Herbert W. Franke : Border-crosser between Science and Art

We want to offer our English-speaking readers an opportunity to enjoy the most recent interview by Peter Tepe with one of the pioneers of generative art - Herbert W Franke. This article Part 1 was published in Zwischen Wissenschaft & Kunst in April 2020 and only available in German. The second part of this interview will be coming soon, and will be published in English in our next editorial Ed. XII ‘Collecting generative art’

w/k – Zwischen Wissenschaft & Kunst addresses everyone interested in the interfaces between science and art – and especially artists, scientists and curators who deal with this topic professionally.

We hope you enjoy reading this insightful interview from the living legend of generative art Herbert W Franke!

Herbert W. Franke: Border-crosser between Science and Art

April 24, 2020

A conversation with Peter Tepe | Summary

Herbert W. Franke is in many ways a border-crosser between science and art: He is a scientist (a physicist and speleologist), artist (in the visual arts and as an author) and art theorist – a case of particular interest to w/k. Part 1 of the interview focuses on the scientist and the visual artist. Part 2 will follow in the coming months.

Bühnenbild zu H.W. Franke: Kristallplanet (2019). Foto: Marionettentheater Bad Tölz.

PT: Herbert W. Franke, you are a border crosser between science and art. w/k has a special interest in such individuals. Your scientific fields of activity include physics and speleology. In the visual arts, you are a pioneer of algorithmic art, the special nature of which we will explain below. In addition, you have published texts on the subject of "art and science," such as Phänomen Kunst (Heinz Moos Verlag, Munich 1967). At the same time, you have published other books on the theory of art, e.g. Computergraphics - Computer Art (Julius Springer Verlag, Heidelberg, Berlin, New York, 1985). Another important field of your work is Science Fiction literature. You are now 92 years old. In which of the above-mentioned fields are you still active?

HWF: At the age of 92, productivity has naturally diminished somewhat. But I am still active today: I write science fiction stories or program pictures on my PC. Again and again I also give readings, for example always before the performance of the puppet play I wrote, The Crystal Planet.

PT: In order to shed more light on your individual connections between science and art, it would be useful to begin with a brief biographical outline.

HWF:After receiving my doctorate in physics from the University of Vienna in 1950, I would have been very happy to accept a position at the university's Radium Institute, in order to confirm experimentally my theoretical work on the form record of stalactites and the connection with the paleoclimate. Paleoclimate is the term used to describe the climate in the past and how it developed over periods of hundreds of thousands of years. Unfortunately, however, there was no research possibility for me in Austria shortly after the war, because the institutes were not yet equipped with the necessary instruments.

So in 1952 I went to Germany, the land of the economic miracle, and took a position with Siemens & Halske in the advertising department. After I left the company at my own request in 1957, I began my freelance work as a publicist. I not only wrote popular technical articles and books, but also published literary books starting in 1960.

Already during my time at Siemens, I began artistic experiments in the photo lab. In 1959 I was able to realize my first solo exhibition at the Museum of Applied Art in Vienna. In addition to artistic performances, there was also extensive exhibition activity. I not only exhibited my own works, but also curated numerous exhibitions and events on computer art, including a Goethe-Institut exhibition shown in more than two hundred countries. At Ars Electonica I was one of the founding fathers. At the University of Munich I taught Cybernetic Aesthetics from 1973 to 1997, later Computer Graphics - Computer Art. From 1984 to 1998 I also had teaching assignments at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, also on computer art.

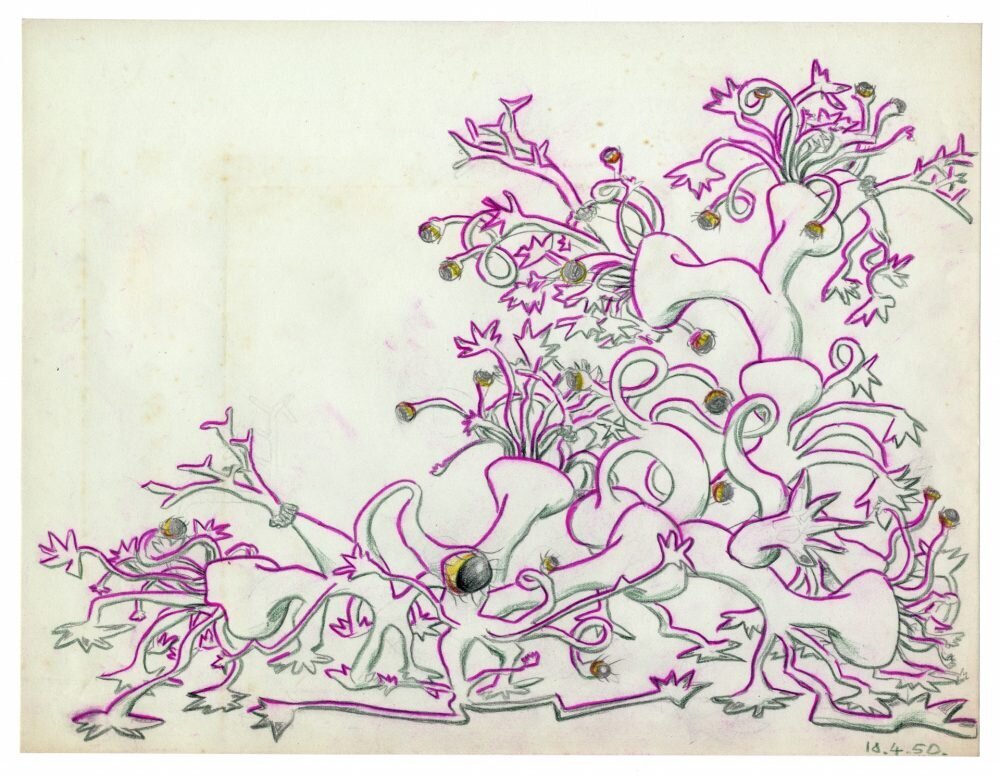

H.W. Franke: Jugendzeichnung (1945). Foto: Bildarchiv space press.

PT: How did the connection between science and art in general and visual art in particular develop in your case?

HWF: When I was a physics student in Vienna after the war, I was also active artistically on the side: I photographed landscapes and in caves, but also drew and wrote stories. However, I never thought of becoming an artist. At that time, I was already interested in aesthetics and art theory: I asked myself why we find some images from science beautiful. I saw myself above all as a scientist who always wanted to get to the bottom of things, to understand them.

H.W. Franke: Höhlenfotografie (1975). Foto: Bildarchiv space press.

PT: How did your artistic activities become independent?

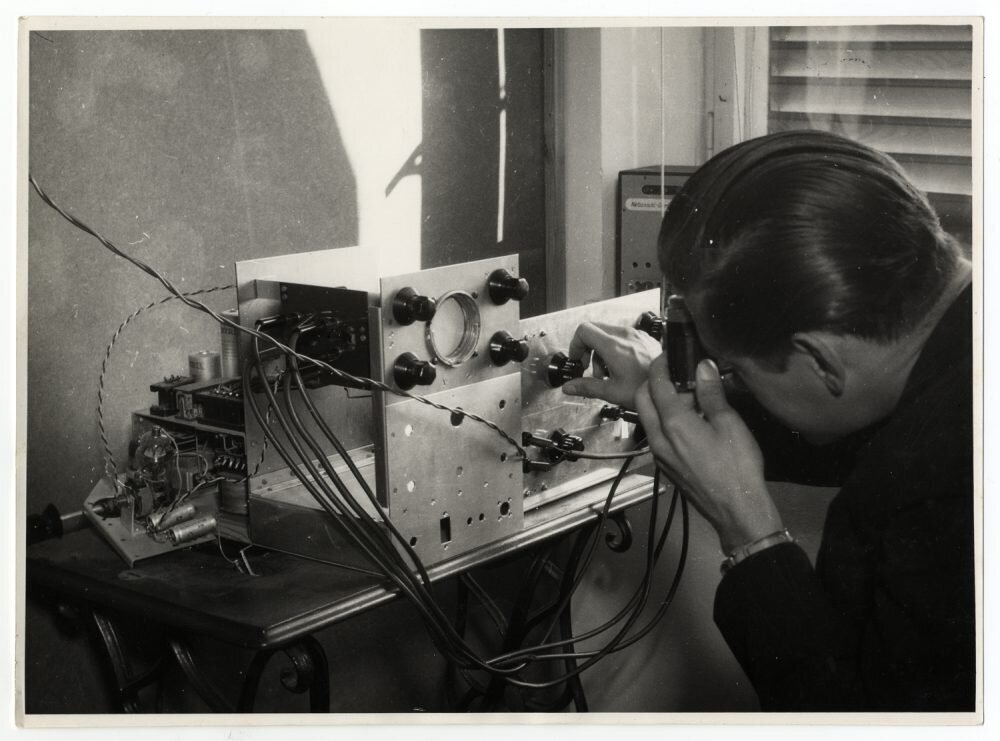

Der von H.W. Franke für die Serie Oszillogramm verwendete Analogrechner(1953). Foto: Bildarchiv space press.

HWF: I started writing because during my studies at the end of the 1940s I came into contact with Neue Wege, a respected cultural magazine in post-war Austria. The editor-in-chief, to whom I had sent poems, did not accept them, but asked me if I, as a physicist, would like to write articles for the magazine about new developments and future prospects in science and technology. I gladly accepted the offer, of course. Incidentally, my first science fiction short story also appeared in Neue Wegen in 1953. And even some of my poems were later printed in it!

PT: We will deal with the science fiction author Herbert W. Franke in more detail only in Part II. At this point we are interested in the beginning of your activities in the field of visual arts. In the beginning there was photography, if I am informed correctly.

HWF: That is correct. My photo-artistic activities began, as I said, as early as 1952 during my time at Siemens. There I got the opportunity to experiment in the photo lab.

PT: What kind of photo experiments were they?

HWF: I am talking about generative photo experiments.

PT: What is meant by this?

HWF: In contrast to depictive photography, this is the realisation of abstract pictorial ideas - if you like: visual inventions that show forms and structures that are not already there, but are only created or made visible through special technical means. I experimented with very different methods. In contrast to the light graphic artists of the 1920s, I was interested in images that were created in a systematic way, under defined conditions. Physical phenomena include, for example, oscillations and vibrations as well as deformations under the influence of elasticity, and finally Moiré effects, i.e. superimpositions of line structures. Or take the group of works of analogue graphics: Here I generated images on an oscilloscope with the analogue computer a friend had made, which I then photographed with a moving photo camera with the aperture open.

PT: What happened next?

HWF: At the end of the 1950s, when I had already been working as a photographic artist for several years, I came into contact with the art historian Franz Roh, who admonished me that I "had to take my work seriously" - it could lead into new artistic territory. I also owe the publication of my first book Art and Construction in 1959 to his support. Incidentally, Roh's admonition was also the reason that I soon felt encouraged to call my work art, despite considerable resistance from the established scene.

PT: Can you distinguish between several phases in your artistic development after the beginnings you've described?

HWF: Yes, of course - and they were closely linked to the development of computers after my photographic experiments. For with the advent of mainframe computers, I quickly switched from analog to digital technology. However, these machines were only located in large research laboratories of universities or corporations. In the 1960s and 1970s, it wasn't easy to get access to them for artistic experiments if you didn't have access to such machines through your employment - either in research or in industry. My old contacts to the research laboratories in the Siemens Group also helped me. Incidentally, for my first digital images ever - the series is called Squares - I was allowed to use a mainframe computer at the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry in 1967. This phase was actually never completed, because again and again I had the opportunity to misuse mainframes for artistic purposes. Possibly the fact that I didn't have access to just one particular mainframe like other pioneers, but was always on the lookout for new computers, was also an advantage. Even back then, I was able to experiment with very different software on different operating systems.

H.W. Franke: Quadrate (1967). Foto: Bildarchiv space press.

PT: What artistic goals were you pursuing in Phase 2?

HWF: Actually, it was always about one major goal that runs like a thread through my artistic activities: namely, to examine machines for their creative potential applications. For me, it wasn't about the picture on the wall. From the very beginning, I was also looking for new ways in design, which I associated with concepts such as dynamics and interaction. For the visual arts, I was looking for something comparable to a musical instrument - and was convinced that the computer would point the way. Thus, as early as 1974, I made a computer film; during this period, I used other photo series created with mainframes to achieve a dynamic effect by superimposing serial motifs.

PT: Now to phase 3.

HWF: It began in 1979: First of all, in that year I had the opportunity to develop a program for one of the first small computers, the TI 99/4 from the company Texas Instruments - similar to the famous Amiga. It was supposed to give people the opportunity to experiment artistically with images. There was also an automatic mode, where the program MONDRIAN, by the way, generated sound effects to the pictures. Of course, the program did not sell. But as far as I know, it is the first interactive and dynamically running artistic program for images and music ever. Still at Texas Instruments (TI), I had to record the algorithms manually as a flow chart. It was then converted into the company's own software by a TI programmer. But in the same year I was able to start programming myself, because at the end of the 1970s the first apple II came on the market, which of course I bought immediately. Not much later, I also bought an apple GS, where GS stands for graphics and sound, before I switched to the DOS world of Microsoft in the mid-1980s. As with the TI 99/4, I was interested in the artistic design of dynamic and interactive graphics programmes on my own PCs - also and especially with regard to the control of dynamic images with music. For the first time, I was able to program myself during this phase - at first I used Basic, a simple programming language that also ran on apple. During this time, I created programmes like GRAMUS (for graphics and music) or Kaskade, a programme for music control. It fascinated me to be able to design the algorithms on the computer, see the graphic result on the screen and then modify it. What I had always dreamed of had become reality - despite all the technical limitations in computing power and graphic implementation possibilities: a machine with which one could realise artistic experiments. With the DOS computers, I switched to Quickbasic, a variant of Basic that had been developed very early on especially for graphic programming. To this day I sit at the PC and programme, but in the meantime I work a lot with the software Mathematica by Stephen Wolfram.

H.W. Franke: Serie Kaskade (1983). Fotos: Bildarchiv space press.

PT: What can be said about phase 4?

HWF: Between 1979 and 1995, I opened up a special subject: My friend Horst Helbig worked in Oberpfaffenhofen at the then German Research and Testing Institute for Aeronautics and Astronautics (DFVLR), now renamed the German Aerospace Center (DLR), as a programmer for the evaluation of satellite images. At weekends, we were allowed to use the computer system developed by DLR, which filled two rooms, for private experiments. During this time, an extensive collection of images was created. This subset of my algorithmic art, in which I explicitly deal with the visualisation and aesthetics of mathematical formulae and structures, is what I now call Math Art. At that time, Benoit Mandelbrodt's apple men were well-known, but we also examined numerous other mathematical formulae and logical functions for their aesthetic dimension, for example complex numbers. The subject still occupies me today, although I no longer need a mainframe computer for it. At the end of the 1990s, as I mentioned earlier, I got into the programming language Mathematica, which was used to create interactive programmes like Wavelets or Slings. It allowed me to experiment with such mathematical functions at home on my own PC.

This phase also includes my experiments with the cellular automata introduced by Stephen Wolfram, a special topic of game theory for modelling dynamic systems, which are very important today in research into artificial intelligence, for example. I myself used them to investigate the effect of random generators in such models. These world models that change over time are not only scientifically exciting, the visualised simulations also show aesthetically highly interesting results. As a physicist, I am very much moved by the philosophical question of what significance chance has in our world - for example, in relation to whether this world freezes, ends in chaos or runs infinitely - and to what extent we live in a deterministic universe or one that is also controlled by genuine random processes.

PT: Now we come to the last phase 5 for the time being.

HWF: You mean the Z Galaxy. I don't know if the term "phase" is appropriate at all. Z stands for Konrad Zuse, the inventor of the modern computer. I have been building the Z-Galaxy in a virtual world since 2009. The platform is called Active Worlds. The world I create in it is a kind of virtual exhibition site through which you can wander as an avatar. In halls you can see changing motifs of some of my works, but you can also view art by some of my friends.

H.W. Franke: Z-Galaxy (2009). Foto: Bidarchiv space press.

PT: We have thus presented the visual artist Herbert W. Franke quite broadly. It has also become clear that you are - to use the w/k terminology - in all phases a scientifically working artist, i.e. an artist who draws on scientific theories/methods/results.

HWF: I fully agree with this classification.

PT: Now we turn to address you as a physicist. In our questionnaire for border crossers between science and fine arts, it says: "Each border crosser is first asked to briefly present his or her scientific work in a generally understandable way; for example, the physicist who is also an artist explains what he or she does as a physicist." In the course of your development as a physicist, what were the most important areas of work, and what did you do there?

Höhlentour von H.W. Franke in der Weißen Wüste (2006). Foto: space press.

HWF: My dissertation in theoretical physics was on a topic in electron optics, specifically the calculation of electric-magnetic fields used, for example, as lens systems for scientific instruments such as electron microscopes or mass spectrometers. However, the later focus of my scientific work was in speleology. What began as a hobby quickly interested me as a physicist as well: the geological formation of cave spaces and dripstones. How do they form, and how can their age be determined? In the 1950s and 1960s, these were questions that science could not answer unambiguously - and so it appealed to me to look into these processes and answer the questions. In addition to this theoretical work, I participated in numerous scientific expeditions, especially in the European Alps. For example, in 1975, on behalf of the German Research Foundation, I was able to participate in a caving expedition at the University of Jerusalem in Israel. It was one of the earliest projects to clarify the connection between the Central European glaciation periods and the climatic consequences in the desert areas around the Mediterranean. Much later, around the turn of the millennium, I participated in several research trips to the Sahara. There, in a region called the White Desert, we found remains of very old cave structures. They date back to a time about ten thousand years ago, when a humid and fertile climate still prevailed in this region after the last ice age, and thus dripstones could be formed.

PT: As a physicist, have you worked entirely within the framework of the respective state of research achieved or are there also fields of work in which you have found out something new? If so, please explain these innovations.

HWF: I think the special thing about my work is the crossing of boundaries: for example, that the development of a physical method for determining the age of dripstones can provide an important insight on the way to understanding the development of the Earth's climate since the Ice Age. Together with Mebus Geyh, I have also used the new method of determining the age of dripstones, which I presented theoretically for the first time, for geochronology - i.e. not only in research into the formation of caves, but also in another field of research, palaeoclimatology. There, this method has been used to date warm periods in the last ice age and also to determine their end. Another example: Back in 1998, I was the first to write a theoretical paper on the existence of volcanic caves on Mars. When I published it, many of the experts in the field of planetary research were still quite sceptical. But that's exactly what makes border crossers: they look beyond the horizon of their expertise. By the way, in the meantime probes have observed collapse holes on Mars that can only be explained by the existence of such cave systems.

PT: Herbert W. Franke, thank you for the insightful conversation, which we will continue shortly.

Contributing image above the text: H.W. Franke (2017). Photo: space press.

to Youtube channel by Herbert W. Franke

http://www.herbert-w-franke.de