Nicolas Schöffer and the Birth of Cybernetic Art

Nicolas Schöffer was a pioneering figure in cybernetic and kinetic art during the 1950s. Drawing inspiration from Norbert Wiener's cybernetic theories of control and feedback, Schöffer viewed art as more than mere static forms. To him, it was a dynamic, ever-evolving force. He conceptualized an artistic process rich with feedback loops, circular causality, and a fundamental emphasis on movement. In our article, we explore his masterpieces, inspirations, and major contributions.

Nicolas Schöffer, born on September 6, 1912, in the picturesque town of Kalocsa, Hungary, was exposed to diverse influences from a young age. His mother, a violinist, encouraged his artistic interests, while his lawyer father gave him practical values. Despite his growing artistic tendencies, his father's doubts about the sustainability of an art career prompted Schöffer to pursue law in Budapest. He believed that his legal studies sharpened his complex and constructive thinking, qualities he considered essential for the intricate artistry he would later undertake.

After completing his law studies, Schöffer's passion led him to the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest. By 1936, drawn by the allure of a broader artistic landscape, he relocated to Paris. Looking at his mature works, it's surprising to note his initial attempts at expressionist and surrealist paintings. In Paris, the International Exposition of Art and Technology had a profound influence on him, igniting a passion for intertwining scientific research with art. This experience reshaped his artistic style, setting him on a path of innovation that would define his entire career.

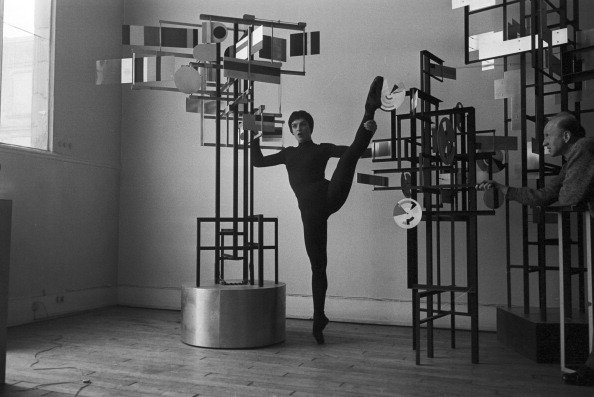

‘CYSP1’ with a ballet dancer © cyberneticzoo.com

Around 1947, Schöffer's artistry began to flourish. He started producing constructivist spatial sculptures and reliefs, grappling with the intricate relationship between space and motion. He conceptualized abstract forms in three-dimensional space, and these ideas influenced his creations on two-dimensional canvases. For Schöffer, the canvas evolved not just as a backdrop, but as a spatial dimension. His progression led him to create relief images, subtle extensions from their foundational surface. The influence of Mondrian's Neoplasticism began to permeate his works, characterized by stark contrasts and a limited yet impactful color palette.

It was during this period when Schöffer encountered Norbert Wiener's work on cybernetic principles, which shifted his artistic concept. Cybernetics was introduced by Norbert Wiener in 1948 through his book, ‘Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine.’ This work revolutionized the understanding of systems, control, and communication in animals, machines, and organizations. Nicolas Schöffer's sculptures became living embodiments of Wiener's concepts. Thanks to advancements in science and technology, Schöffer could realize all of his artistic visions.

He created moving, illuminating sculptures and installations that emitted sounds in collaboration with engineers, architects, composers, and dancers. For Schöffer, the viewer's experience was at the heart of his artworks. His unique approach seamlessly melded art, technology, and science, often demanding collaborative efforts. He championed interactive art, allowing viewers to alter and thus co-create the artwork.

Schöffer's artistic career can be divided into three major periods: Spatiodynamism, Luminodynamism and Chronodynamism

Spatiodynamism (1950-1957)

After initially focusing on sculptures designed to be viewed from a primary angle, Schöffer began creating works where every perspective held value. These sculptures had asymmetrical steel frames with colored plates and discs, later substituted with aluminum and steel sheets. These reflective materials enhanced the dynamic quality of the sculptures by mirroring their surroundings, giving them a pronounced presence. While most of these sculptures remained stationary, their dynamic nature became evident as viewers moved around them. However, one particular work would break this stationary mold.

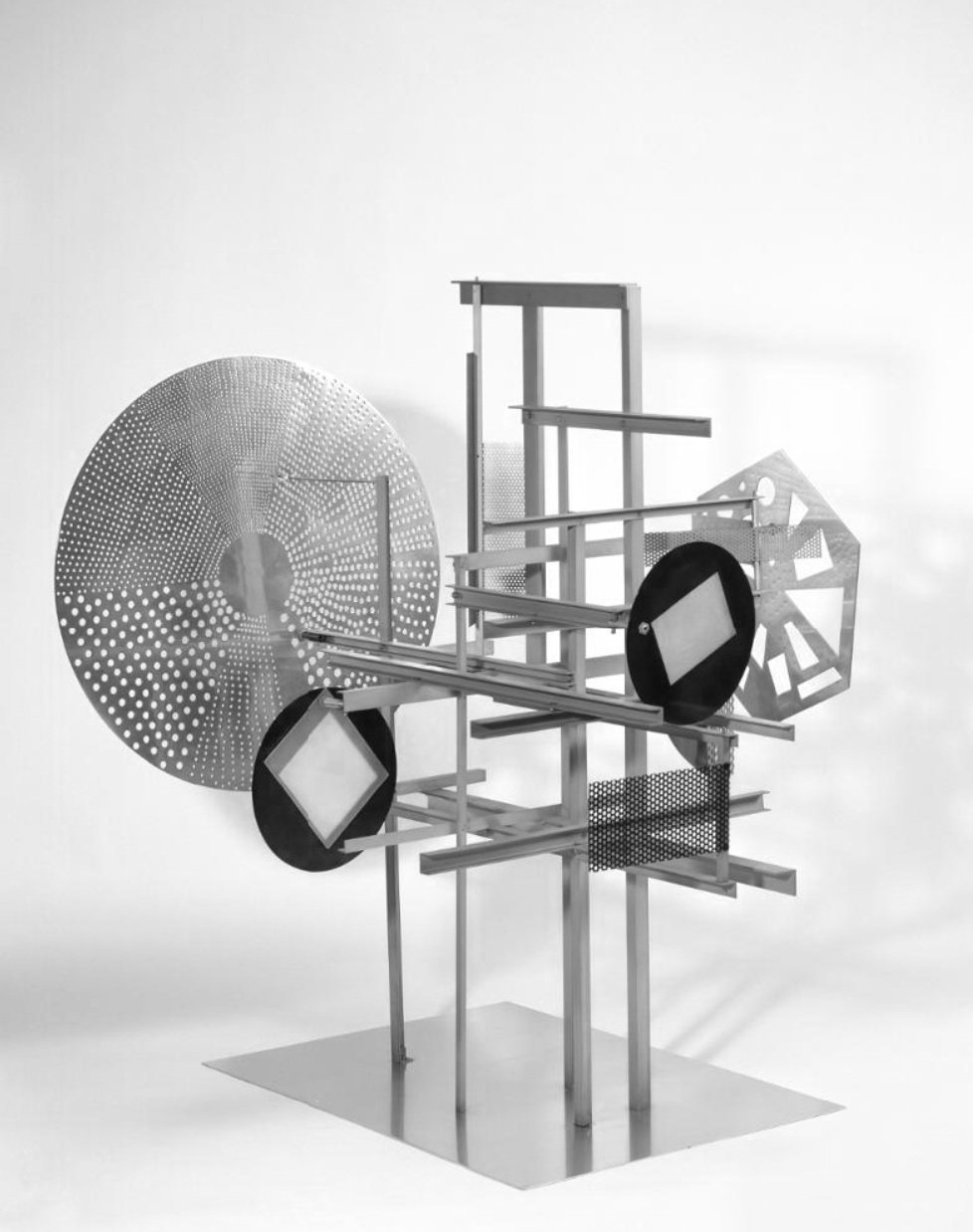

‘LUX 1’, 1959 © Adagp, Paris

In 1956, he introduced ‘CYSP1’, hailed as the first cybernetic sculpture in art history. Unlike his previous stationary pieces, this work was in constant motion. The sculpture's name originates from its cybernetic and spatiodynamic attributes. It showcased impressive mobility, moving freely in all directions and displaying axial and eccentric rotations that animated its 16 shifting, colorful plates. Developed in collaboration with the Philips Company, it was mounted on rollers, with each plate powered by individual motors. Built-in phototubes and a microphone detected changes in color, light, and sound, prompting the sculpture to react. CYSP1 made its debut at Paris's Sarah Bernhardt Theater during a poetry night in 1956. Later that year, at the Avant-garde Art Festival, Maurice Béjart's ballet dancers interacted with CYSP1 at Le Corbusier's Cité Radieuse in Marseille. The sculpture responded to their movements, establishing a unique partnership between humans and machines.

Luminodynamism (1957-1959)

After positioning his sculptures in space, Schöffer became fascinated with the interplay of light upon them. The kinetic sculptures after 1957 showcased polished plates that reflected light, creating a dynamic dance of illumination. This play of light and reflections not only deconstructed the artwork visually but also merged it with its surroundings. The distinction between the piece, its environment, and the observer began to blur. On April 14, 1956, Schöffer introduced this groundbreaking concept to the patent office, and by August 25, 1958, it was officially patented. From this idea, Schöffer developed the theory of Luminodynamism.

An important series during this time was the ‘LUX’ series. While its foundational idea drew parallels with Moholy-Nagy's light-space-modulator, the actual design of Schöffer's sculptures was distinct. These pieces, framed by horizontal and vertical square profiles, also featured attached discs and plates. Hidden motors caused the sculpture and the metal plates to rotate rapidly. Illuminated from various angles, the aluminum reflects light in all directions, creating shadow plays. These were amplified by perforated plates filtering the light while transparent screens captured luminous images within the sculpture itself, making it akin to a shadow theater. The resulting shadows on adjacent walls became an integral component of the artwork itself.

‘Tour Cybernétique’ in Liège, Belgium, 1961 © elephant.art

Chronodynamism (1959-)

Chronodynamism evolved from the earlier concept of Luminodynamism but added the dimension of time. It not only dealt with how light played on objects but also with the dynamic, changing nature of the interaction over time, often using cybernetics and automation. It's a more holistic approach, factoring in the temporal evolution of a work's relationship with its environment.

During this period, Schöffer created cybernetic light towers, the ‘Chronos’ series, which stand as a testament to cybernetics theory. The most accomplished and tallest cybernetic light tower was the "Tour Lumière Cybernetique" a proposal for a 324-meter interactive building in Paris. The design included movable metal plates controlled by a computer, allowing the structure to dynamically respond to light. This grand vision attracted collaboration from ten major French corporations, who developed detailed plans under Schöffer's guidance. The tower’s design is intended to incorporate a complex arrangement of mirrors, rotatable axes powered by electric motors, electronic flashes, headlights, and weather instruments. A spectacular addition of 15 large lights at its top was meant to give the tower an optical height of an astounding two kilometers. It was envisioned as a functional building with amenities like restaurants, TV stations, concert halls, post offices, and shops, serving diverse purposes—from an art space to a weather tower.

The tower project received support from prominent figures such as Charles de Gaulle, Georges Pompidou, André Malraux, and leaders from the Philips company. However, fate intervened; the death of the supporter Pompidou and financial disruptions caused by two oil crises meant the tower remained unrealized. Though the original tower was never built, a smaller version called the ‘Tour Cybernétique’ stands in Liège, Belgium. Subsequent versions appeared in cities including Washington, Montevideo, San Francisco, Bonn, Munich, Paris, Pont-d'Ain, and Lyon. Chronos 8 resides in Schöffer’s hometown in Kalocsa, near the house where he was born. His house now hosts a museum that showcases his artistic practice and primary artworks.

Cybernetic city (1965-)

One of Nicolas Schöffer's most ambitious endeavors was his vision for the ‘Cybernetic City’. In 1965, he was among the founders of the International Group for Prospective Architecture. Their manifesto highlighted the inadequacy of traditional housing and urban structures in addressing modern needs, underlining the importance of forward-thinking urban designs. This mindset propelled Schöffer to create a futuristic city. The ‘Cybernetic City’ stands as a testament to functional design, composed of three interconnected sections overseen by a cybernetic control center. It features designated zones for work and contemplation, while other areas are earmarked for residence and leisure. To him, the city was an extension of sculpture. He envisioned a vertical workspace populated with skyscrapers housing a cybernetic hub, administrative units, universities, and offices. Conversely, living spaces sprawled horizontally. He believed advancements in automation and cybernetics would grant people more leisure time, and hence, catering to recreational needs was important in his city design.

While Schöffer's grand vision was not fully realized, its essence persists, shaping modern perspectives on urban design and art. Tragically, Schöffer's creative journey was cut short by a severe stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body, confining him to a wheelchair. This condition prevented the birth of new large-scale artistic endeavors.

Schöffer's works are showcased in prestigious institutions such as the Centre Pompidou, The Museum of Modern Art, and the Stedelijk Museum. His contributions to cybernetics continue to reflect a harmonious interplay between human creativity and machine intelligence, inspiring new generations of artists.