and unified activity establish a visual and thematic connection. This shared focus highlights the complex relationship between connection and loneliness in modern life, where individuals are often alone yet continuously connected through the digital world. The natural surroundings, with its trimmed hedges and a clear blue sky, reflects how we are not only moving away from the tangible world, from analog communication and from reading but also from direct engagement with nature.

Osinachi, Letter Readers 2, 2024

Elements of Nigerian cultural heritage are also present in the work. While Osinachi’s figures represent contemporary individuals, dressed in hoodies, backpacks, sunglasses, and sneakers, the use of bold, patterned trousers draws on African textile traditions. This stylistic choice adds another layer to the narrative between past and present, connecting tradition with contemporary identity.

Osinachi, Letter Readers 3, 2024

The work makes use of the traditional triptych format in a contemporary context while also encouraging a slower, more intentional form of engagement. As the figures are shown absorbed in reading, the viewer is similarly invited to pause, take in the details, and reflect on the composition and its underlying themes.

Osinachi’s works can be found in the collections of museums such as Buffalo AKG Art Museum and Museum of Art + Light, as well as in private collections including Colborn Bell, SuperRareJohn, TokenAngels, and many others.

Osinachi, Letter Readers, 2024

The Interview I Art Collector @NGMIoutalive

"If you don't enjoy making your own decisions, you're never going to be much of a collector." – Charles Saatchi

Kate Vass continues her exploration of the perspectives of a new generation of art collectors. During our interview with @NGMIoutalive, the above quote came to mind, as it resonated with our conversation. Our guest reflects on how digital art connects to his values, lifestyle, and taste, emphasizing that for him, collecting is primarily about "having fun."

The conversation explores further the importance of community, with Bright Moments playing a significant role in merging digital and physical experiences, as well as the evolution of trends in digital art and the most cherished artworks from the collection.

It’s truly impressive that, through this playful approach, our guest has built a remarkable collection, including early GAN works, pieces from iconic artists, and captivating works by XCOPY. Perhaps "having fun" and "enjoying making your own decisions" are the secrets to staying perpetually connected to and excited about your collection.

We hope this interview provides further insight into @NGMIoutalive's journey. We hope you enjoy reading it as much as we enjoyed conducting the conversation.

Artonymous, ON FIRE, 2020

KV: Can you tell us a bit about your background? How did you first get into collecting digital art? Were you already involved in art collecting before discovering digital art?

N: I have been involved with blockchains on the infrastructure side and try to balance that by building things with my hands that might actually be useful to someone. For the most part I have lived a nomadic lifestyle going back to my early childhood. My parents had a small art collection which they took along wherever we moved. So, although I grew up around art, it was not until my early thirties that I became interested in collecting myself. Discovering NFTs played well into my lifestyle preferences, as I really enjoy being able to own something without having to amass physical items. That being said, my desire for more physical art and the concordant wish for having more wall space to enjoy it have unfortunately also increased since I have grown older.

Robbie Barrat and Ronan Barrot, Infinite Skulls, 2019

KV: Your collection includes crypto art, generative art, and AI art. Do you find yourself drawn to one of these more than the others?

N: I don’t have any preferences there. However, I do recognize that they each have their own narratives to which I relate in a particular way. I love generative art because I can appreciate how difficult it is for a computational system to creatively explore the randomness and grit inherent in the natural world. I love crypto art for introducing an emotive and human connection aspect to sovereign digital ownership, that was hitherto unimaginable in the digital asset context and I love AI art for challenging our ideas around aesthetics and what is considered to be “real”.

William Mapan, Naufrage II, 2022

KV: What do you look for when deciding to acquire a new piece?

N: I think the main underlying thing I am looking for when buying art is a connection. An aesthetic connection, a connection to the story of a particular work, or of a particular artist, and now with digital collecting also the connection to a particular community. I don’t have a specific strategy or end game in my mind when I buy art. It is an evolving process where I often end up surprising myself. I kind of hope it will always stay that way.

Max Osiris, Point of Contact, 2020

KV: You mentioned that, at first, you didn’t quite understand the appeal of GAN art but eventually grew to appreciate it. What was the turning point for you?

N: I guess the real turning point came with me spending more time reading about the ideas and processes behind how these works were created. Looking purely at the aesthetics, I often found them tough to swallow. They didn’t readily fit into my pre-conceived ideas of what art is or should be. They rubbed me up the wrong way if you will, and I wanted to understand why that was the case. When I realized the major technical breakthrough behind them, I became fascinated. People had created a synthetic neural network that was able to represent categories through an abstraction, rather than images themselves and utilized this as an artistic tool. It was a very brief moment in time that is somehow appreciated by a few for its significance.

DeepBlack #5388, 2019

KV: You now own quite a few AI-generated works, including early pieces by David Young, which often feature elements from nature. What is it about GANs’ interpretation of nature that resonates with you? Do you think AI can enhance our perception of the natural world?

N: The reason I like GAN art is because it often highlights a lack or “misinterprets” something that our visual conditioning would ordinarily take for granted to be represented in a particular way. Nothing is so close and familiar to us as the random complexity of the natural world. Experiencing a disruption of that can make us take a step back and re-evaluate our point of view. We are generally very quick to think that we have understood something or know something, but if we get a chance to take a different perspective, we can discover worlds hidden within worlds. So, what I think we can say is that the alchemical process of dissolving and coagulating that happens in machine learning is ultimately a diminished reflection of our own neural processes and can give us some interesting clues about how we operate.

David Young, Learning Nature (b63h,4000-19,4,9,8,16,17), 2019

KV: You also own several pieces by XCOPY. What is it about his work that stands out to you?

N: I think XCOPY understood very early on how powerful memes can be. His decision to store and proliferate his work, in what back then was still a very much anarchic and disintermediated context of the blockchain, was nothing short of revolutionary. His brilliance lies in capturing some of the ideas that users of a highly interconnected, online-society mutually believe in, while simultaneously putting them up on the stake. The hypnotic loops hold a mirror to our face and say: “Take a look”, without necessarily passing judgment and it is hard to look away when we find ourselves reflected so clearly in our wanton state. Besides all that, I just find the aesthetics of much of his work incredibly captivating and unique.

XCOPY, Deathless, 2020

KV: You’ve been part of TheDoomed DAO. How has participating in these communities, as well as engaging with other collectors or figures in the space, shaped your perspective on digital art and collecting?

N: I think one of the key differentiators with digital art is the networked aspect. Although I have collected physical work by well known artists, I do not know anyone else who has, let alone have any insight into what other art they have collected, what interests them, for what particular reasons, etc. Even being loosely part of a community, like this one, creates the sense of sharing a passion or interest that appears hard to replicate in a trad art context.

XCOPY, Grifter #400, 2021

KV: How important is the physical aspect of blockchain-based art to you? Do you see a growing role for hybrid experiences in digital art collecting? Have you collected physical works alongside digital ones?

N: If I am perfectly honest a lot of my favorite pieces that I collected during the last years sit somewhere at the crossroads of digital and physical art. That has perhaps also something to do with the fact that I truly enjoy creating physical objects myself. In terms of blockchain-based hybrid experiences, Bright Moments has done some pioneering work, which I was lucky enough to attend on several occasions, at some truly spectacular locations around the world. I think there is still a lot more potential to create a unique sense of value for people, by combining the excitement of digital ownership with physical pieces and extraordinary IRL experiences.

OxDEAFBEEF, Hashmarks #90, 2023

KV: You're quite active on X, sharing your thoughts on art and the pieces in your collection. Do you think collectors play a broader role in shaping the digital art space?

N: I do find it very special to engage with other collectors on socials and feel that the public forum represents a great opportunity for sharing the stories of art, artists and collectors in a defining way. On the flip side, that can also accentuate the same social power laws under which we are used to operate IRL, where influential figures are able to dictate tastes and preferences. While there is nothing unusual in that per se, the nature and speed with which socials operate can make people vulnerable to manipulation and impulsiveness and I am not one to be immune to that myself.

Harvey Rayner, Fontana #128, 2022

KV: Which artworks in your collection do you consider the most iconic, and why?

N: If I had to pick three it would probably have to be:

1. NO FAVOUR (COLD) by XCOPY

2. Meridian #87 by Matt des Lauriers

3. Head in the Metaverse by Popwonder

The first, because it is such a quintessential example of XCOPY’s work that has its origin in the Tumblr days and has 1/1 incarnation on Superrare. The second, because Meridians to me are just one of the most beautiful examples of blockchain-based generative art and this particular one has been featured at several Exhibitions in London and Taipei, and finally the Popwonder piece because it captures the vibes of JPEG summer like a few other pieces out there.

Matt des Lauriers, Meridian #87, 2021

KV: If you had to describe your collection in three words, what would they be?

N: Me having fun.

***

*The responses provided in this interview have been preserved in their original form, with no alterations to the interviewee's stylistic choices or grammar. - Kate Vass

@NGMIoutalive on X: @NGMIoutalive

@NGMIoutalive’s collection link: https://opensea.io/0x5078d1e25a84a3aa133c9c5de5c46c84384ddd93

The Interview I Art Collector Coldie

In the latest edition of our ongoing interview series with art collectors, Kate Vass had the opportunity to speak with Coldie, an artist and a collector who has become an influential figure in the space. As both a creator and a collector, Coldie offers a unique perspective on the intersection of art, technology, and the crypto space. Over the years, he has amassed a collection that not only represents the early days of blockchain-based art but also reflects his personal evolution as a collector. Coldie has been involved with the scene since 2018, and his approach to collecting is driven by more than just financial gain—it’s about supporting fellow artists, nurturing the growth of digital art, and contributing to the broader cultural conversation within the crypto community.

In this conversation, Coldie shares insights into his philosophy on collecting, the artists and works that have shaped his journey, and the transformative role of blockchain technology in the art world.

We hope you enjoy the conversation and find inspiration in Coldie’s approach to both collecting and creating art.

KV: In the early days of blockchain art, did you feel like you were part of something revolutionary, a new model challenging the traditional art world? How did that sense of pioneering shape your approach to collecting?

C: I knew that what I was getting into was going to be important for digital artists. As an artist, I was minting my artworks that I had been showing at regional art galleries, but now I was able to share them globally 24/7.

Soon after minting my own art and seeing what the market was offering for works, I knew that my art was worth more than what I was selling it for, but that wasn’t up to me to decide what ‘market rate’ was at the time. With this thought, I realized that early collectors with a savvy eye were going to be the big winners. I began taking 30% of my art sales and reinvesting in digital art. I was only spending about $30 per piece, but looking at what I have collected in that period 2018-2020, I am quite proud of.

Larva Labs, CryptoPunk #7933, 2017

KV: Do you relate to the expression by Andy Warhol - "Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art." Warhol saw business as a kind of art. Do you see this in crypto art, where art, value, and market overlap? How much does the business side shape your collecting?

C: I believe there are different reasons that each collector aligns with art. Some are gravitated to the image alone. Others are looking for a deep story. Others want to be part of a larger ecosystem or community. Others want to play games.

When I examine art that I am considering collecting, my first gut check is the “ok, so what?” test. Does this artwork strike me in a special way? Is there a message that I pull from it? Is it just a neat ‘3D bouncing ball’ or is there context and thought that adds to the artwork? Is this a business with the intent on maximum revenue generation, but lacking in artistic merit? What do I think this artist will be doing in 20 years? My time horizon for art collecting is multiple years, some pieces forever. Trying to figure out if I can 2x in a month is not the way I operate with collecting. If I wanted that, I would just shitcoin.

Osinachi, A Taxi Driver on a Sunday, 2020

KV: Can you tell us about your very first acquisition? How did you decide it was worth collecting? Was a support to your fellow artist or someone you came across for the first time and felt compelled to collect the work?

C: Pinpointing my VERY first token collected is easier said than done. I have looked back at my earliest SuperRare collected pieces and one that is in the ballpark “The unknowns 6.9” by artonymousartifakt. Collected on November 9, 2018.

It took me a few months to collect my first piece, but I remember instantly being interested in AI art, especially because it was so abstract but able to hold deep meaning. This piece in particular struck me because I felt like the top left person was Mark Twain, but at the same time, it could be anyone. Each character “could be” a certain person from history, but that is also the point of it, to me, was that these general portraits are in fact any number of people throughout history. That self-created narrative is what drove my purchase.

Artonymousartifakt, The unknowns 6.9, 2018

KV: How has your collecting philosophy evolved since you began? Have certain experiences or trends influenced the way you approach collecting now?

C: When collecting an artwork, especially a 1/1, it needs to have the ‘it’ factor. That factor can be from any and all styles of art. I have surprised myself when I am struck by an artwork I never would have expected to collect.

With so many options of art to collect, it is impossible to buy it all as I am an artist and not running a hedge fund. The discerning eye is my secret weapon that has pulled my interest in areas that were not where ‘the herd’ was collecting at the time. I was very interested in AI art. Got a bunch of really great pieces. I was into metaverse wearables. Got some legendary pieces. Early ArtBlocks was magical and I snagged some amazing pieces.

My tastes are always evolving. AI art is everywhere, so for an AI piece to have ‘it’ there needs to be narrative and meaning that pushes it above the rest.

MaxOsiris, Right Click Save as "Right-Click-Save-As-Space-Lasagna-Guy.gif”, 2023

KV: Your “Decentral Eyes” series features key figures from the crypto world. What draws you to these individuals, and how do you decide who to represent in the series? Are there specific qualities or contributions you look for when choosing subjects?

C: Decentral Eyes was born out of the goal to contextualize the faces that were shaping the crypto space in real time. I wanted each portrait to be a timely reference to where and what was going on at the time. I have a stance that each person featured ‘raises their own hand’ by doing something noteworthy that is historically relevant to the progress of the space. Vitalik made perfect sense to be the first featured because his technology was powering the very token the art is minted on. Others like Warren Buffett whose statements against crypto were just as crucial at the time. I enjoy taking Warren Buffett’s negative stance and using their wide recognition to start a conversation with those not aware of what crypto is about. This series is meant to be educational and historical by nature so that in 10 years when we look back, we have a visual scrapbook of these influential people. There have also been A LOT of people I chose not to include in the series because I also feel that doing a portrait of someone personifies that energy into the universal consciousness and I do not want to give them that power.

Coldie, DEyes #083, 2021

KV: How important is the artist's story, process, or connection to the crypto space in your decision to collect a work?

C: It is very important. In a space full of grifting and artists who disappear except for when the market gets hot, having a deeper connneciton to the overal digital art space is important not only for those I support, but also for the investment of what I hope they do over the span of their artistic career.

XCOPY, No Favour (cold), 2019

KV: The early space has seen explosive growth—are there artists or artworks you feel are often overlooked or misunderstood? And why? if you can give an example of any now?

C: Explosive growth has a way of pushing a select few to the top, while most are buried in the noise. The jury is still out on a lot of art I have purchased between 2021-now. Many of the artists and projects are early in their journey. I will keep watching for these artists to grow and evolve. Art is a forever journey. Putting in the time and creating art and being experimental to grow is a key distinguishing factor to pieces I collect. I love seeing artists take risks outside of what they are expected to create. Through this process there is huge growth.

Helena Sarin, an eternal tangle of what ifs, 2018

KV: What were the early days of blockchain art collecting like? Any particularly unforgettable moments or surprise stories?

C: The early days were a lot more holistic. Collectors had an understanding back then to allow others to get pieces and not hoard them for themselves. It was smart because it created a larger varied collector base. One of the most heartwarming experiences was when Tokenangels and I were in a bidding war for a Robbie Barrat AI Generated Nude as part of a charity art auction by XCopy. TA obviously had a lot more money than me to bid. I had saved up 6 months worth of sales and went all in. After a manual bidding war held by XCopy, I placed a bid at the exact moment that XCopy and TA thought was final and TA would win. When he clicked the button intending for TA to win, my bid slid in, and was awarded the art. I had a call with TA and told him that I was a man and would forfeit the token to him. He told me that he was willing to have bid a lot more for the piece, but also he was OK with me winning the piece as he held another in his collection. I will never forget that kind gesture.

This is a screenshot that was taken of me while gazing at the Robbie that I would later win. These metaverse memories are just as real as real life.

Screenshot of Robbie Barrat, AI Generated Nude Portrait #7 Frame #153, 2018 in the metaverse

KV: Are there artworks you own that have become especially meaningful or valuable over time, both personally and in terms of market significance?

C: One of my favorite series that I minted was Matt Kane’s Gazers. I have always been a huge supporter of Matt’s creativity and minted based on what I know about him as a very thoughtful artist, not fully understanding the depth of the series until later. The RNG gods were on my side when I minted (Gazer #812) and turns out to be one of the Gazers that is often spoken about as one of the most sought-after.

Matt Kane, Gazers #812, 2021

KV: What do you think the future holds for blockchain-based art? Where do you see this movement in five or ten years for you as collector and artist?

C: In time the world will more and more be turned into a society that inherently values and holds assets that are digital. I believe this will start with a broad understanding of Bitcoin’s value proposition and will extend into rare digital assets including art. While not every art piece will be deemed ‘valuable’ there are artists who have been minting over the past 10+ years as well as art being minted moving forward that will capture the collecting communities psyche as being truely rare and value will be derived from that. There are thesis that today will grow in understanding as well as many that will prove to not stand the test of time. In the end, it is the collective demand for rare assets that will drive price discovery.

It is equally interesting to watch those who have deep conviction for artworks and artists and how this plays out over time. I believe all art has different horizons of realization and it’s fascinating to see how time affects the demand for artworks and when each collector decides to make artworks available for purchase.

Beeple, BULL RUN #105/271, 2020

KV: Do you believe that digital art can only stay digital, or how do you display works from your collection at home? (any artifacts, prints or else)

C: Digital art is digital by nature. I think there are ways to collect digital pieces in physical form if the artist created a physical version that is signed/numbered. I have some physical counterparts that I love, including my “Baby Maker” Ringer #997 print I purchased from Dmitri Cherniak.

Over the years I have come up on some amazing artifacts from my journey. Many of them are physical pieces that were gifts from artists and I love displaying them around my studio and at home. They mean so much to me as they are relics of a time and place that I was directly connected to.

I also have several digital screens that I have the cycle artworks at home. Its wonderful when a cool piece pops us and my family asks more about it. That is what its about. So much more rewarding than doom scrolling my wallet. That is not how art is supposed to be experienced.

Dmitri Cherniak, Ringers #997, 2021

KV: How do you see the role of DAOs or community initiatives in the future of digital art collecting?

C: I believe community is the lifeblood of all cultural movements. There are any number of ways to harness this collective energy. I have seen some beautiful initiatives happen in my own community by collectors who have ideas and get excited to take my artworks and get them out into the larger world around us.

As a collector, I appreciate the ability to have a direct contact with artists. Often times its just cool to say “what’s up” in a group chat and to tell them how their art affects me. Paying it forward is a highly under utilized energy in society and I have seen first hand how a kind gesture or words of encouragement can really help someone. Sometimes it hits so hard for reasons unknown and it propels them to break through to their next big idea. That is what we can do for those around us, whether it is here in the crypto art community, or in our daily lives with people we interact with.

Espen Kluge, cruise ships and police cars, 2019

***

*The responses provided in this interview have been preserved in their original form, with no alterations to the interviewee's stylistic choices or grammar. - Kate Vass

Coldie on X: @Coldie

Coldie’s collection link: https://opensea.io/Coldie and https://opensea.io/ColdieVault

The Interview I Art Collector NIFTYNAUT

Interview with art collector Niftynaut

As we step into a new year, we continue the ongoing series of interviews with some of the most fascinating voices in the digital art space. Kate Vass is excited to kick off with the first of this year's interview with collector NiftyNaut.

NiftyNaut’s collection spans historical milestones like CryptoPunks and Autoglyphs, as well as emerging projects and experimental works that challenge traditional definitions of art. What sets NiftyNaut apart is a thoughtful approach to collecting—one that prioritizes storytelling, innovation, and a deep connection to the artist's journey over hype or market trends.

As Charles Saatchi once said, "The role of the artist is to ask questions, not answer them, and the role of the collector is to ensure those questions continue to be asked." Visionaries like NiftyNaut play a crucial role in supporting emerging movements and amplifying the voices of digital creators, ensuring the space continues to evolve and inspire.

In our conversation, we dive into what makes a piece culturally significant, the evolving role of NFTs in art history, and his vision for redefining how digital art is experienced. Whether you're an art collector, creator, or curious observer, this dialogue offers a rare glimpse into the mind of someone shaping the future of art in the digital age.

Larva Labs, CryptoPunk #2460, 2017

KV: What was the first digital art piece you collected, and why did it resonate with you?

NN: It was CryptoPunks. When I stumbled across them I thought it was different - I am one of the 267 wallets that actually claimed them. I recognised it as something pioneering as you could suddenly proof ownership of digital items. That was a game changer for me and I went down the rabbit hole.

Larva Labs, Autoglyph #173, 2019

KV: Your collection includes notable works like CryptoPunks and Autoglyphs. What draws you to these iconic series, and what role do you think they play in art history?

NN: Two angles that really interest me: what constitutes art in our digital(-native) world and the technical nerdy nitty gritty parts to make digital art. I’m captivated by how Punks challenge our traditional notions of art. Those 24x24 pixels combine simplicity and cultural impact and became symbols of digital identity. They are basically reducing art to its essential digital elements. From a tech POV it is the pioneering, kicking-the-can kind of stuff I appreciate. Punks pushed the enveloped and introduced verifiable digital scarcity with a simple original implementation that ended up inspiring the entire NFT / tokenisation-of-everything movement. What makes Autoglyphs remarkable is that they were the first project to generate and store their art entirely on-chain. Simply put: LarvaLabs created with Punks and Glyphs something aesthetically and technically meaningful that met community adaptation and let to subsequent innovations.

Larva Labs, CryptoPunk #3288, 2017

KV: Are there any lesser-known artists or collections in the NFT space that you’re particularly passionate about?

NN: Two in particular: MCSK (@mcsikic) and Material Protocol Arts (@material_work). MCSK is such a versatile artist who is exploring the concept of time in his works. He is incredibly talented, loves tinkering and is using different media and tools. I started my own art residency with hon.art, with him as the first artist in 2024, and he just created those incredible sculptures to display digital art. Material Protocol is a studio that is pushing the boundaries with 'Cycles’. Their project uses the blockchain as its canvas, it is interactive and creates an evolving digital sculpture that records its own history and changes over time. Both MCSK and Material Protocol experiment with and explore the concepts I am interested in.

MCSK, Gameboy, 2024

KV: How do you stay ahead of trends in the rapidly evolving NFT and digital art space?

NN: I don't. It was manageable when the space was smaller and 'NFT' was synonymous with digital art. But now NFTs have become an umbrella term, with platforms popping up everywhere tokenizing everything - it's impossible to stay ahead, and I don't try to. Instead, I move at my own pace, exploring things I like and what friends share with me. Stepping back from the constant rush helps me focus on the bigger picture and avoid the fallacy that you always need to be first. Besides, most trends end up being overhyped and overpriced anyway.

Pxlq1, Dynamic Slices #488, 2022

KV: What’s your approach to evaluating the long-term cultural or financial value of a piece?

NN: I am really bad in evaluating the future value of a piece. I collect them because I like them. In my experience the things that aggregate value over time are the ones that don’t live on hype or utility as both will eventually fade. Take Punks as an example, it took some years before they moved to where they are. In my experience, innovative ideas are normally not necessarily understood in the beginning and it takes time to being adopted by a broader audience.

Ivona Tau, The cycle of night (lat. Nocte Cursus), 2021

KV: What personal philosophy guides your collection? Are you focused on investment, curation, or storytelling?

NN: While I was driven during the art blocks peaks from a gaming / competitive pov -I need to have a full curated set- I am nowadays somewhere between curation and storytelling. Curation in a sense of what pieces do I want to have in my wallet or what I want to share for an exhibition, what would spark a conversation with people that are not in this space and how could this piece convince them to explore digital art. And storytelling from a pov of the artist. I am quick in judging, and sometimes I judge pieces / artist absolutely utterly wrong because I don’t understand their journey or their message. So it takes sometimes a second or third look for me and some talks with family / friends / artists / others to truly understand what is behind a piece. And if I get hooked on a story I want that piece.

John Orion Young , Franny, 2021

KV: Do you see your collection as a legacy project? If so, what story would you like it to tell about this era?

NN: My collection turned into an attempt to tell the story of what fascinated me most about this era: the intersection of what constitutes art in our digital world and the technical innovation behind it. I'm drawn to works that challenged traditional notions of art - whether it's CryptoPunks showing how 24x24 pixels could become cultural symbols, or artists pushing the boundaries of generative on-chain art. Looking at my collection, I see pieces that forced me to rethink the very essence of digital art and its technical foundations. I hope future viewers will not just see individual pieces, but understand this fundamental shift in how we thought about art, ownership, and digital expression.

Kim Asendorf, Cargo #588, 2023

KV: How does hon.art redefine the traditional museum experience, and what aspects of Johannes Cladders' anti-museum philosophy were most influential in shaping this digital space?

NN: hon.art is the spectre of all unfinished ideas I had, that turned into this evolving digital collection and hub. I came across Cladders during some philosophical rabbit hole I went down regarding how to present and display digital art. His anti-museum philosophy just resonated with me: he rejected traditional museum conventions and he was viewing museums as living spaces for dialogue rather than static repositories. I'm still at the beginning with HON but I envision a translation of these principles into the digital age. I want to exploring algorithmic curation to create unexpected juxtapositions, build interactive archives that preserve both artworks and their context, and enable artist collaborations and a residence- something I did a first trial of in 2024. I envision simple systems for visitor-curated exhibitions and ways to show the evolution of digital artworks over time. The core principle remains true to Cladders: art shouldn't be locked in ivory towers - whether physical or digital - but should be an active part of social dialogue and everyday life. In an era of declining trust in traditional media, art remains one of our most powerful tools for confronting and exploring societal issues. Most importantly, institutions should serve art and people, not the other way around. This principle guides how we should approach both physical and digital art spaces today.

Jonathan Chomko, Natural Static #114, 2023

KV: The idea of a boundary-less, ever-evolving space is ambitious. How do you manage the tension between technological constraints and the goal of seamless accessibility for a global audience?

NN: Ha yes - something I am debating with myself ever since. I would argue that actually more people have access to technology than to a museum. I think the comparison though, shouldn’t be between universal access and limited access, but between different types of limited access, where digital actually provides broader reach. I mean digital distribution has loads of advantages like time flexibility (24/7, no queues), cost efficiency (mostly free, no travel costs, constant access and repeatedly), cultural accessibility (no language barrier), geographic reach. In my opinion, the answer lies not in trying to ensure universal individual access, but in creating new forms of collective engagement. Rethinking what we mean by "digital art" - perhaps it's not just about creating works that exist purely in digital space, but about using digital tools to create experiences that can exist meaningfully across different levels of technological access.

Harm van den Dorpel, Shasette, 2021

KV: What role do you see technology playing in making art an integral part of daily life, and how does hon.art act as a bridge between art and everyday experiences?

NN: Let me flip this question on its head for a moment. Rather than asking how technology can make art more integral to daily life, perhaps we should ask how art can make our increasingly technological daily life more human. Look, we're living in this fascinating paradox where technology has made art more accessible than ever - you can literally swipe through any museum during your morning coffee - yet somehow, our relationship with art has become more passive, more consumptive, more Instagram-friendly. Writing this, I think it shouldn’t be about bridging art and everyday experiences - it should be about disrupting the notion that art needs a bridge at all. Technology should be breaking down the white cube mentality, not just creating a digital version of it. Think about it: We're carrying supercomputers in our pockets that can render anything imaginable, yet we're still stuck in this mindset of art as something that happens 'over there,' in galleries or museums. The truth is, if we're doing this right, the line between art and everyday experience should become blurred.

Steve Pikelny, Dopamine Machines #270, 2023

KV: Looking back, is there a specific piece or moment in your collecting journey that stands out as particularly meaningful?

NN: While claiming Punks was the start, I think the most meaningful shift happened slowly over time. I went in with this completionist / rarity mindset and evolved into something deeper. I started spending more time understanding artists' journeys and messages, having conversations with friends and family about the pieces. That's when collecting became less about having and more about understanding.

Xcopy, ICXN #186, 2024

KV: What advice would you give to someone just starting their digital art collection?

NN: Buy what you like, not what others tell you.

MCSK, REframe _ III, 2024

KV: If you could add any one piece to your collection—regardless of cost or availability—what would it be and why?

NN: A piece I have seen at the cavernous exhibition halls of Amos Rex in Finland by Japanese composer and artist Ryoji Ikeda. It was an audiovisual installation on a 5x10m screen called data-verse and it was just stunning.

Ryoji Ikeda, data-verse 2, 2019

***

*The responses provided in this interview have been preserved in their original form, with no alterations to the interviewee's stylistic choices or grammar. - Kate Vass

Niftynaut on X: @niftynaut

Hon.art collection link: https://hon.art/

The Interview I Art Collector VonMises

Interview with art collector VonMises

As the year comes to a close, we are excited to share our final interview of the year with a true pioneer in the digital art space, VonMises. A long-time admirer, Kate Vass first encountered his insights during the early days of ArtBlocks.

We are thrilled to share this conversation with VonMises, a prominent collector known for his deep appreciation of digital art. VonMises stands as a testament to the pioneering spirit of collectors who saw the potential of blockchain technology long before it became mainstream. Through our dialogue, we dive into his journey, the inspirations behind his collection, and his insights on the future of digital art.

We hope you enjoy this interview as much as we did.

KV: Could you describe the moment or event that catalyzed your transition from traditional finance to the cryptocurrency world? What initially drew you to Bitcoin as an early adopter?

VM: It was in April of 2011, I was reading up on one of the financial market blogs and saw a story that caught my attention. It was an article on a new currency called Bitcoin. As a financial markets nerd, I was immediately interested. Within a week of reading that article, I had purchased my first bitcoins, from the now defunct Japanese based exchange MTGOX, and my world began to change in ways I could have never imagined.

I had felt for a long time that the world needed a digital cash equivalent, something that allowed a person online to transact without the need for an intermediary and in an anonymous way. While many others had tried, Bitcoin solved a lot of the problems that had caused other digital currencies to fail. While I wasn't sure at the time that BTC was a game changer, I knew having some exposure to it made sense.

Dmitri Cherniak, The Eternal Pump #3, 2021

KV: You acquired 60 CryptoPunks within the first month of discovering them. What convinced you that they were worth such a significant early investment?

VM: I've always been into collecting during my life from coins, to sports cards to watches and a few others, but when I came to NFTs and specifically CryptoPunks I knew I was looking at something special. In a lot of ways, it almost felt like my whole life had prepared me for this moment as CryptoPunks combined trading, collecting and crypto all into one! I remember telling my wife that I thought Punks were the best collectible I'd ever seen and that they would easily go up 10x in short order. Here's one of my first discord posts from April of 2020. In April of 2020 you could buy a punk for $150-200.

@VonMises14’s post on X from 30.04.2020

KV: You use CryptoPunk#1111 as your digital representation. Could you share what this piece personally means to you?

VM: While I have owned many rarer and more valuable punks, when I bought punk #1111 for 1.111 eth in September 2020, he just really resonated with me. For me repping a punk was never about making a digital flex, it was always about sharing in a community and showing respect to all the builders and true pioneers in the space who also rep a punk. I also felt like punk #1111 looked like me, as much as a punk can look like someone I suppose, although I don't ever wear a silver chain! Now that I have a following and I'm known in the NFT space, it's me and the face of VonMises. I can't imagine ever using something else and I hope to pass him and the VonMises "brand" on to my daughter someday.

Larva Labs, CryptoPunk #1111, 2017

KV: You chose the name Von Mises, inspired by Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises. Can you explain why his views or he himself is important to you?

VM: Most people who study economics are taught "Keynesian" economics, a school of thought based on the ideas of John Maynard Keynes. This approach is widely accepted and taught around the world, and it’s what I was taught when I studied economics. However, I always felt there were gaps in Keynes' explanations of the business cycle and the role of government in the economy. After learning more about Austrian economics, especially the ideas of Ludwig von Mises, many of these gaps started to make sense.

The Austrian School emphasizes the importance of free markets, the distortions caused by central banks, and the real causes of economic recessions. It challenges the Keynesian view that government intervention is the key to economic stability. In fact, Austrian economists believe that such interventions often worsen economic problems by distorting market signals and misallocating resources.

I believe Ludwig von Mises would have strongly supported cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin if he were alive today. Bitcoin is a form of money that is valued by the market, not determined by government decree, which aligns with Mises’ view on the importance of market-driven money and the dangers of central bank control.

DEAFBEEF, Series 0: Synth Poems - Token 124, 2021

KV: How do you balance personal interest with market trends when collecting NFTs? Do you always follow investment principles, or do you sometimes buy purely for enjoyment?

VM: I tend to be a completionist in my collection style, so if I decide I like something I will want to have all or as much of it as possible. While I try to stick to a relative value framework I do also buy NFTs for personal reasons and enjoyment value.

Dangiuz, Flyswatter, 2022

KV: Your collection spans CryptoPunks, XCOPY, Beeple, Bored Ape Yacht Club, Tyler Hobbs, and DEAFBEEF. How do you manage such a varied portfolio, and are there specific styles or genres you’re particularly drawn to?

VM: I'm really trying to assemble a collection of early, historically significant and culturally relevant art and collectibles from this golden era of digital assets. Many times I'm able to spot which ones will fit this before they run up in price like XCOPY, Punks and Art Blocks, but sometimes I don't see it in time and have to make a decision much later and at a much higher price. While I try not to chase assets I miss out on early, on occasion I'll pay up to have something I missed that fits my longer term criteria.

XCOPY, Last Selfie, 2019

KV: You've expressed a general intention to hold onto your collection and mentioned not wanting to sell many items. How do you decide which NFTs to sell?

VM: For me having one of something is pretty much the same as having none because once I decide to buy I typically won't sell out of it completely. Thankfully my strategy once I decide I like something is to buy more than one. This allows me to hold a position and still allow room for some sales if others enter the space and decide they want to own some as well.

DCA, Genesis #183, 2020 (VonMises’ first Art Blocks mint)

KV: What initially drew you to ArtBlocks, and how did you first connect with Snowfro?

VM: Back in early 2020, the CryptoPunks Discord was a truly special place. There were only about 30 of us actively chatting daily about NFTs, discussing how Punks would one day be recognized as real art, and how museums would eventually own them. The relationships formed during those early days are irreplaceable, as the purity of that moment is something you can't recreate today. When you have a core group of true believers, all obsessively diving into the technology and fully convinced of its future, you create a unique bond based on shared conviction—not on money.

This is where I met Snowfro. He was incredibly generous with his time and knowledge and one of the most honest people I encountered in the space. I was quite active in the Punks Discord, frequently sharing my bullish takes on Punks, and we had many discussions around our shared belief in the future of the space.

Around September or October of 2020, Snowfro began talking about his new generative art platform, Art Blocks, which he was about to launch. As someone I respected and admired, I knew I had to be involved when Art Blocks launched to show my support for Snowfro.

Tyler Hobbs, Fidenza #592, 2021

KV: As an early member and curator of the Art Blocks curation board, what criteria did you use to select and endorse generative art pieces?

VM: In the early days of Art Blocks it was more about how the art felt relative to what I had seen in the past. With Art Blocks still in its infancy there wasn't a lot to go on. Often my criteria would be something like, would I be willing to hang this piece on my wall?

Dmitri Cherniak, Ringers #206, 2021

KV: You managed to mint 350 Chromie Squiggles. What attracted you to this project, and how do you decide which pieces to keep and which to sell?

VM: My support for Snowfro was the primary driver. When it comes to selling or trading, I would typically sell my least desirable pieces first and hold on to the better ones. On occasion I would list better pieces for sale but only if I had multiple examples and only at high prices. I firmly believe in the old trading mantra "sell when you can, not when you have to"

Snowfro, Squiggle #463, 2021

KV: You sold one of your Autoglyphs, #392, for 375 ETH, marking a significant transaction. Why did you decide to sell it at that time, and did the sale enable you to acquire other important pieces or invest in new projects within the NFT space?

VM: This sale happened in October 2021, to me the market had begun to feel like it had peaked. It wasn't clear but given how much the value of Autoglyphs had moved up, and given that I still had 2 additional Autoglyphs, it just made sense to let that one go. I'm sure some of the proceeds made their way into other art pieces, but I don't remember if it went to something specific.

Larva Labs, Autoglyph #392, 2019

KV: When you used 60 BTC for a purchase on Silk Road, did you ever imagine Bitcoin would reach its current valuation? Have you made any trades in your life that you consider mistakes or missed opportunities?

VM: When I was buying BTC in the early days, I mentioned it to lots and lots of investment professionals. My sales pitch was something like "there's a 95% probability that you'll lose all or most of your money, but here's why you should still buy it". I then went on to explain how the potential was there for 1000x type returns. While seeing BTC at 100k is well beyond what anyone could have realistically envisioned back in 2011, I did know big moves up were very possible and to reach the level of a true global currency would require more than a 1 trillion dollar market cap. In my opinion there are absolutely scenarios where BTC climbs well above 1 million USD. When it comes to mistakes or missed opportunities there's not a whole lot I'd change other than buy more of what I bought!

Hideki Tsukamoto, Singularity #253, 2021

KV: In addition to CryptoPunks, Fidenza, and Autoglyphs, you own works by generative art pioneers like Herbert Franke. What draws you to early generative art, and how do you view its importance in the NFT space?

VM: I feel it's important to pay respect to the pioneers of generative art for sure. I had the pleasure of meeting Manfred Mohr in NYC after purchasing one of his early works. It was very cool to see his studio and he showed me a lot of his early works and shared his journey as a true pioneer. He has the first computer hard drive disk he used mounted on his wall. It's about one meter in diameter and he told me it had a memory of like 5 kilobits! Owning an early Herbert Franke is something on my list, perhaps you can help me out here!

Herbert W. Franke, Math Art (1980-1995) - Math Art 95 - No. 3, 2022

KV: Having lived through multiple bear markets in both traditional and crypto finance, what strategies have helped you navigate these challenging periods?

VM: I try to always remember that It's never as good at the top as it feels and it's never as bad at the bottom as it feels. Markets always over react in both directions so try not to be too focused on the short term. I never let short term sentiment skew my longer term view. During the recent NFT bear market it's natural for people to just straight line extrapolate out the downtrend and assume we are headed to zero. For this to be true, You would need to accept that NFTs have no future, which to me is just insane to say. The benefits that blockchain technology brings to art and collectibles is nothing short of revolutionary and with near 100% certainty NFTs have a very bright future.

I try to always have a well thought out thesis that I can refer back to in times of distress. If you know what you own and understand why you own it, the short term means a lot less and you can stay in a position without being shook out by bad short term volatility or uncertainty.

Bryan Brinkman, NimBuds #187, 2021

***

*The responses provided in this interview have been preserved in their original form, with no alterations to the interviewee's stylistic choices or grammar. - Kate Vass

VonMises on X: @VonMises14

Collection link: https://deca.art/VonMises?filters=1&details=1&sort=ACQUIRED_DESC

The Interview I Art Collector Cozomo de' Medici

"Collectors are as responsible for the direction of modern art as the artists themselves." - Peggy Guggenheim

In this spirit, we continue our series of interviews with notable art collectors shaping the digital renaissance. Today, Kate Vass had the pleasure of sitting down with Cozomo de’ Medici.

Known for his sharp insights and bold approach to building a world-class digital art collection, Cozomo has become one of the most influential voices in the NFT space. From championing emerging talent to acquiring works from established digital masters like XCOPY and Beeple, Cozomo reflects on what it takes to define the art movement of our time.

In this exclusive conversation, Cozomo shares his thoughts on the parallels between the Renaissance and today’s digital art revolution, the role of community trends in shaping collections, and his philosophy on building a meaningful and timeless art collection.

Without further ado, we present our interview with Cozomo de’ Medici.

Tyler Hobbs, Fidenza #938, 2021

KV: Can you tell us about your collecting journey? Did you collect physical artworks prior to collecting digital pieces? What inspired you to start collecting digital art?

CM: My collecting journey started by accident.

I had dabbled a little in contemporary art before, but not enough to consider myself a collector.

Then, in 2021, I started hearing from friends about CryptoPunks.

I was intrigued and soon after, I found myself shopping for one.

But as I dug in through the Discord servers and group chats, I discovered a blossoming digital art community, with artists and patrons from all corners of the world.

A digital renaissance was underway, and I wanted to be a part of it.

And that made my Punk purchase even more important.

The Punk was to be my digital identity, but as you know, there are many in crypto who rep their Punks… so mine had to be unique.

Long story short, this led to my acquisition of a Zombie CryptoPunk in July of 2021.

What I intended as my first and only major art purchase, turned out to be the birth of The Medici Collection.

KV: How did you come up with the name Cozomo de’ Medici?

CM: The CryptoPunk I acquired - #3831 - was already known in the community as “CoZom”, for it’s a zombie punk with a COVID mask.

So the name too was partly a coincidence.

I then felt it was only natural to amend the name a little, to form my digital identity -

One that pays homage to the revolutionary Medicis of the past, while at the same time looking ahead to the future.

Larva Labs, CryptoPunk #3831, 2017

KV: What similarities do you see between the Renaissance and today’s digital art revolution?

CM: There’s one big similarity -

Digital art has long been a thing, since the 1960s.

But just now, thanks to the blockchain, it’s coming into prominence and reaching its full, groundbreaking potential.

There were plenty of great pictures from before the renaissance.

But that time brought out the very best of the medium, and masters that went on to define the very word “art”.

I feel we will see a new generation of digital art masters emerge from this renaissance, much like how masters of the physical canvas emerged from the previous one.

Operator, Human Unreadable #259, 2023

KV: As a well-known figure in the NFT and digital art community, how much do you feel the collective sentiment or trends in the community influence your collection choices?

CM: It impacts every collector, including me.

But here’s what I’ve learned…

Building a collection with a clear mission helps me from being too swayed by what’s happening day-to-day or week-to-week.

I cannot tell you how many artists I’ve chosen not to collect, only to see them completely stop making art or not make any significant progress in their art practice.

The key is -

You won’t get any kudos for not spending money or choosing not to collect what’s popular.

But making the right choices is what will compound over the long run and unlock what great collectors are really after:

An impeccable collection of art.

I don’t like to demonize following trends or collective sentiments.

And I feel the strong voice the community has is a great thing.

A good example is Comedian by the maestro Maurizio Cattelan.

I heard a collector or two say it’s perhaps the most iconic work of 21st century art.

And seeing how the community was really activated by the work, memeing it and even debating its merits - it’s hard to debate against it.

Together with Ryan Zurrer, we were actually the underbidders on the work, when it was sold this week at auction.

Sometimes, what’s popular is popular for a very good reason.

Helena Sarin, #adversarialEtching, after Modigliani, 2020

KV: Have there been moments where you've chosen to go against the grain?

CM: If you are collecting digital, you are going against the grain.

I have plenty of wealthy friends, that simply don’t want to take the risk of collecting digital art.

They have their gallery connections and would rather dabble in what is tried and true.

Many get lost in the nuances and debate that collecting X digital artists is more “going against the grain” than collecting Y artists.

But that misses the point.

So if you’re here acquiring and championing digital art, I salute you.

When I think of great collections that I admire, like the Rubells of Miami, what they have done is collect from a wide range of artists that represent the art scene of their times.

They’re painting a picture with their collection.

And that means striving to acquire the very best works from the masters of today, while also seeking out the next wave of talented artists.

It’s not one or the other… to build a great collection, you must do both.

My collection is a reflection of this core belief I have….

I collect works from artists I feel are not appreciated enough, like Goldcat, Jesperish, Niftymonki and many others…

Just like how I collect works from artists I feel have made a strong case for their place in today's art movement, like Helena Sarin, Sarah Meyohas, Beeple, Sam Spratt and of course… XCOPY.

Sam Spratt, VII. Wormfood, 2022

KV: You have a significant collection of works by XCOPY. When did you start collecting his art, and what drew you to his work?

CM: I started hearing about XCOPY almost immediately after I started collecting.

After speaking to collectors I deeply respected and artists of high regard, they all echoed the same point:

XCOPY is the defining artist of the crypto art movement.

He emerged from the Tumblr golden age, after a decade plus of making GIF art.

Then he finds crypto, minting across Ascribe, various now-defunct platforms, and on Ethereum, where he was an early artist minting on SuperRare.

His genre-defining works, his experiments with blockchain as a medium, and his aesthetics have overwhelmingly influenced the genre of crypto art.

I could keep going, but I felt his place in the movement was beyond question.

So then I set off on a quest to acquire what I could of his SuperRare series.

To be very honest, I never imagined having an XCOPY collection like the one I today have.

But as it would turn out, I found myself at the right place at the right time.

And my goal evolved to building a museum quality XCOPY collection.

After diving deep into his entire body of work and relentless research into his Tumblr archives, I realized X would be known for his character works.

So my first major 1/1 acquisition was his SuperRare genesis character work “Some Asshole”.

Followed by his genre-defining piece “Right-click and Save As guy”.

More recently, I’ve been fortunate to acquire what’s considered one of XCOPY’s best pictures “All Time High in the City.”

One interesting thing about X is that many of his great works are editions, so those too are represented in my collection.

Everything from his iconic “Last Selfie” to the cult classic “Mortal”, to his lesser known but critically important works like “VOID”, “Dirtbag” and “DE$CEND”

The last few works I mentioned were minted on now-defunct chains and platforms.

But with Dirtbag and other lost works, tokens still exist, preserving the history.

Collecting X is an ongoing pursuit, one I’m excited to continue.

XCOPY, All Time High in the City, 2018

KV: In the “Medici Minutes”, you share your collecting journey and insights. Why do you think it’s important to share these experiences?

CM: One of my favorite quotes about collecting is by Nasser David Khalili: ‘a true collector must not only collect but conserve, research, publish and exhibit his collection’.

I started the Medici Minutes to create a space to share my thoughts in longer form.

I wanted it to feel unfiltered, and just be my musing about art, collecting and crypto.

I also felt email was the best way to talk to tens of thousands of readers, in a personalized way, each week.

Each person who subscribes to the Minutes has raised their hand and identified themselves as someone who is interested in hearing more about digital art.

And each week, I try to share with them my learnings, mistakes and musings.

Claire Silver, complicated, 2021

KV: NFTs have introduced a new way to assess value in art, combining rarity with digital culture. How do you personally navigate between the financial and cultural value of a piece when deciding what to collect?