Automat & Mensch 2.0 - 5 years milestone

“The romance of art and science has a long history, albeit a mixed one. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), the artist and polymath active in the Florence of the Renaissance, still serves as the prominent example for the enormous creative potential flowing from the interactions of art and science.”

- Andreas J. Hirsch, The Practice of Art and Science – Experiences and Lessons from the European Digital Art and Science Network

As we walk into Kate Vass Galerie on this nostalgic May 29th, 2024, we feel like we're stepping back in time. It's been five years since the "Automat und Mensch" group exhibition fascinated everyone with its wide retrospective highlighting the history of AI and generative art in its attempt to cover 70 years of history in one location. Now, as we look back on this important milestone, we're taking a journey through how AI and generative art have changed since 2019, with both old favorites as our guides.

The exhibition, titled "Automat und Mensch", was curated with precision and foresight, showcasing a captivating mix of artworks by pioneering artists such as Nicolas Schöffer, Herbert W. Franke (still alive at the age of 91), Frieder Nake, Vera Molnar (still alive at the age of 95), Roman Verostko, Manfred Mohr, Gottfried Jäger, Harold Cohen, Benjamin Heidersberger, Cornelia Sollfrank, and Gottfried Honegger.

The show featured several generative works from the early 1990s by John Maeda, Casey Reas, and Jared S. Tarbell. Works by Matt Hall and John Watkinson, Harm van den Dorpel, Primavera de Filippi and Manoloide were also on display to represent the contemporary scene.

While the show’s focus was on the historical works, taking the name from the eponymous book by K. Steinbuch “Automat und Mensch” that inspired many generative art pioneers from the 60s, the shows also highlighted the wide range of important works by living AI artists like Robbie Barrat, Mario Klingemann, Alex Mordvintsev, Tom White, Helena Sarin, David Young, Kevin Abosch, Sofia Crespo, Memo Akten and Anna Ridler, whose groundbreaking practice has influenced many emerging artists since 2019.

As we journey five years back in time to revisit the show, our aim is to reflect upon the trajectory of AI in art and the evolution of generative art over the past half-decade. We explore the transformative impact of technological advancements, paying homage to pioneering artists who laid the groundwork, while also highlighting new artworks.

The Evolution of AI and Generative Art in a Historical Context.

From the intricate patterns of Manoloide's "Mantel Blue" to the surreal visions of Alex Mordvintsev's "DeepDream" experiments, the generative art scene has been defined by visionary artists expanding the limits of computational creativity for decades. While the fluid, organic imagery marks a shift from geometric abstraction, AI art is a subset of generative art, despite some disagreement that we have heard in recent months. Therefore, knowing the history of evolution is so important.

The commonly told story of AI art history often begins with Harold Cohen's pioneering work and then moves through the development of GANs and DeepDream, but this narrative overlooks several important early chapters. The “Automat und Mensch” exhibition aimed to highlight some parts of generative art history, showcasing the work of mid-20th century artists like Frieder Nake, Vera Molnár, Herbert W. Franke, Georg Nees, Gottfried Jäger, and others, who experimented with algorithmic art long before AI techniques became prominent.

Nicolas Schöffer, a pioneering figure, significantly impacted these developments with his works in cybernetic and kinetic art during the 1950s. Drawing inspiration from Norbert Wiener's cybernetic theories of control and feedback, Schöffer conceptualized an artistic process rich with feedback loops, circular causality, and a fundamental emphasis on movement. He created moving, illuminating sculptures and installations that emitted sounds in collaboration with engineers, architects, composers, and dancers. In his “Chronos” series, he designed these sculptures to be characterized by their responsiveness to external stimuli such as light, traffic noise, and ambient sounds, which actively influenced the movement and behavior of the works. Schöffer’s unique approach melded art, technology, and science. His work embodied the foundational principles of generative art by engaging dynamic systems to produce art, and his mechanical systems in artworks forecasted the later use of autonomous systems in art creation.

The 1960s were characterized by a fascination with technology and instant communication, prompting artists to experiment with electronic feedback using new video gear. Pioneers like Steina and Woody Vasulka played with different sounds and visuals. They were joined by others, like Edward Ihnatowicz, Wen Ying-Tsai, Gordon Pask, Robert Breer, and Jean Tinguely, who mixed biology with technology in their art. At the same time, cyborg art became popular, exploring the relationship between humans and machines. Writers like Jonathan Benthall, Gene Youngblood, and William Gibson introduced the term "Cyberpunk”. British artist Roy Ascott and American critic Jack Burnham also developed significant theories on the integration of art and life.

“In conceptual art, the idea is not only starting point and motivation for the material work, it is often considered the work itself. In algorithmic art, thinking the process of generating the image as one instance of an entire class of images becomes the decisive kernel of the creative work.” - Frieder Nake

With the rapid advancement of computer technology and the influence of Max Bense's information theory artists began leveraging autonomous systems such as computer programs and algorithms for artistic expression. During this period, artists often collaborated with scientists due to the limited availability of computers, which were primarily located in universities, research institutions, or large corporations. Pioneers of this movement, including Frieder Nake, Georg Nees, Vera Molnár, and Manfred Mohr, utilized computational processes to explore new aesthetic territories, each demonstrating the potential for machines to contribute to the creative process. Parallel to the rise of generative art, generative photography emerged, drawing from the experimental photography of the 1920s and concrete photography of the 1950s. This technique involves the systematic creation of visual aesthetics through predefined programs that perform photochemical, photo-optical, or photo-technical operations, merging traditional photographic methods with mathematical algorithms. The first exhibition to showcase these works took place at Kunsthalle Bielefeld in 1968, featuring artists like Hein Gravenhorst and Gottfried Jäger.

While these artists laid the foundation for computer-generated art, Harold Cohen was the first artist to introduce AI into art with AARON, a software considered one of the first AI art systems, which he began developing in the early 1970s. AARON used a series of rules defined by Cohen to autonomously generate images. This allowed the program to independently make decisions about composition. Cohen's software evolved from producing abstract monochrome line drawings, which he initially colored by hand, to creating more complex, colorful, and even representational forms with drawing and painting devices that he engineered.

The development of AI experienced notable fluctuations in progress, leading to periods known as AI winters. The first significant AI winter occurred in the 1970s, prompted by disillusionment due to overhyped expectations and resulting in substantial cuts in funding and critique of the technology. A similar downturn happened again in the late 1980s, marking another AI winter. This second period of stagnation was primarily due to the limitations of the AI technologies of the time and the constraints imposed by the available hardware. Despite these setbacks, interest in AI did not completely vanish. Instead, it veered in new directions as academic researchers and artists found alternative applications and methodologies for the technology.

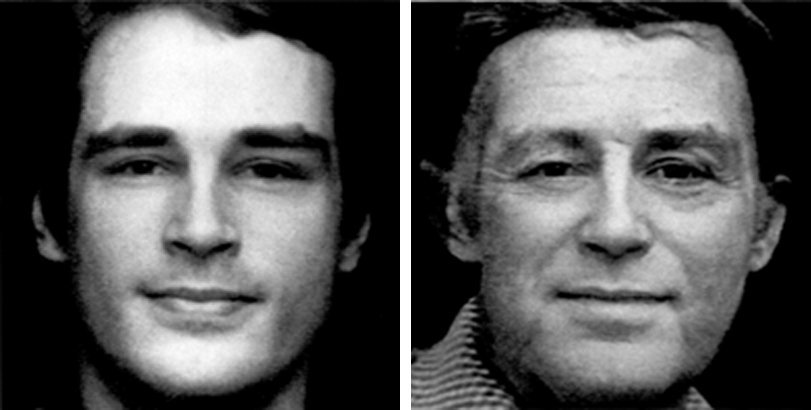

Nancy Burson, a pioneering artist from the early 1980s, is often overlooked despite her significant contributions to the intersection of art and technology. She is best known for her innovative work in computer morphing technology and is considered the first artist to apply digital technology to the genre of photographic portraiture. Burson’s creations are widely recognizable, even by those unfamiliar with her name. Some of her most notable works include the digitally morphed “Trump/Putin” cover for Time magazine. Burson developed her morphing software in 1981, known as “The Method and Apparatus for Producing an Image of a Person’s Face at a Different Age”, while she was at MIT. This technology was used in her interactive installation, the “Age machine”, which simulates the aging process and offers viewers a glimpse of their future appearance. Through her cutting-edge work, Nancy Burson explores questions about identity and aging, highlighting social, political, and cultural issues, and focusing on societal biases and injustices. Her works will be exhibited at LACMA this year, continuing to underscore her role in shaping how technology is used in artistic practices.

We must also highlight Roman Verostko, another pioneering generative artist from the 1980s. In 1982, he developed "The Hand of Chance", an interactive generative art program that executed his art ideas on a large PC monitor. Later, Verostko's interest shifted toward printed versions of his works. By the late 1980s, he had developed a program that controlled the drawing arm of a pen plotter, enabling it to create intricate and complex drawings that were unprecedented at the time. Using this drawing arm, Verostko was one of the first artists to incorporate brushwork in his computer-generated drawings. He named his software Hodos, which means "path" in Greek, a reference to the methodical way the strokes follow paths determined by the underlying chaotic system. Using this tool, he created several series, such as "Pathway", an exploration of abstract forms plotted by a multi-pen plotter driven by his software. We are excited to feature a few of his early works from the 1980s in this article.

By the 1990s, cybernetics had become firmly entrenched in the industrial landscape of the Western world. Advancements in technology brought about new terminology and interpretations, rendering some fundamental cybernetic concepts outdated. Nonetheless, it would have been beneficial for the “Automat und Mensch” exhibition to showcase artworks and narratives that acknowledge the broader societal and cultural contexts in which AI art has developed. For instance, consider the early pioneer of AI art, Lynn Hershman Leeson, whose interactive installation "Shadow Stalker" (2018–21) employs algorithms, performance, and projections to highlight the biases inherent in private systems like predictive policing, increasingly utilized by law enforcement or “Agent Ruby”, a female chatbot whose mood could be influenced by Web traffic day.

From the conceptual reflections of early AI pioneers to the practical applications of machine learning algorithms, the relationship between AI and art has undergone a remarkable evolution. It started in a lively and experimental environment, where artists and technologists went on a journey to discover the hidden possibilities of computer creativity which led to a mass adaption of open-source AI models, Chats, and generative art by 2024.

“The shift from a mechanical to an information society demands new communication processes, new visual and verbal languages, and new relationships of education, practice, and production.” – Muriel Cooper, Director MIT Press, Founder MIT’s Visual Language Workshop from 1975 (MIT LAB later from 1985).

Casey Reas, Ben Fry, Jared S. Tarbell & Manoloide.

What all the above names have in common?

“I have ideas about how software tools can be improved for myself and communities of other creators. I want to be a part of creating a future that I have experienced only in fits and starts in the recent past and present. I have seen independent creators build local and networked communities to share intellectual resources and tools.” - Casey Reas

The rapid development of computer technology in the late 20th century provided artists with new tools and capabilities to explore complex systems and patterns, creating artworks that reflected intricate interactions between programmed logic and random elements. The introduction of Processing in the early 2000s marked a pivotal moment, revolutionizing the production and proliferation of generative art.

Founded by Ben Fry and Casey Reas in the spring of 2001, Processing democratized the creation of generative art, making it accessible to anyone with a computer. In 2012, they, along with Dan Shiffman, established the Processing Foundation. This platform eliminated the need for expensive hardware and extensive programming knowledge, enabling more people to create art through code. Processing is an example of a free, open, and modular software system with a focus on collaboration and community. Processing's influence on an entire generation of artists and programmers is immense, transforming data visualization and generative art. In 2003, Jared S. Tarbell began using Processing to create engaging generative artworks that stood out both conceptually and visually. One of his most iconic works, "Substrate", showcases the brilliance of a simple algorithm: lines grow in a specific direction until they reach the domain's boundary or collide with another line.

When a line stops, it spawns at least one new line perpendicular to it at an arbitrary position. Recreating the city-like structures of "Substrate" is a fascinating exercise. From Tarbell, we can learn three key things: the value of the algorithms he shared, an artistic and exploratory approach to uncovering possibilities in code, and that profound and unexpected results can emerge from following simple rules. We are excited to showcase Substrate Subcenter2024 by Jared S. Tarbell at Kate Vass Galerie.

“A line is a do that goes for a walk” - Autoglyths by John Watkinson & Matt Hall, kleee02 by Johannes Gees & Kelian Maissen.

The introduction of blockchain technology and the founding of Ethereum in 2017 marked another revolutionary shift, impacting not only generative and AI art but also transforming the traditional art market, unleashing the power of community to drive creativity in unprecedented ways.

One of the most iconic projects, “Autoglyphs” by John Watkinson and Matt Hall, debuted at the “Automat und Mensch” show in 2019. As fine art works, “Autoglyphs” are now celebrated as the first on-chain generative art on the Ethereum blockchain. This collection of 512 unique outputs has become a highly coveted set for generative art collectors. Matt and John, enthusiasts of early generative art, have drawn inspiration from the 1960s aesthetic and experimented with the computing and storage challenges faced by pioneers like Michael Noll and Ken Knowlton. Their work reflects a deep respect for the origins of generative art while pushing its boundaries.

Ken Knowlton, from the pages of Design Quarterly 66/67, Bell Telephone Labs computer graphics research

Another lesser-known project, “kleee02”, was launched around the same time in Switzerland. It was an unfortunate oversight not to include it in our show. “kleee02”, an art piece by Kelian Maissen and Johannes Gees, had its smart contract verified in April 2019, the same week as “Autoglyphs”. This work offers a contemporary, blockchain-inspired take on conceptual art, inspired by Swiss artist Paul Klee’s famous quote, “A line is a dot that goes for a walk”. The "walk of the dot" is detailed in the “kleee02” smart contract, with each of the 360 non-fungible tokens (NFTs) being unique in shape and color. Uploaded to the Ethereum blockchain on April 10, 2019, “kleee02” emerged as a pioneering project that could have been featured in the "Automat und Mensch" show in May 2019. The project was officially launched on June 3, 2019, with a public laser projection of the first minted NFTs at Johannes’s studio in a park near Zurich, Switzerland.

Since then, the adoption of blockchain, the launch of ArtBlocks in November 2020, and the foundation of so-called “long-form generative” art have transformed the entire landscape of ownership and value. These innovations have enabled the community to better understand and collect generative art as NFTs, fostering a new era of digital creativity for the next five years.

Alex Mordvintsev, Robbie Barrat, Mario Klingemann, and Helena Sarin.

The past five years have witnessed a dramatic leap in AI capabilities, ushering in an era of unprecedented innovation in artistic expression. Deep learning algorithms, Mid Journey, Stable Diffusion, Dall-E, ChatGPT and other open-source models have revolutionized the creative process, enabling artists to transcend traditional boundaries and explore new frontiers of imagination. Nevertheless, we see a set of trends that after the spike of newer tools, the attention of collectors returns to the earlier AI generation, predominantly GANs (generative adversarial networks) artworks, concept based on neural networks that computer scientist Ian Goodfellow introduced in 2014. The greatest attention is also given to contemporary early AI creators such as Mario Klingemann, Robbie Barrat, David Young, Gene Kogan, Memo Akten, Helena Sarin and more, who have been working with AI for decades.

Alexander Mordvintsev, Custard Apple, 2015

Alexander Mordvintsev, Whatever you see there, make more of it!, 2015

One of the earliest and most influential works in this field was created by Alexander Mordvintsev, the inventor of Google DeepDream. Released as open source only in July 2015, DeepDream mesmerized audiences with its psychedelic and surreal imagery. Nearly all contemporary AI artists attribute Mordvintsev's DeepDream as a major source of inspiration for their exploration of machine learning in art. While one of the initial images generated by DeepDream was showcased at the 2019 “Automat und Mensch” exhibition, it was not offered for sale and was displayed as a small physical print.

After DeepDream, many artists began experimenting with incorporating AI technologies, particularly machine learning and neural networks, into their art. One such artist, Robbie Barrat, created works like “Correction after Peter Paul Rubens, Saturn Devouring his Son” (2019), which have gained increased significance from a historical perspective. Robbie Barrat, who was just 19 in 2019, displayed various artworks at “Automat und Mensch”. This piece exemplifies how technology can be harnessed for creative exploration, showcasing the potential of AI in art. Since 2018, Robbie has been collaborating with French painter Ronan Barrot, exploring AI as an artistic tool. "Correction after Peter Paul Rubens, Saturn Devouring his Son" is influenced by Ronan's technique of covering and repainting unsatisfactory parts of his work. Robbie applied this concept to AI by teaching a neural network to repeatedly obscure and reconstruct areas of nude portraits. This process, known as inpainting, aligns the painting with the AI's internal representation, often resulting in a completely transformed image. The term "correction" here reveals the AI's interpretation of the nude body, not an attempt to improve the original works.

In another notable project, "Neural Network Balenciaga”, Robbie Barrat used fashion images to train his AI model. In a 2019 interview with Jason Bailey, Barrat explained that he combined Pix2Pix technology with DensePose to map the new AI-generated outfits onto models, crediting another established artist, Mario Klingemann, for developing the DensePose + Pix2Pix method.

Mario Klingemann, who won the Lumen Prize in 2018 and had his work auctioned at Sotheby’s in 2019, was one of the known artists featured in the show for his work “Butcher's Son”. Mario continues to produce visually fresh and refined art, experimenting with different technologies, whether using GANs or other tools. His unique artistic style is consistent, recognizable, conceptual, and experimental.

As AI technology becomes more widely accessible, the distinction between exceptional AI artists and those who merely repurpose old work or simplify image creation by pushing the button relies increasingly on vision, fresh ideas, and later innovation. Helena Sarin, for instance, one of the key figures in the AI scene, has maintained her unique style and tools over the last five years, creating art, books and pottery that stand out stylistically among the rest. Her practice underscores the significance of artistry and dedication to the original creativity. Helena Sarin's ethereal compositions, infused with a sense of wonder and mystery, continue to captivate audiences with their poetic resonance. “They don’t do GANs like this anymore” captures the essence of today’s AI art scene.

Conclusion

While there is a current upswing in interest in AI art, it's difficult to predict whether this trend will continue or if a correction is on the horizon. Nonetheless, digital art undeniably holds a significant and dynamic position in the contemporary art landscape.

Debates about whether AI will dominate the world or if human creativity will diminish in the coming decades are pressing questions of our time. Since the term "artificial intelligence" was coined in the 1950s at the Dartmouth conference, the pursuit of creating artificial general intelligence has been ongoing. Despite this, the concept of "intelligence" remains elusive. Algorithms, while capable of operating independently, do not match the general intelligence of the human mind.

AI saw significant progress with early systems like ELIZA up until the late 1970s. However, by the early 1980s, interest and funding began to wane, contributing to periods commonly referred to as the AI winters. AI winter reflects a general decline in enthusiasm that paralleled cultural milestones like the release of the original “Blade Runner” in 1982.

Could another AI winter follow the current surge of interest, since we have similar trends in 2020s with multiple wars, economic distress, and world political instability? Initially, technology was intended to support and extend liberal democracy after the Cold War. However, recent developments suggest it might be on the brink of instigating a new era of conflict.

The relationship between human and artificial intelligence might cool for various reasons. If the clash between human and artificial intellect collapses into neglect, another AI winter could ensue. Alternatively, the substantial financial and human investment in AI thus far could lead to a prolonged struggle, potentially triggering a "cold war" with intelligent algorithms too, couldn’t it?

Art, however, has proven to endure and evolve over the past 80 years. We believe that in the next 80 years, some current pioneers will be recognized as cultural icons in the history of generative and AI art. As life progresses, we innovate, trends change, and artists continue to create. Despite these advancements, we have yet to develop “general superintelligence” capable of creating independently from human influence and input.

Le Random has released an exclusive interview with Jason Bailey, Georg Bak, and Kate Vass to highlight the show on its 5th anniversary. Read the full article by clicking the button below.