MORPHING BEYOND THE SURFACE: THE ART OF NANCY BURSON'S DIGITAL PORTRAITURE

Nancy Burson is an American artist and photographer born in 1948. She is best known for her pioneering work in computer morphing technology and is considered to be the first artist to apply digital technology to the genre of photographic portraiture. Utilizing the morphing effects she developed while she was at MIT, Burson has incorporated these techniques in various ways throughout her career including age-enhancing techniques, the creation of composite portraits, and the development of race-related works. Many people may recognize some of her creations, even if they aren’t familiar with her name. Some of her most recognizable works include the digitally morphed “Trump/Putin” on the cover of Time magazine, and the updates of missing children's portraits on milk cartons.

We can see her art in museums and galleries such as the MoMA, Metropolitan Museum, Whitney Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Center Pompidou in Paris, the LA County Museum of Art, and the Getty Museum among others. She was a visiting professor at Harvard and a member of the adjunct photography faculty at NYU for five years.

In this article, we will focus on Burson's morphing technique, presenting how she used this technology in different ways throughout her career. We will showcase her works and discuss why her art is important in the history of digital art and portrait photography. This article will include an exclusive interview with Nancy Burson herself. Burson shares her inspirations and the creative process behind her work, as well as discusses her past and personal reflections on her art with Kate Vass.

Morphing technology

Motion pictures and animations often use morphing techniques to create a seamless transition between two images. It is a geometric interpolation technique that has been around for a long time, with traditional methods like tabula scalata and mechanical transformations. Besides these techniques, probably the most effective way to morph images was through “dissolving”, which was developed in the 19th century. Dissolving is a gradual transition from one projected image to another, for instance, a landscape dissolving from day to night. This technique was groundbreaking in the 19th—early 20th century, proving the potential of visual effects in motion pictures.

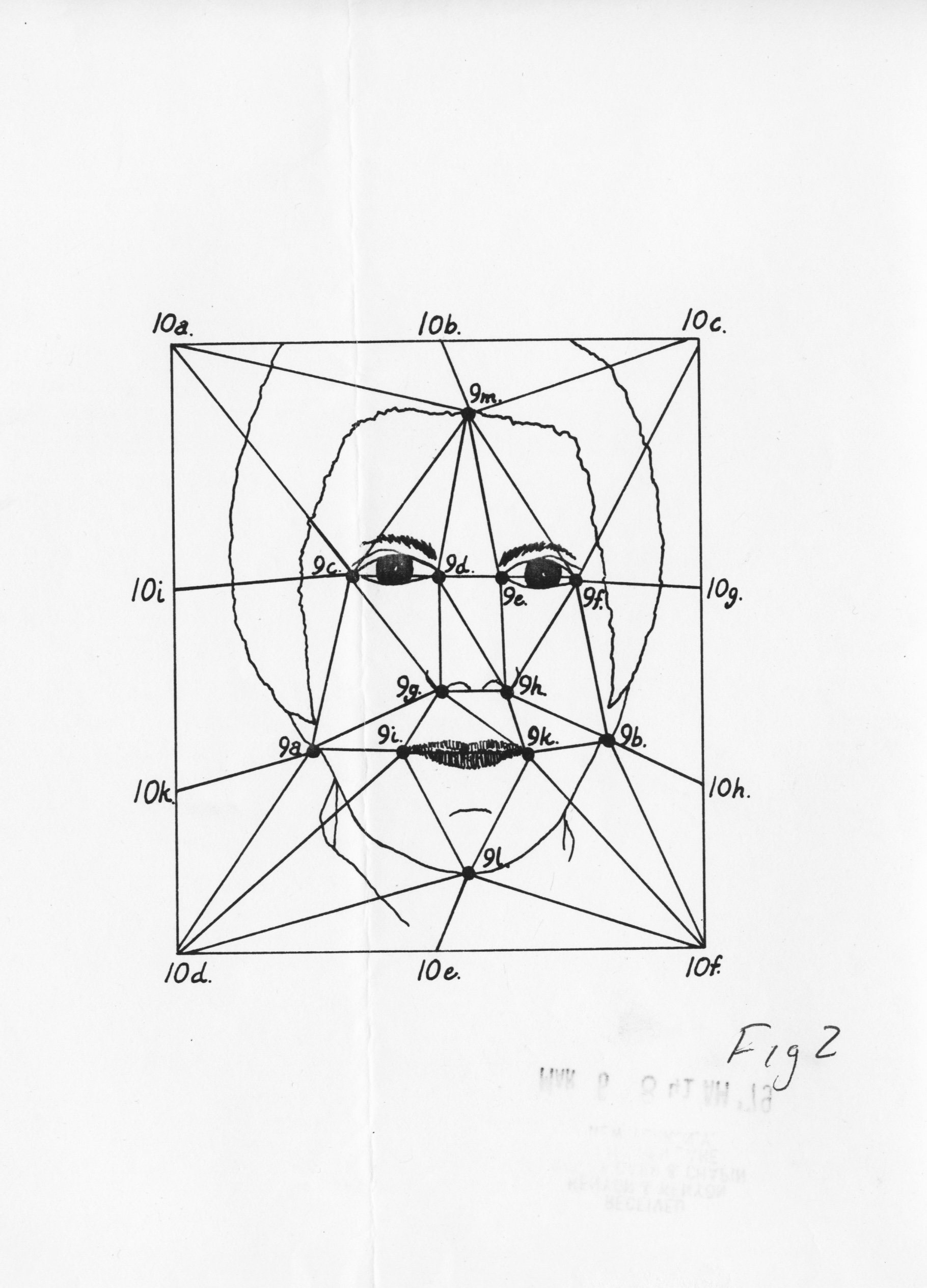

Computers replaced dissolving since the 1980s and have made morphing more convincing than ever before. Digital morphing involves distorting one image at the same time as it fades into another by making corresponding points and vectors on the before and after images. For example, we can mark key points on a face, such as the corners of the nose or the location of the eyes, and also mark these points in the second picture. The computer then distorts the first face to match the shape of the second face while gradually blending the two.

One of the first companies that used digital morphing techniques was the computer graphics firm, Omnibus. It used this technique first for commercials and then for movies. It contributed to a film called "Flight of the Navigator" which featured scenes with a computer-generated spaceship that appeared to change it’s shape. Bob Hoffman and Bill Creber were the developers of that software. Later, morphing techniques have mainly been used in the film industry. Morphs appeared in movies like “Willow” (1988), “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” (1989), and “Terminator 2: Judgment Day” (1991). In 1992, Gryphon Software developed the first morphing software, called MORPH, designed exclusively for personal computers.

Morphing Technology in Art

Nancy Burson is widely regarded as the first artist to use digital technology to create composite portraits in the early 1980s. However, prior to this, composite images were created through analog techniques by overlaying multiple images to blend and create a single image. Artists like Francis Galton and William Wegman made significant strides toward analog composite images before the arrival of digital technology.

In the 1870’s, Francis Galton first applied compositing techniques for the purpose of visualizing different human “types”. He tried to determine whether specific facial features could be associated with distinct types of criminality. Galton used multiple exposures to create composite photographs of different segments of the population, including mentally ill and tuberculosis patients as well as what he regarded as the "healthy and talented" classes, such as Anglican ministers and doctors.

Later, William Wegman continued this tradition by creating composite images in his artistic practice in 1972. His piece, "Family Combination" compared a photograph of himself with the genetic combination of his parents. He used two negatives simultaneously, one of his mother and one of his father, to create one image.

Nancy Burson: “I remember seeing Wegman’s Family Combinations when I was already working with MIT. And I didn’t find out about Galton until I was already making my own composites. It was a shock in that Galton was responsible for Eugenics, or the science of you are what you look like. I was horrified at the thought of anyone thinking that my composites were done with the same line of racist thinking. However, when they were first shown at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in 1985, it did seem that people understood my images had a light heartedness to them.”

Nancy Burson’s development

St. Louis-born Nancy Burson moved to New York in 1968. She visited the exhibition, "The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age" at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which made a tremendous impact on her life. The exhibition featured moving objects and video images, which sparked Nancy's interest in technology.

N.B.: “What I liked best about the Machine show at MoMA was that some of the pieces were interactive. The idea that viewers could participate in the art was huge and quite memorable for me. It turned the museum into a fun experience and not just a cultural one. The pieces that stuck with me the most were Nam June Paik’s videos presented in what I remember as dark cases. I remember that after seeing that exhibition, I began to visualize in my mind an interactive age machine in which viewers could see themselves older. I knew nothing at all about computers so I knew I’d have to find the people who did!

I grew up with a science background. My mother was a lab technician and my favorite memories of my childhood were of doing fake experiments with real blood! I put everything I could under my brother’s microscope!”

Nancy met early computer graphics consultants through artist’s Robert Rauschenberg’s (known for his collages that incorporate everyday materials) and Billy Klüver's (video artist) organization, Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT). Rauschenberg and Klüver had worked together with scientists to organize the “9 Evenings” performances that took place at the 69th Regiment Armory in NYC in 1966. They established the non-profit EAT that same year. EAT was pairing artists together with scientists and Nancy was paired with an early graphics specialist who informed her the technology to produce aged images was years in the future. In the interim, Burson turned to painting and in 1976, it was suggested she contact Nicholas Negroponte, the head of MIT’s Architecture Machine Group, later called The Media Lab. They had just hooked up a camera to a computer which was an early version of a digitizer or scanner. It was one of the first times that a computer interacted with a live version of a face. It took five minutes to scan a live face and subjects had to lie underneath the copy stand and be told when they could blink.

The set up at MIT which was their first version of a digitizer

Originally, she thought her idea would only be useful beyond an art context for its potential usage in cinematic special effects. However, she soon realized that the technology she developed was more useful than she initially thought. By 1981, Nancy was issued a patent for her aging machine, “The Method and Apparatus for Producing an Image of a Person’s Face at a Different Age.”

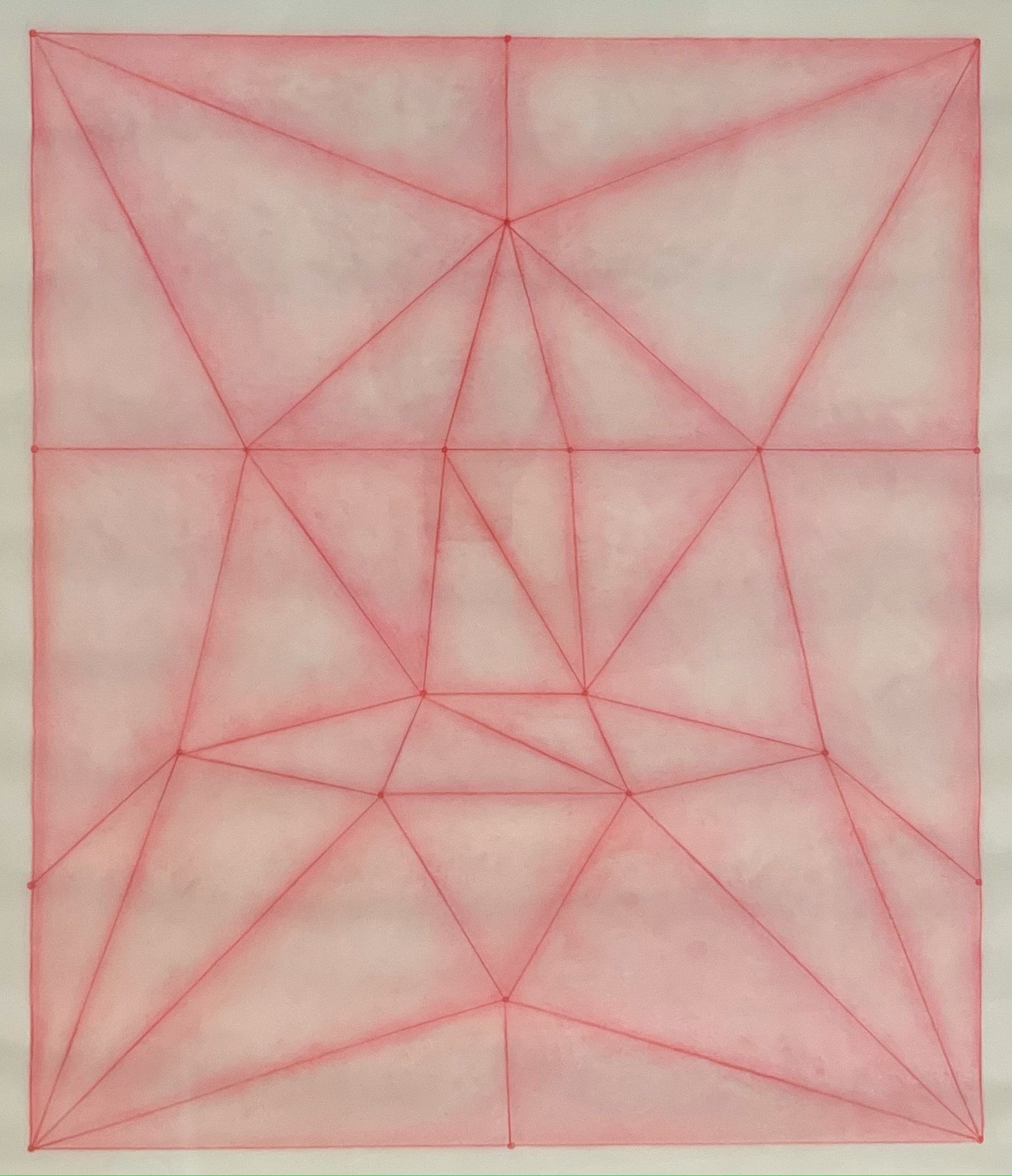

N.B.: “In my initial meetings with MIT, I was paired with a collaborator, Thomas Schneider. The project was dubbed ATE, an homage to its first beginnings from EAT. It was Tom’s design for the triangular grid which still remains the standard morphing grid in the industry today for everything from sophisticated AI software to SnapChat. When I left MIT in 1978, Tom and I became co-inventors, and he turned over his rights to me. In 1979, I was invited to present my initial video of three faces aging that were the result of my work with MIT at the annual SIGGRAPH computer graphics conference. It was that conference that first exposed the new facial morphing technologies to everyone who was to become anyone in the industry, including those who became the graphics specialists at Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) and Pixar films.

Through my former colleagues at MIT, I continued my work with two computer graphics specialists working for Computer Corporation of America, Richard Carling and David Kramlich. We fashioned our early morphing sequences into funny video presentations that were shown in the SIGGRAPH film shows in 1983 and 1984, further exposing the technology to everyone in the industry. And it was Richard, David, and I who collaborated on my first book called Composites: Computer-Generated Portraits published in 1986.”

Early works (1976–1999)

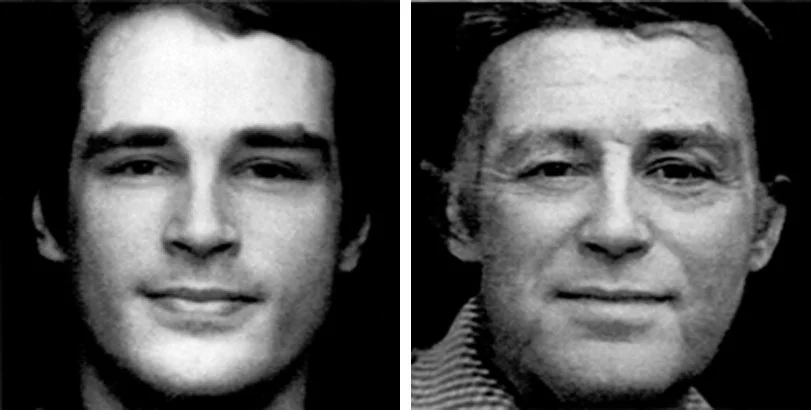

To facilitate the development of the software being built by MIT from 1976 to 1978, Burson created a self-portrait series, “Five Self-portraits at Ages 18, 30, 45, 60, and 70” in which she documented her own future aging process. She collaborated with a makeup artist to transform her face using make up to the ages of 18, 30, 45, 60, and 70. It was that study that informed how the software would enable her to explore the methodologies of altering and manipulating human features. Through the 1980s, she also used digital technology to blend the faces of groups of individuals to produce Composite Portraits.

Burson often digitally combined and manipulated images of well-known individuals, such as famous politicians and celebrities. Through these images, Burson investigated political issues, gender, race, and standards of beauty. She created one of her most important works, “Warhead I” (1982), by using images of five world leaders—Ronald Reagan, Brezhnev, Margaret Thatcher, François Mitterrand, and Deng Xiaoping—proportionally weighting the image by the number of nuclear warheads deployable by the nation they led.

Burson also examined the concept of beauty in our society. In one of the first composites made in 1982, she creatied composite portraits that were a comparison of styles between the 1950’s and the 1980’s, exploring how beauty is defined in our society. For example, her "First Beauty Composite" (1982) featured the faces of Bette Davis, Audrey Hepburn, Grace Kelly, Sophia Loren, and Marilyn Monroe. And her "Second Beauty Composite" (1982) featured images of Meryl Streep, Brooke Shields, Jane Fonda, Diane Keaton, and Jacqueline Bisset.

She also explored other themes through her composite portraits. Her "10 Businessmen From Goldman Sachs" (1982) was a blend of 10 businessmen from that firm, while her "First and Second Male Movie Star Composites" blended images of movie stars in yet another style comparison. The "Big Brother" image produced in 1983, was a mix of the faces of political figures Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, Mao, and Khomeini for a CBS TV special that recreated George Orwell’s Big Brother from his novel 1984.

The process of morphing faces was not only time-consuming but also required a considerable amount of skill and effort in its early days.

N.B.: “In 1982, the process that we used to morph faces was different in that we would overlay all the images on the eyes and ascertain an average. Then we would warp, or morph, each face to fit the average. It took 25 minutes to scan a face and morph it to the average face and then we’d combine them all together. It was an incredibly tedious process. Nowadays, there are some great programs available online which morph faces together and can weight them in different percentages as well.”

One of Nancy Burson’s most important works is the “Age Machine”, which utilized her patented technology of 1981, “The Method and Apparatus for Producing an Image of a Person’s Face at a Different Age.”

The “Age Machine” was an interactive installation that simulated the aging process, offering a glimpse into what viewers might look like in the future. The installation scanned the face, and the viewer interactively moved data points for their features (ends of eyes, nose, mouth etc.). Then the software applied an aging template that corresponded to the viewer’s facial structure. Over the years, David Kramlich increased the speed of the process from 25 minutes to just a few seconds making it possible for viewers to be active participants within the museum experience. Quickly garnering attention for its boundary-pushing creativity, the “Age Machine” used cutting-edge technology to delve into questions surrounding identity and aging. It was shown at many important venues including the Venice Biennale in 1995 and the New Museum (NYC) in 1992.

Another variation of the initial morphing process was used by law enforcement agencies to find missing children or adults, predicting how they would look many years after their disappearance. Copies of the software were acquired by the FBI, as well as the National Center for Missing Children. By the mid 80’s, at least half a dozen children and several adults were found from Burson’s updating methodologies and collaborations with law enforcement. Through her art, Burson did what other artists only dream about. She changed people's lives.

N.B.: “I was completely unaware of the software’s potential use in finding missing children. However, in 1983, the Ron Feldman Gallery asked me into a group exhibition called “The 1984 Show”. The piece I chose to exhibit were aged images of Prince Charles and Diana with their “composite” teenage son, William. A woman with a missing child saw the show and asked me if there was anything I could do to update children’s faces. It was the true beginning of my work with missing kids. I knew the process we had been using to composite faces needed to be adjusted to update children’s faces so David Kramlich and I reworked the process. At that point, there were some Hollywood producers who came to us with a couple of serious cases of parental abductions and when they were aired on national TV, the children were found within the hour. It was wild to see the images we’d created on a computer screen come to life when those kids were found.”

Based on the same technique, Burson developed other machines as well. The “Anomaly Machine” (1993) showed viewers how they would look with a facial anomaly based of the research and data that she collected in taking portraits of real children’s faces with various craniofacial disorders. The “Couples Machine” combined two people together in whatever percentages they wanted. All these machines were offshoots of the original Couples Machine from 1989, which combined viewers’ faces with movie stars and politicians and was shown originally at the Whitney Museum.

Later works (2000 - now)

Nancy Burson, DNA HAS NO COLOR (An a/p of the glass sculpture made at Berengo Studios in Morino and acquired by the Boca Raton Museum)

Besides the above creations, there was another important artwork that was based on Nancy’s development of "The Method and Apparatus for Producing an Image of a Person's Face at a Different Age". “The Human Race Machine” was a public art project which was inspired by a meeting in the mid-1998 with one of Zaha Hadid's staff and was launched at the Mind Zone in the London Millennium Dome on January 1st, 2000. It was the perfect backdrop for the project which was an immense success with long queues of visitors waiting for hours. “The Human Race Machine” used morphing technology to show people how they would look as a different race, including Asian, Black, Hispanic, Indian, Middle Eastern, and White. After the British launch, “The Human Race Machine” went on to be featured in diversity programs in colleges and universities across the US for over a decade. It was also featured in Burson’s traveling retrospective that began at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery in 2002, and was nominated for Best Museum Show of the Year by the American Art Critics Association.

The project provided viewers with the visual experience of being another race and perhaps helped to promote a message of unity by allowing people to experience what it’s like to be someone of a different race. Later she created several works that explore the concept of diversity and equality.

N.B.: “In 2000, I did a project for Creative Time that accompanied a group exhibition exploring DNA in which I showed the “Human Race Machine”. Accompanying the exhibition, Creative Time commissioned a billboard at Canel and Church Street that said, “There’s No Gene For Race.” I consider the “DNA HAS NO COLOR” message of these sculptures and billboard an update of that same concept. Race is merely a social construct having nothing to do with the science of genetics. In fact, our DNA is really transparent, although scientists color it so it can be seen. With the prevailing upturn in racism today, I believe “DNA HAS NO COLOR” is an even more timely message than “There’s No Gene For Race” was almost 23 years ago. We are all one race, the human one.”

Nancy Burson has always had a keen interest in political issues. In relationship to her “Human Race Machine”, she created a series of images of Donald Trump as different races prior to his election. The “What If He Were: Black-Asian-Hispanic-Middle Eastern-Indian” was originally commissioned by a prominent magazine, but the magazine decided not to publish the images. Despite this setback, Burson remained committed to her work. These images were her attempt to not only expose Trump as a racist, but to challenge public consciousness regarding racist beliefs in the US.

Even though the work depicting Trump could not be published in that magazine, Huffington Post eventually published it after it was shown at the Rose Gallery (Santa Monica, CA) in 2016.

Another work called “Trump/Putin” was selected for the cover of Time magazine in 2018. This work showcased a slow transformation of the faces of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin into one face. The image illustrated the sudden, unexpected liaison between thesse two leaders and the potential involvement by Russia in the 2016 election for the United States presidency.

Burson already knew the photo editor of Time magazine, Paul Moakley, who had selected one of her earlier works, “Androgyny” for Time’s book, “100 Photographs: The Most Influential Images of All Time”. Moakley was impressed by “Trump/Putin” and featured it on the cover of Time magazine. The image went viral immediately.

Nancy Burson's passion for addressing pressing political issues through art continues to this day, as evidenced by her recent work "The Face of Global Carbon Emissions". This piece depicts the top five heads of state whose countries are the biggest contributors to global warming. The composite image is weighted according to the approximate percentages of each country's carbon emissions. The featured leaders are Xi Jinping of China (contributing 28%), Joe Biden of the US (contributing 15%), Narendra Modi of India (contributing 7%), Vladimir Putin of Russia (contributing 5%), and Fumio Kishida of Japan (contributing 3%).

N.B.: “I prefer to make composites these days as political statements. “The Face of Global Carbon Emissions” grew out of my concern for our Mother Earth. We need to reduce our carbon emissions or risk extinction of humanity. I wanted to put a human face on the problem by combining the five world leaders who hold the power to change climate policies.”

Expressing social issues and bias

Nancy Burson has dedicated her career to exploring the complexities and mysteries of the human face and the societal issues it reflects. Faces have always been an important part of human communication and expression. Portraiture represents a person's likeness and has been used throughout history to depict individuals and their personalities, capturing their essence through subtle cues like facial expressions and body language. Nancy Burson does not use portraiture to represent personal expression. Rather, she highlights social, political, and cultural issues, focusing on larger societal biases and injustices.

The human face is a mysterious and changeable thing. Burson's art explores how it is influenced by social and scientific ideas and biases. Her work uncovers the fluidity of concepts such as beauty, sex, race, power, family, and even species. It challenges viewers to reevaluate their ways of seeing the world. She wants us to see the works and actively engage with them, instead of just decoratively viewing them.

Morphing Techniques and AI

Morphing techniques and many AI image generative programs blur the line between reality and illusion. AI can generate pictures and videos that appear almost real, and morphing techniques can allow for the seamless transition of one image into another. When these two technologies intersect, the possibilities for creating lifelike illusions are almost limitless.

One of the important AI examples of morphing techniques is the DeepFakes. It uses an AI algorithm to replace one person’s face with another realistic transformation. The technique raises deep concerns about the potential for creating fake news or propaganda.

Another example of the intersection of morphing techniques and AI is GAN (Generative Adversarial Networks). GAN is a type of deep learning model that can generate new realistic images by blending and morphing elements from other images. It is applied in various fields, like art, fashion, and design. In recent years, GANs have been used to create unique and visually striking art pieces that blend elements from different styles seamlessly. The resulting images are both surreal and captivating, blurring the line between reality and imagination.

Nancy Burson has been keeping a close eye on the advancements in technology, including the rise of artificial intelligence. While she acknowledges the potential benefits of this new tool, she also recognizes the potential for misuse and unintended consequences.

N.B.: “Each new technology brings its own potential misuses along with it. I consider AI to be a powerful new tool that I think is especially good at illustrating abstract concepts. Clearly some limitaitons have already been found, such as the software’s apparent racial bias that’s especially disturbing when used for law enforcement. I never imagined there would be a time that AI composited fake people would be used as spokespersons for websites. That’s terrifying to me.”

by Nancy Burson

Video work

Ed.: 6/10

On OpenSea: https://opensea.io/item/ethereum/0xcff69ef9ecd82d93e7a1be6a5aaac18ccf987536/1