Remembering Desmond Paul Henry: Pioneer of Machine-Generated Art

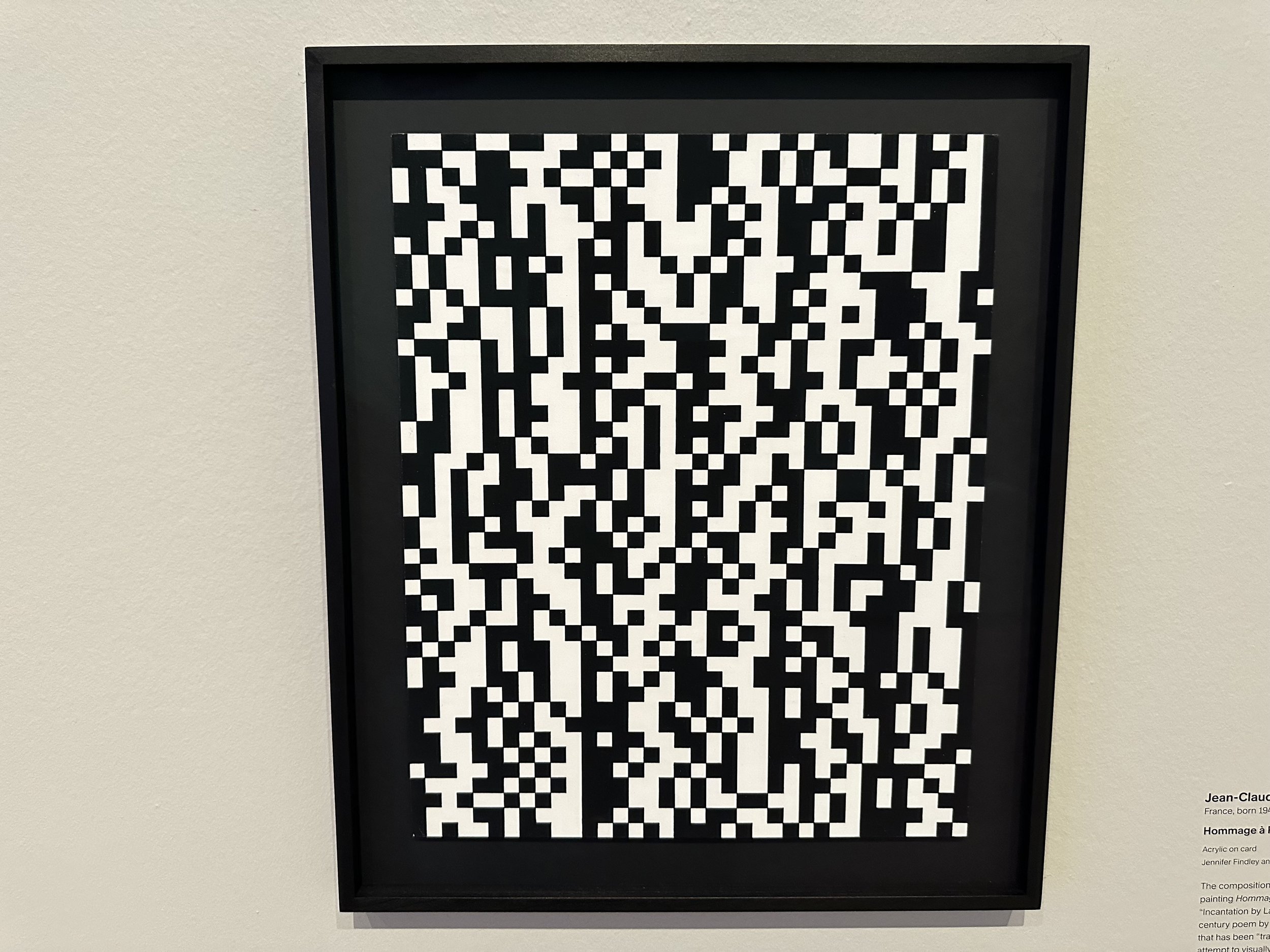

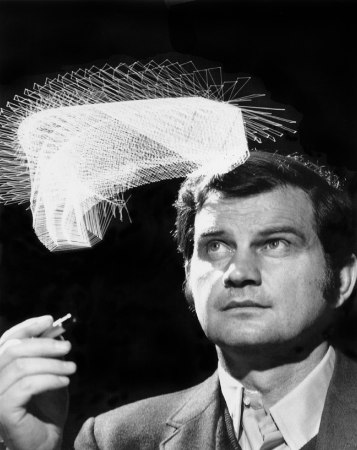

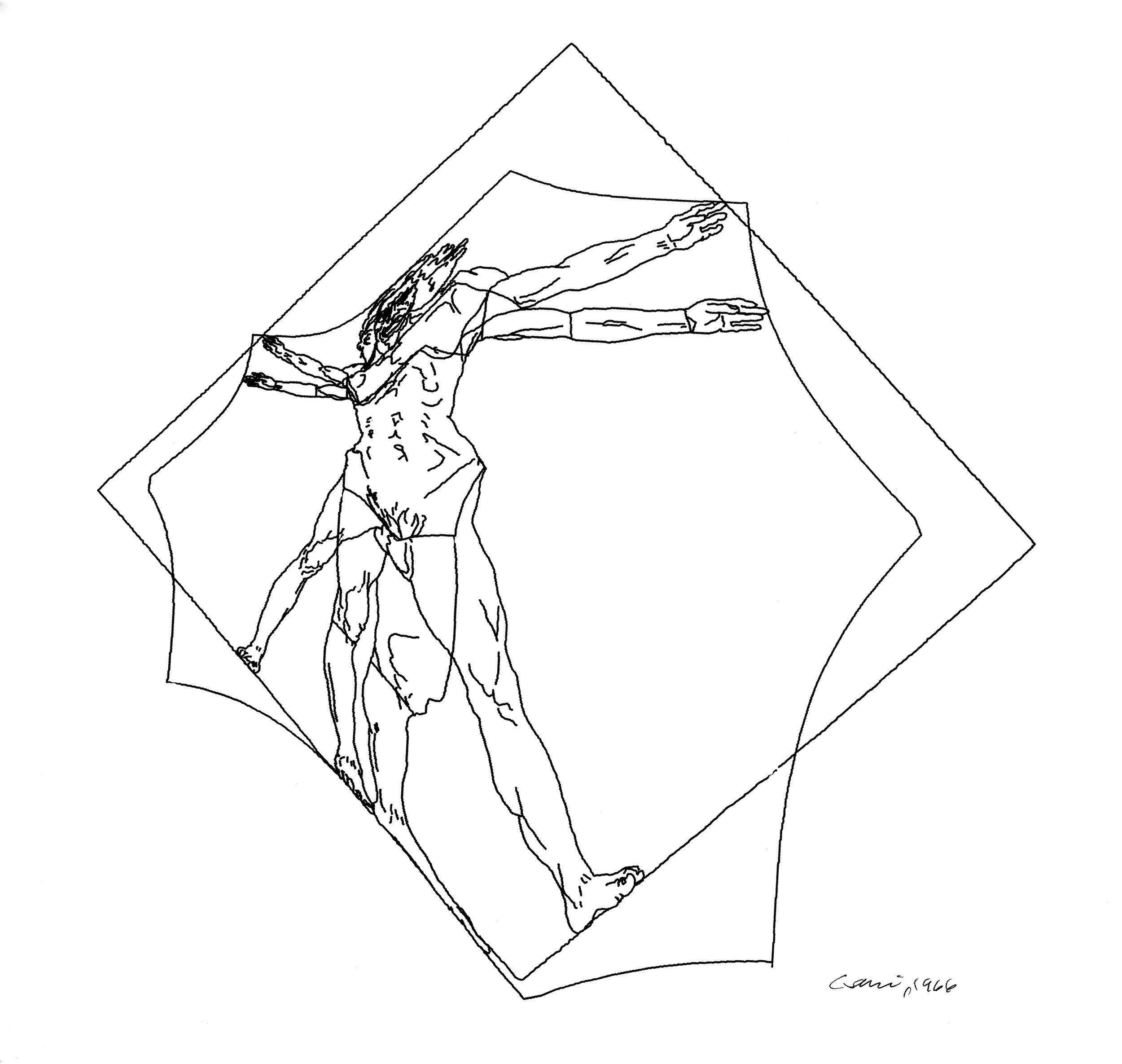

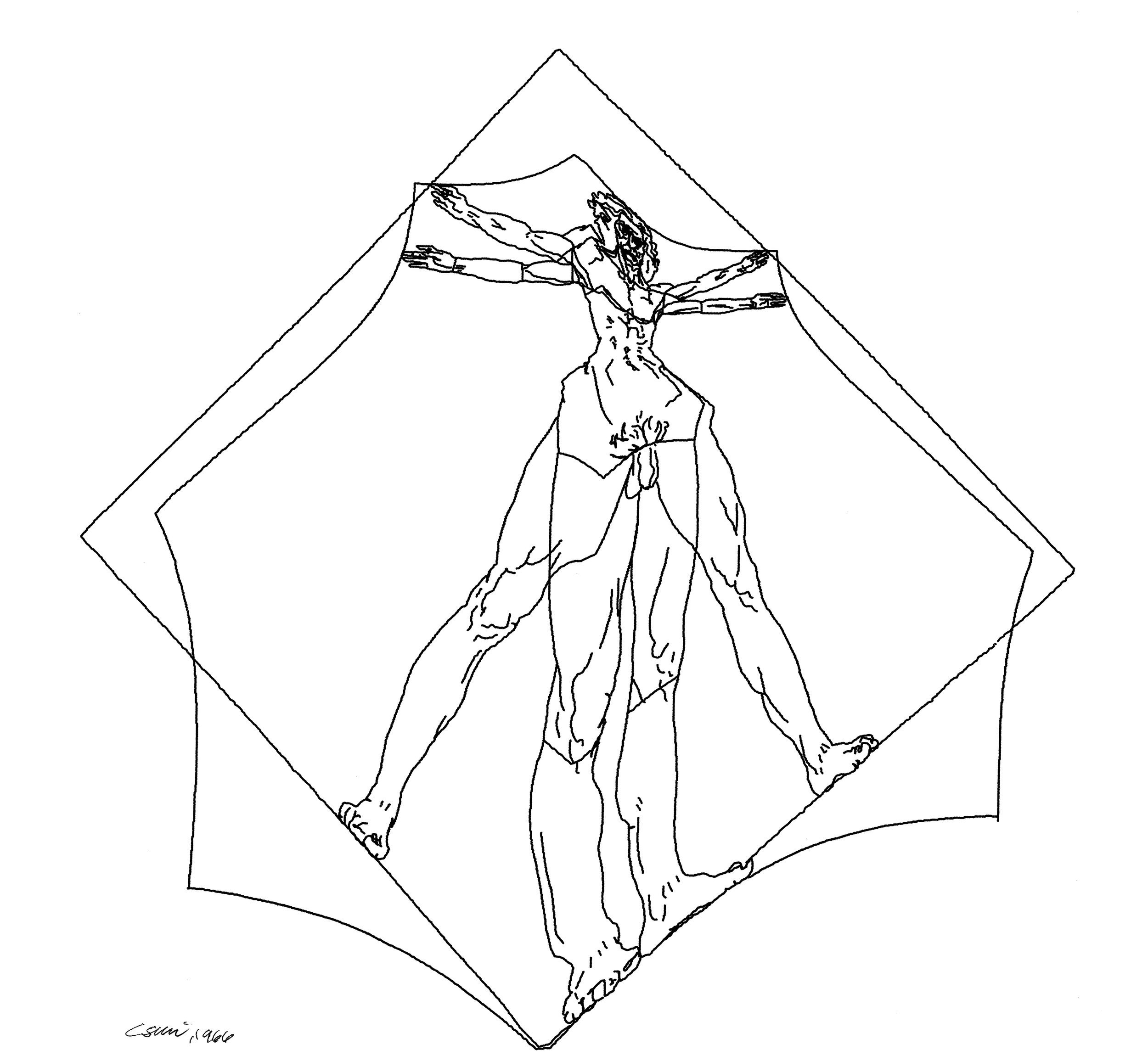

Today, we commemorate the birthday of the artistic visionary, Desmond Paul Henry (1921-2004), whose pioneering approach to art continues to influence and inspire. An esteemed philosopher and Manchester University lecturer, Henry was at the forefront of the global computer art movement of the 1960s. It was in our historical exhibition, "Automat und Mensch," where we had the honor of showcasing Henry's beautiful machine-generated pieces.

Today, we commemorate the birthday of the artistic visionary, Desmond Paul Henry (1921-2004), whose pioneering approach to art continues to influence and inspire. An esteemed philosopher and Manchester University lecturer, Henry was at the forefront of the global computer art movement of the 1960s. It was in our historical exhibition, "Automat und Mensch" where we had the honor of showcasing Henry's beautiful machine-generated pieces.

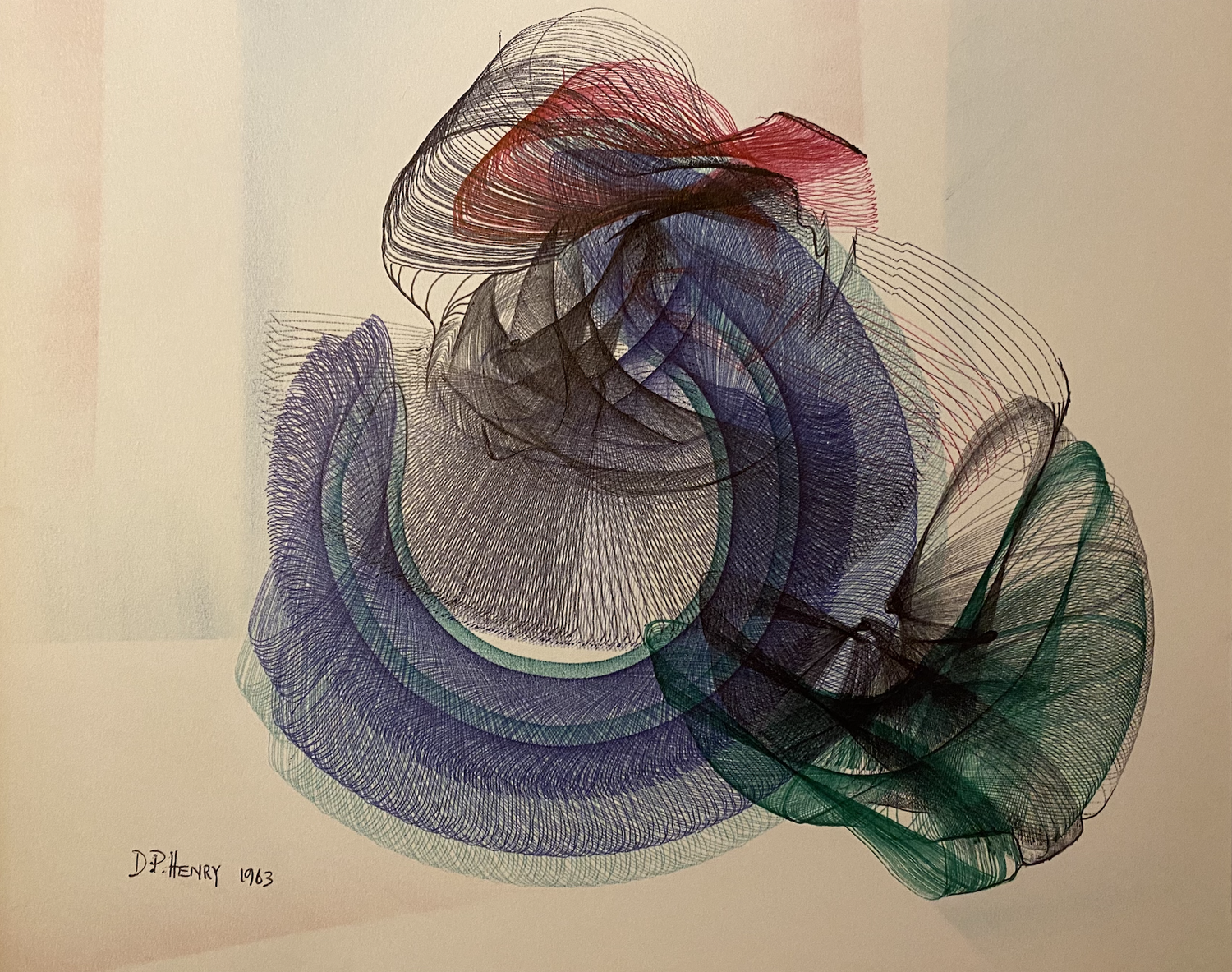

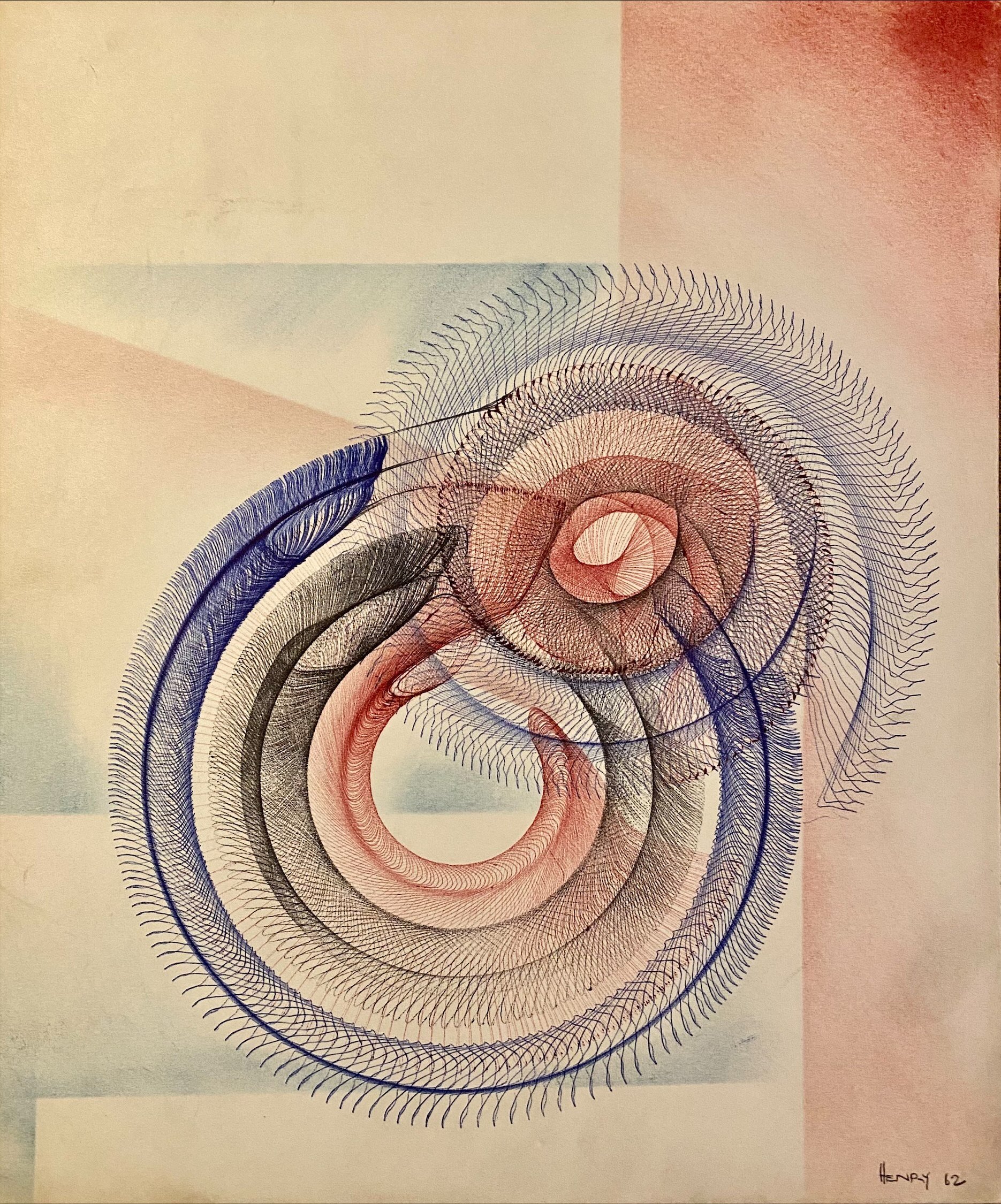

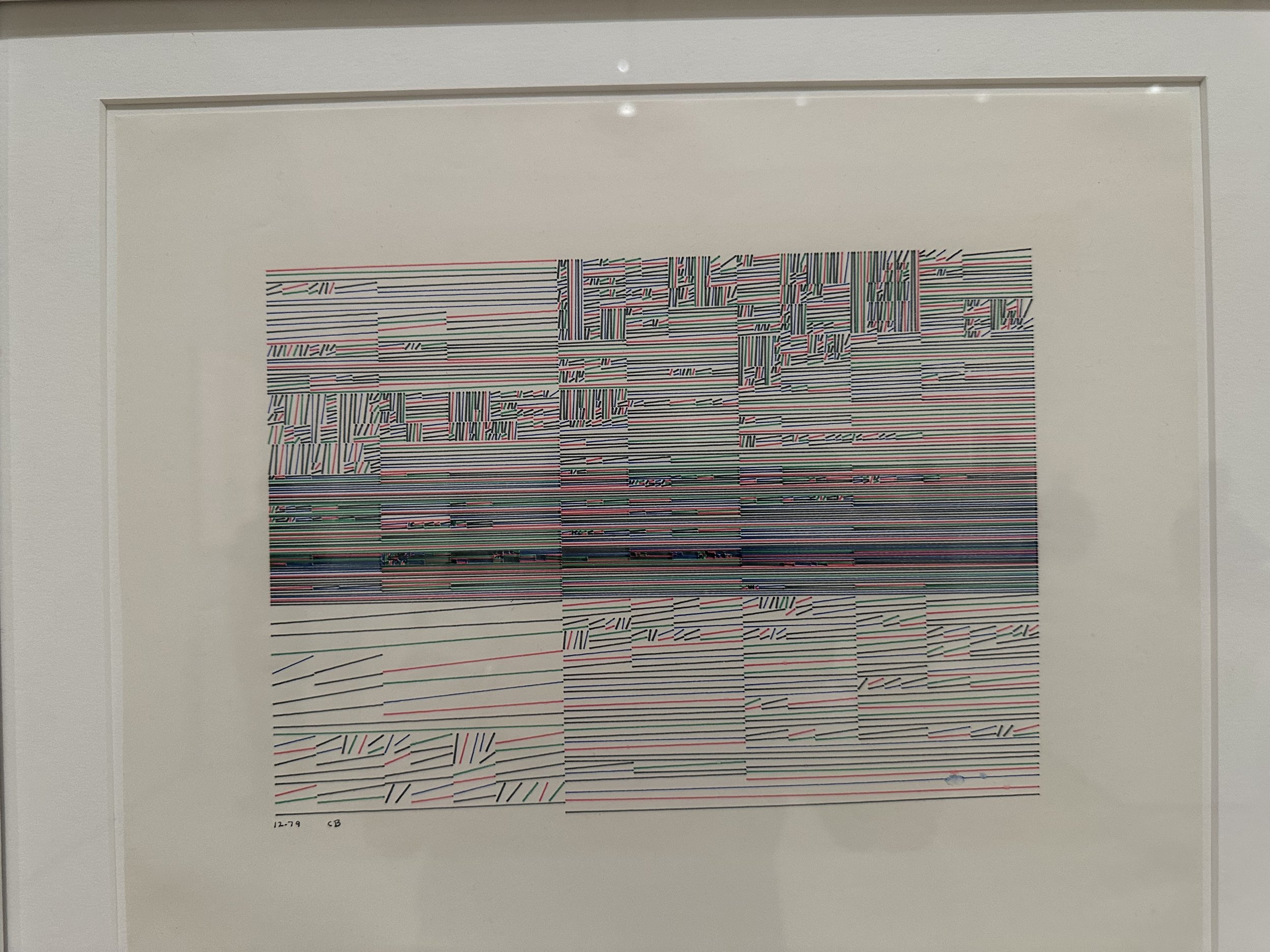

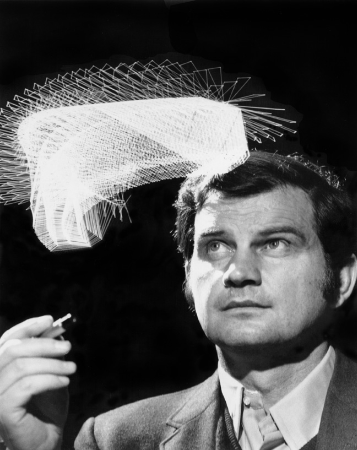

Born on July 5th, 1921, Desmond Paul Henry was a visionary exponent of the synergy between art and technology. He pioneered the concept of using computers for interactive graphic manipulation. His analog computer-derived drawing machines from the 1960s serve as a crucial bridge between the Mechanical Age and the Digital Age.

In 1961, thanks to celebrated artist L.S. Lowry and A. Frape, Henry's career reached new heights when he won first prize in a "London Opportunity" art competition. Lowry, recognizing Henry’s potential, insisted on showcasing his machine drawings at Henry's London solo exhibition, titled “Ideographs”, at the Reid Gallery. Henry's groundbreaking work in machine-generated art caught the attention of the media, landing him a spot on the BBC's North at Six series and drawing interest from the American magazine, Life.

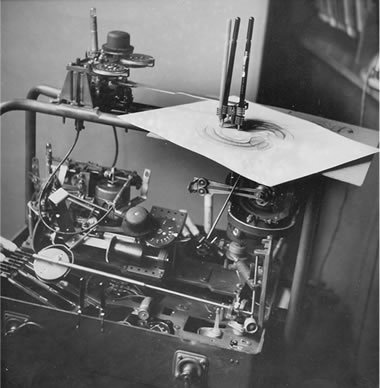

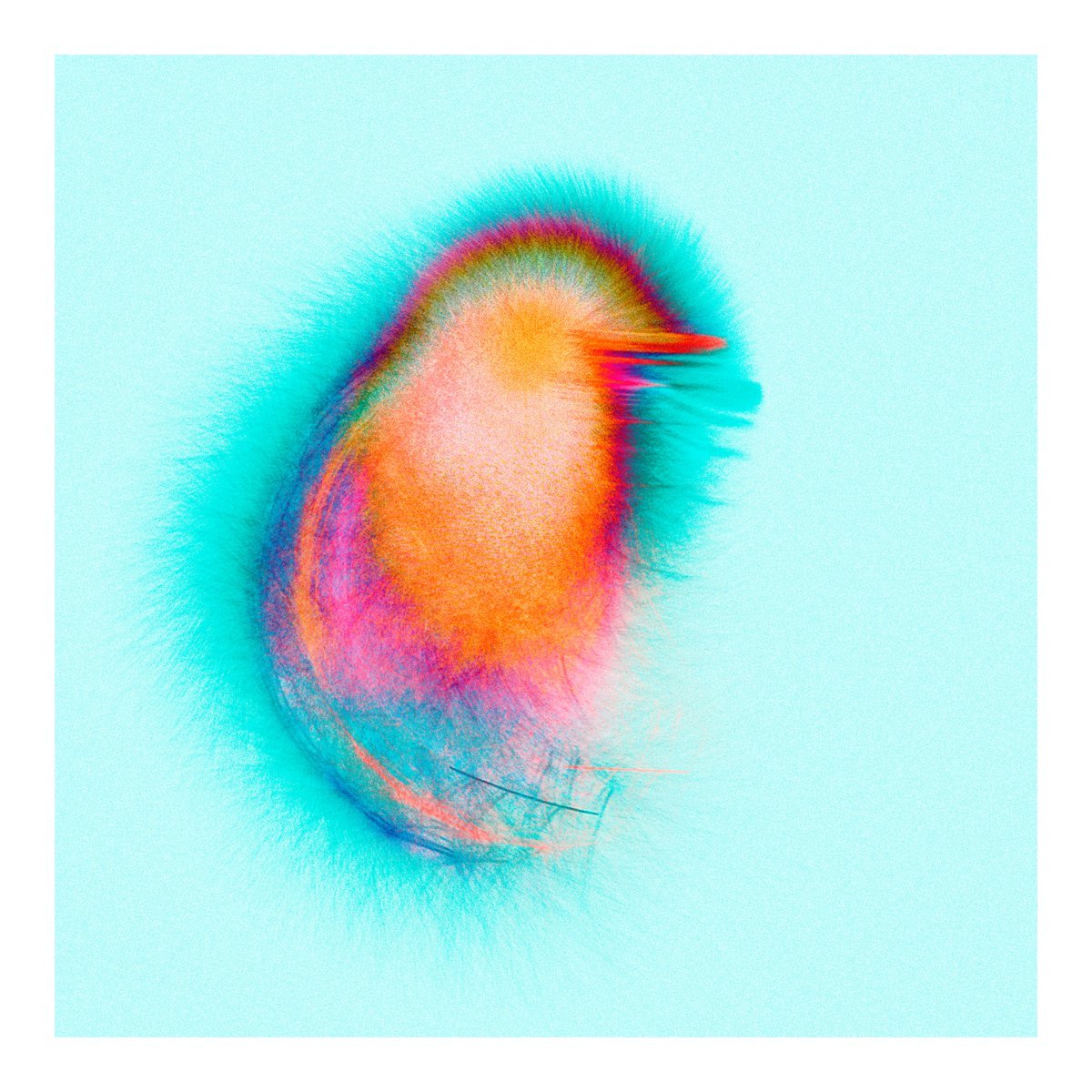

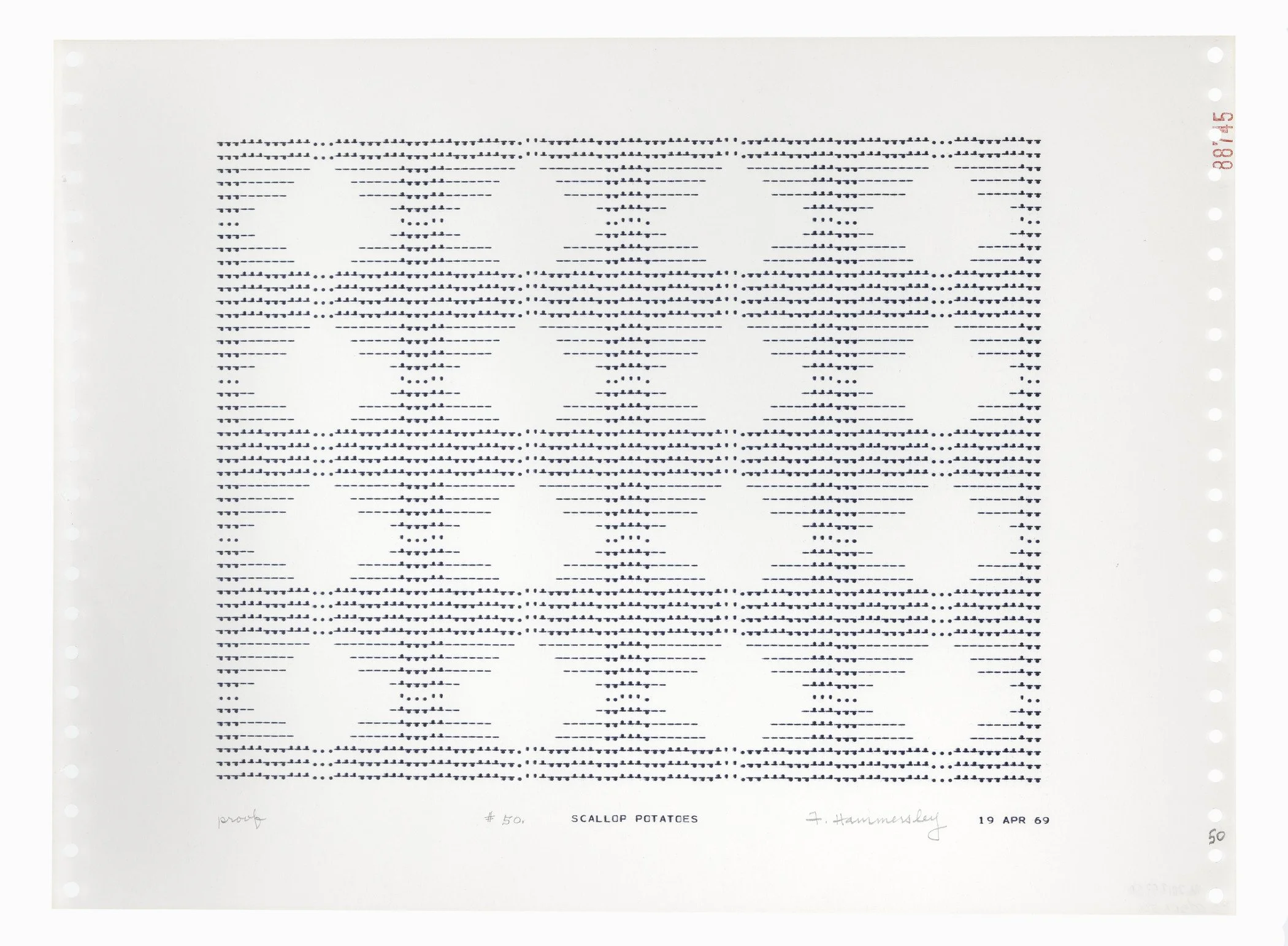

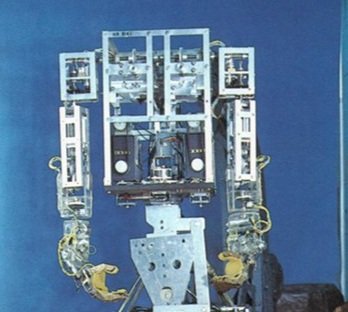

One of Henry’s Drawing Machines Copyright © Desmond Paul Henry 2023

Henry's pieces were featured in various exhibitions during this period, including "Cybernetic Serendipity" held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. This exhibition, featuring his interactive Drawing Machine 2, toured the United States, amplifying his international recognition.

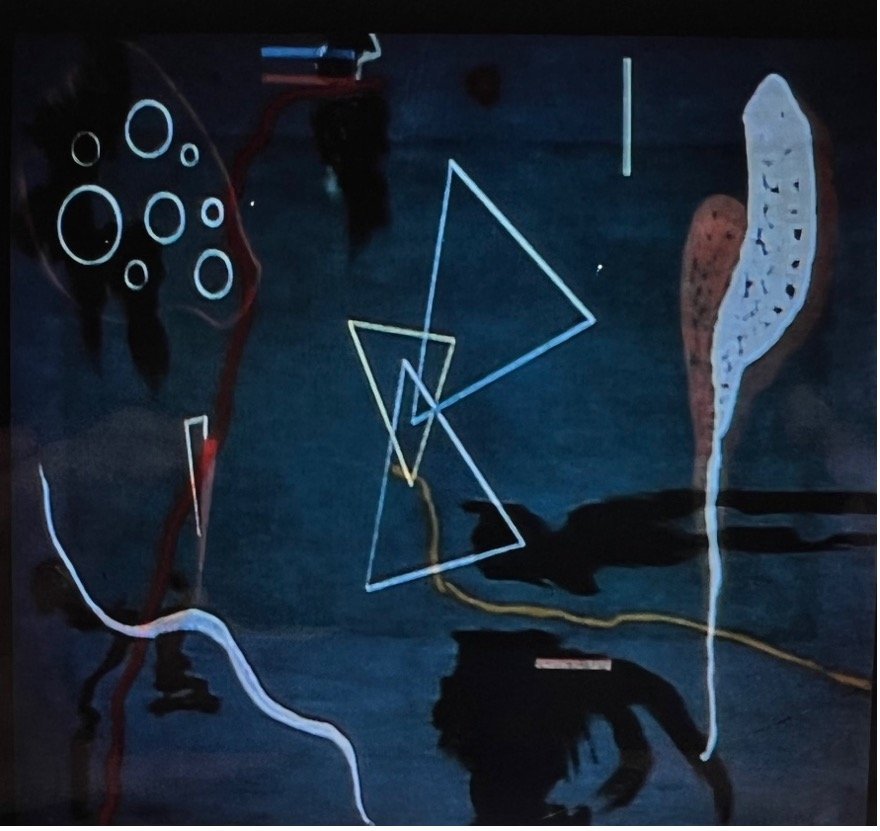

Henry constructed three electro-mechanical drawing machines from modified bombsight analogue computers (a technology primarily used in World War II bombers to calculate the precise release of bombs onto their targets). His drawing machines were not merely functional; they were intricately designed systems that combined gears, belts, cams, and differentials. Each machine took up to six weeks to construct. The resulting drawings, each creating a symphony of lines and curves, could take from two hours to two days to complete. Powering these machines required an external electric source, driving one or two servo motors that coordinated the motions of the suspended drawing implements.

Henry's electromechanical drawing machines embraced the unpredictable beauty born from the "mechanics of chance" like the works of artist Jean Tinguely. However, his creations also allowed for interactivity, allowing for personal and artistic input during the drawing process.

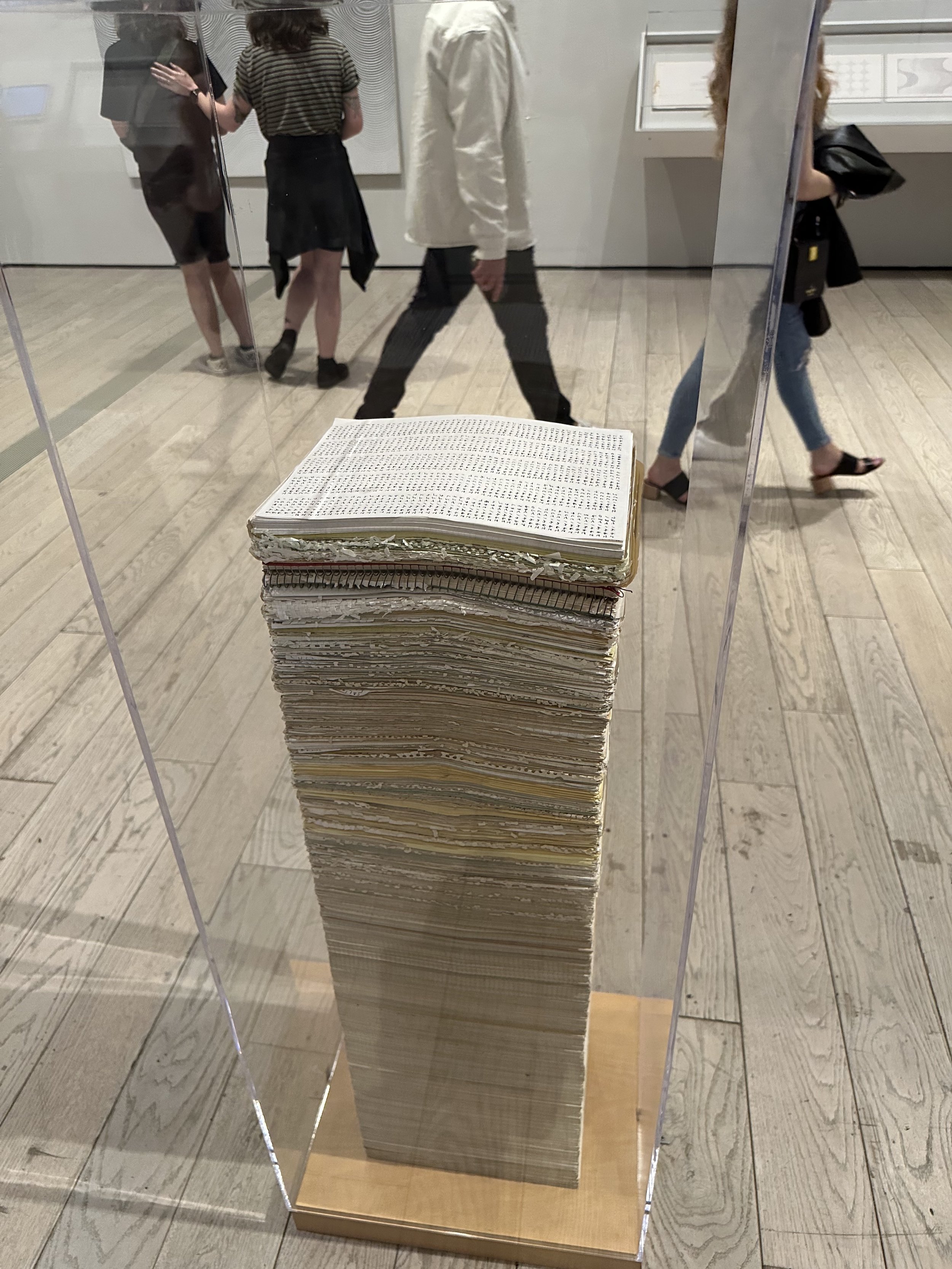

During this period, he created around 800 machine-drawings, each an infinitely varied combination of repetitive single lines forming abstract curves. Some of these works were exhibited in 2019 at the “Automat und Mensch – A History of AI and Generative Art” exhibition at Kate Vass Galerie, along with other historically significant generative artworks.

Artworks

Happy Birthday to Kjetil Golid!

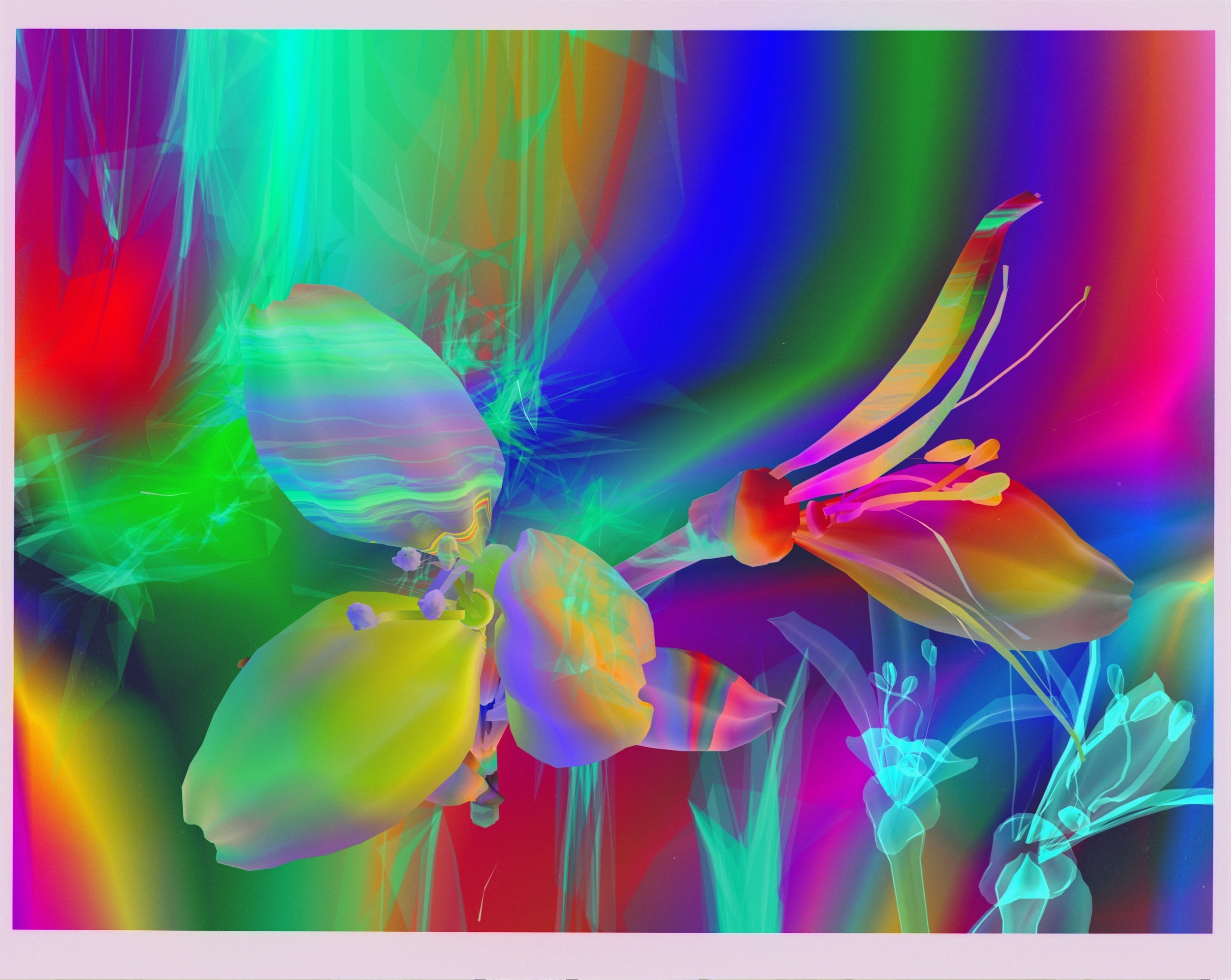

Celebrating the birthday of artist Kjetil Golid, we take a closer look at his remarkable career in generative art. Hailing from Norway, Kjetil explores algorithms and data structures through captivating visualizations. His projects fuse aesthetic visuals with original algorithms, resulting in mesmerizing and unpredictable outcomes. Kjetil advocates for creative expression through programming, openly sharing his code and even developing user-friendly tools for non-coders to create interactive visuals.

Celebrating the birthday of artist Kjetil Golid, we take a closer look at his remarkable career in generative art. Hailing from Norway, Kjetil explores algorithms and data structures through captivating visualizations. His projects fuse aesthetic visuals with original algorithms, resulting in mesmerizing and unpredictable outcomes. Kjetil advocates for creative expression through programming, openly sharing his code and even developing user-friendly tools for non-coders to create interactive visuals.

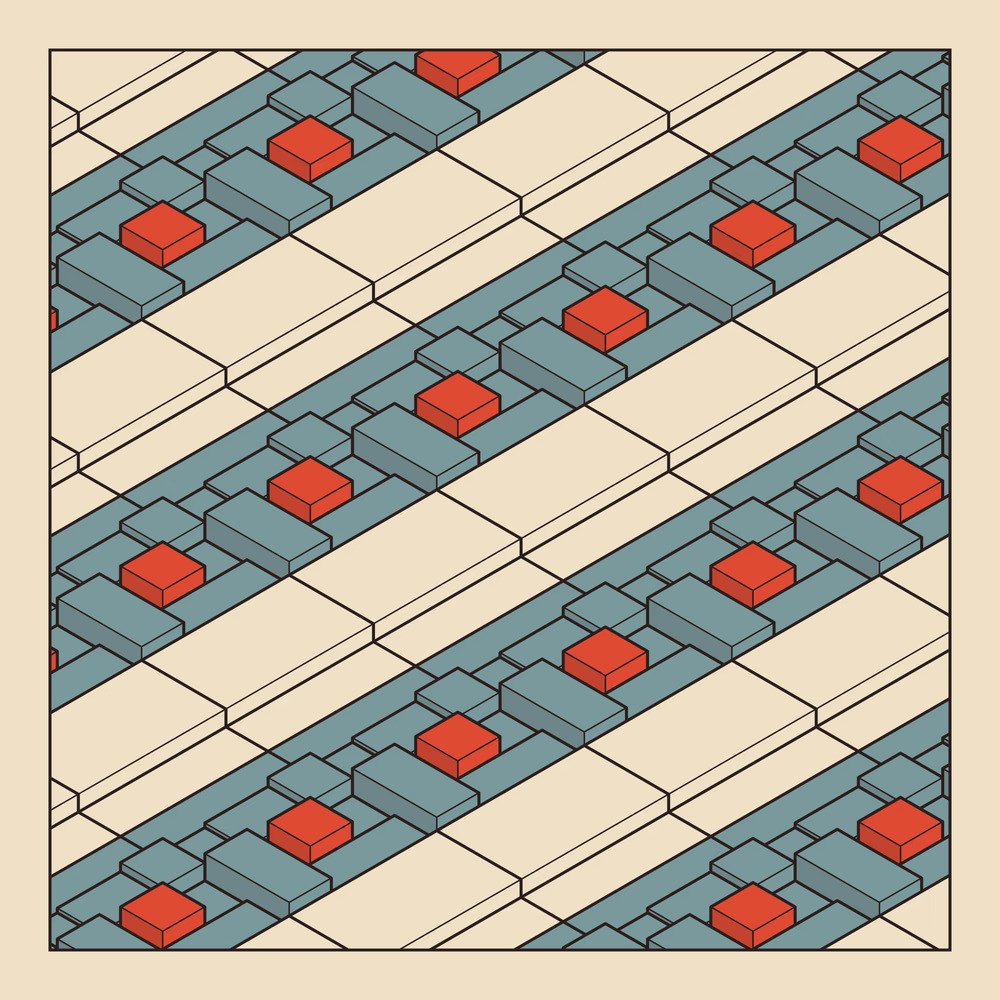

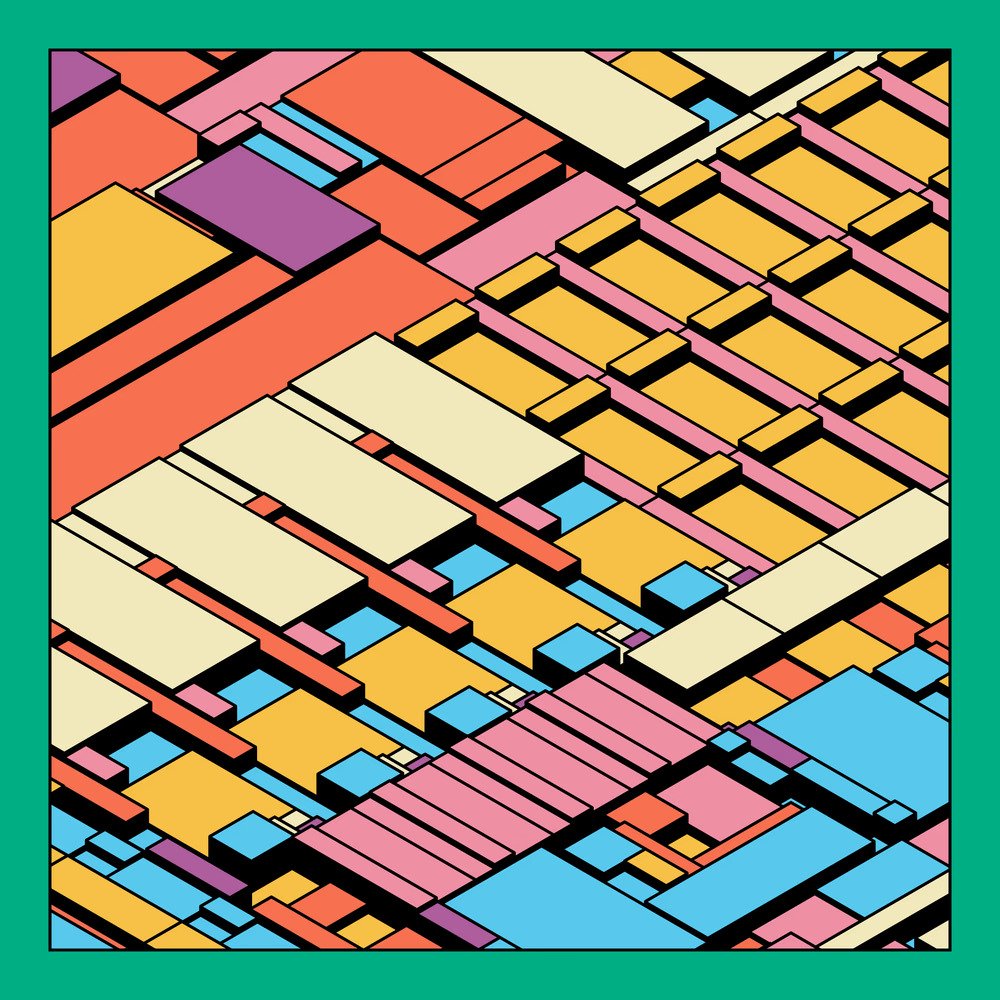

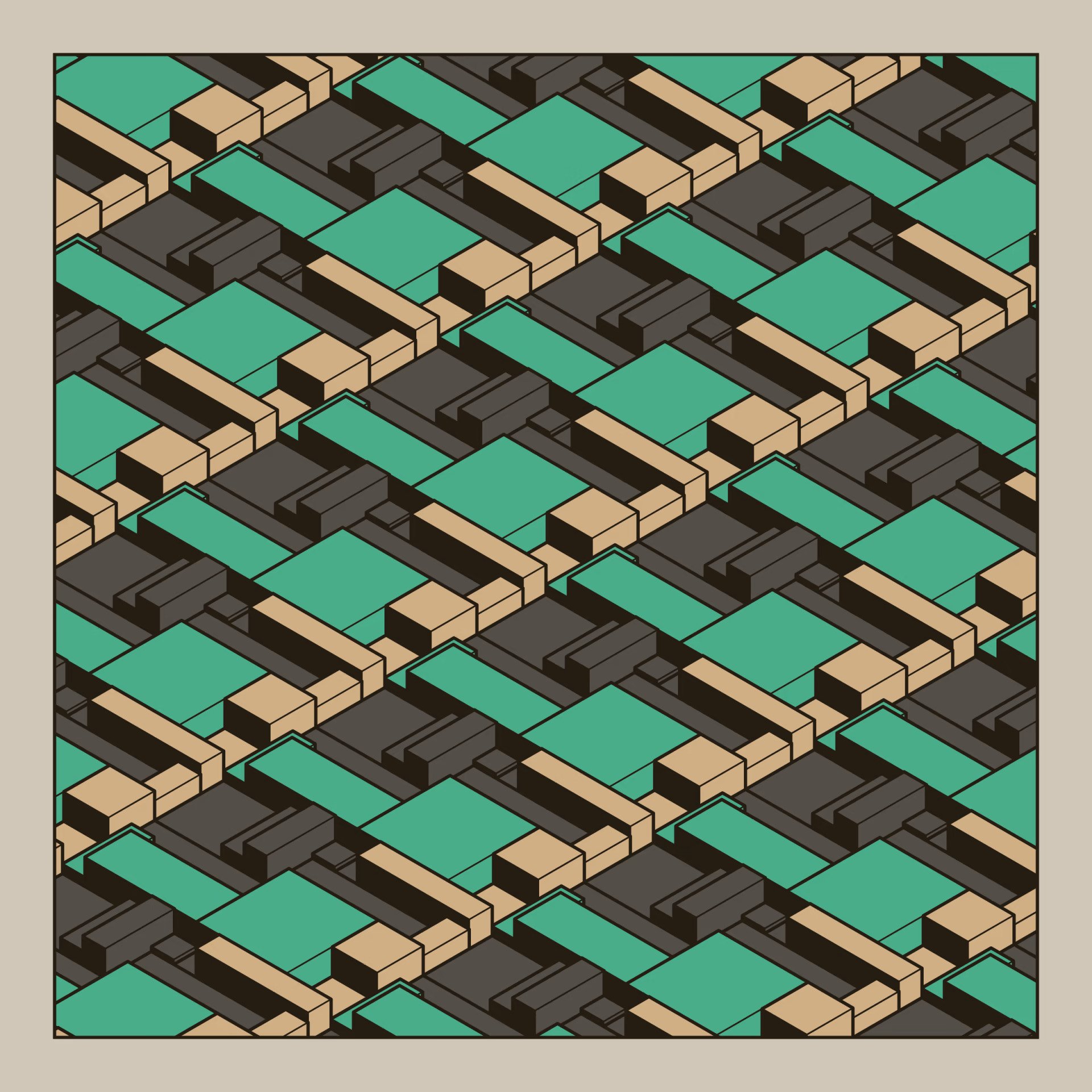

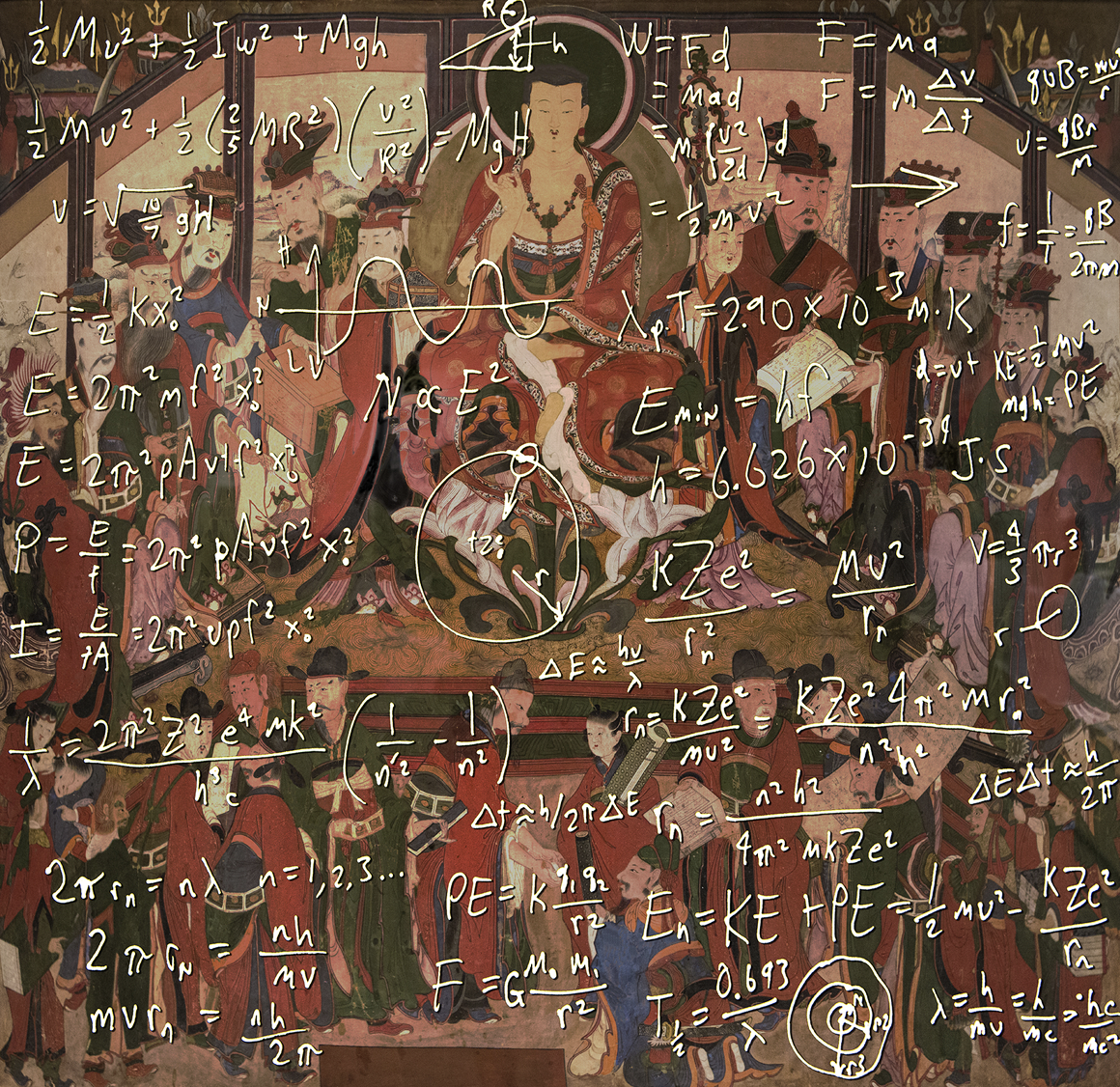

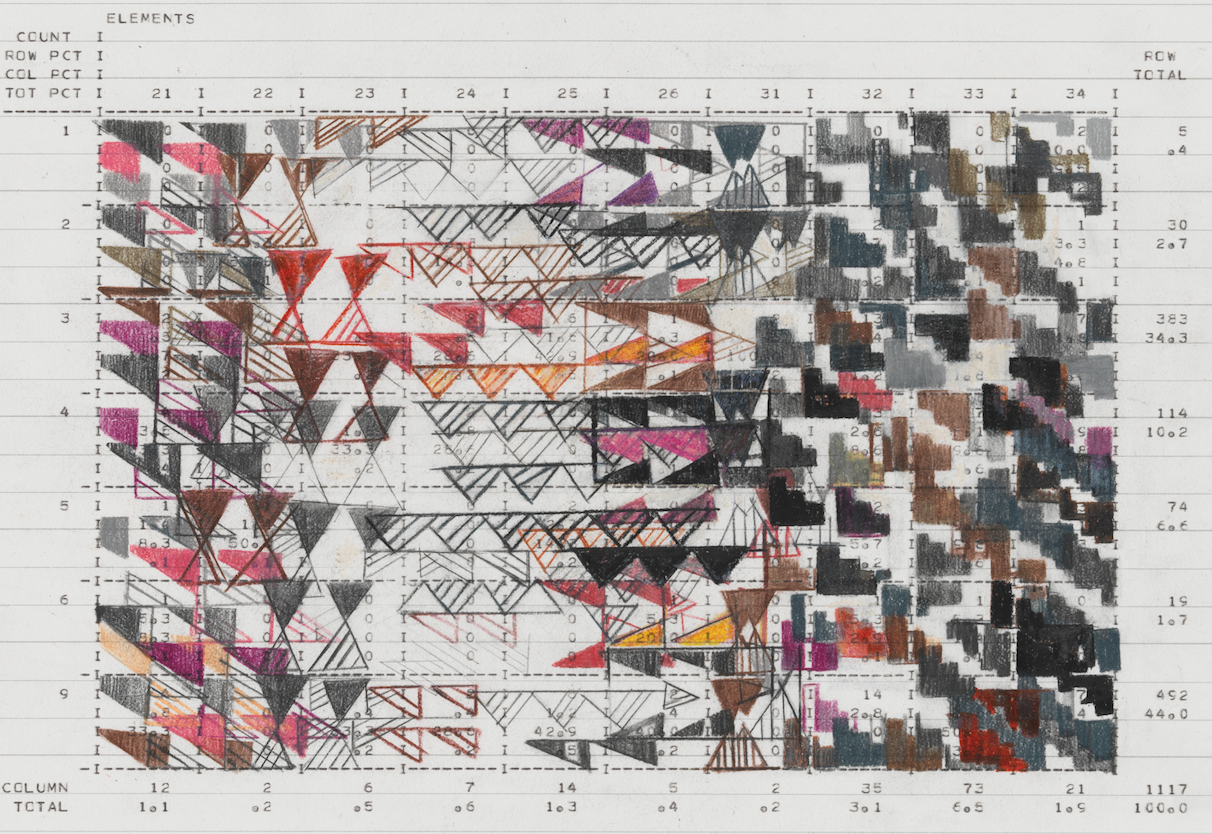

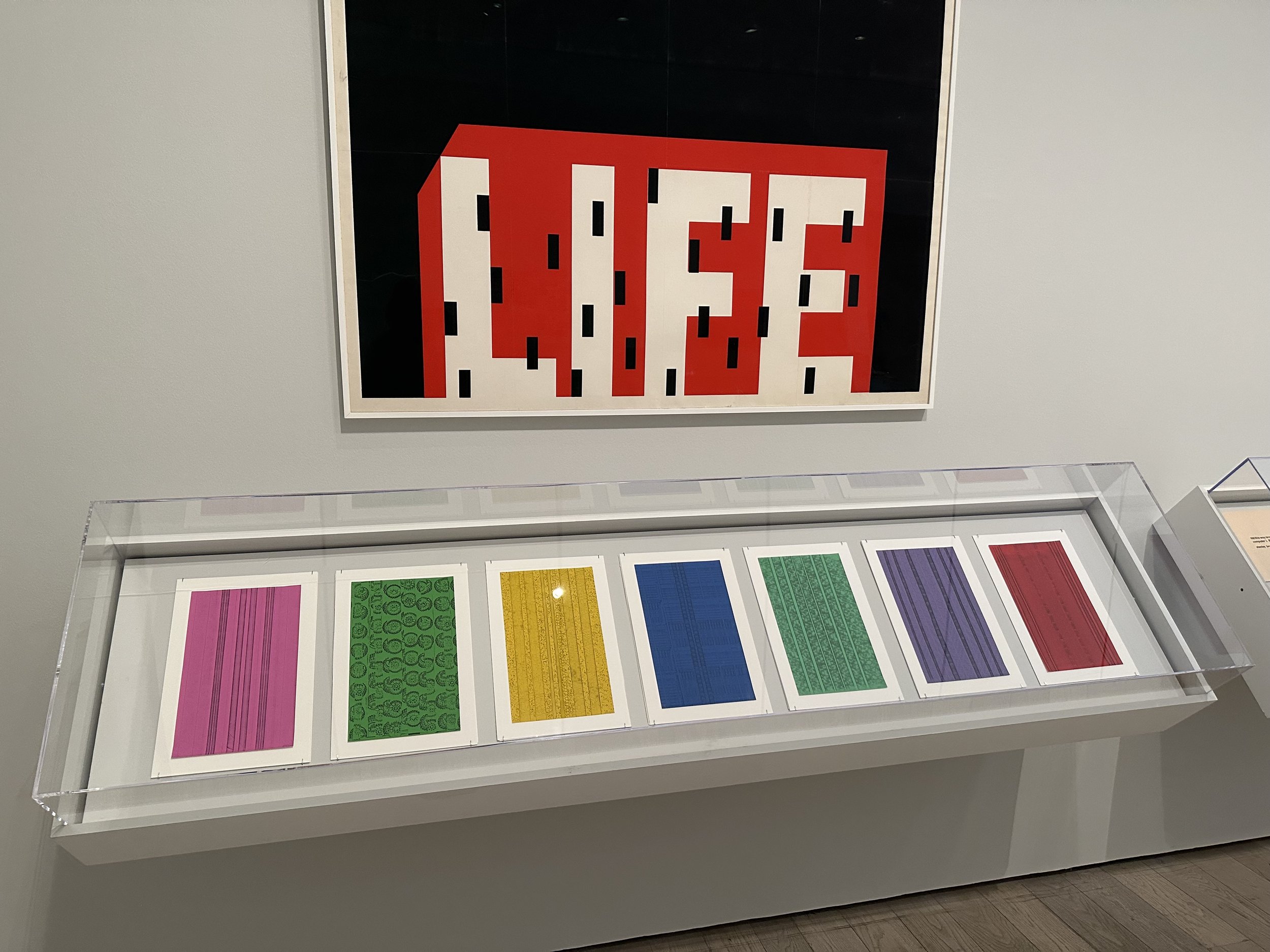

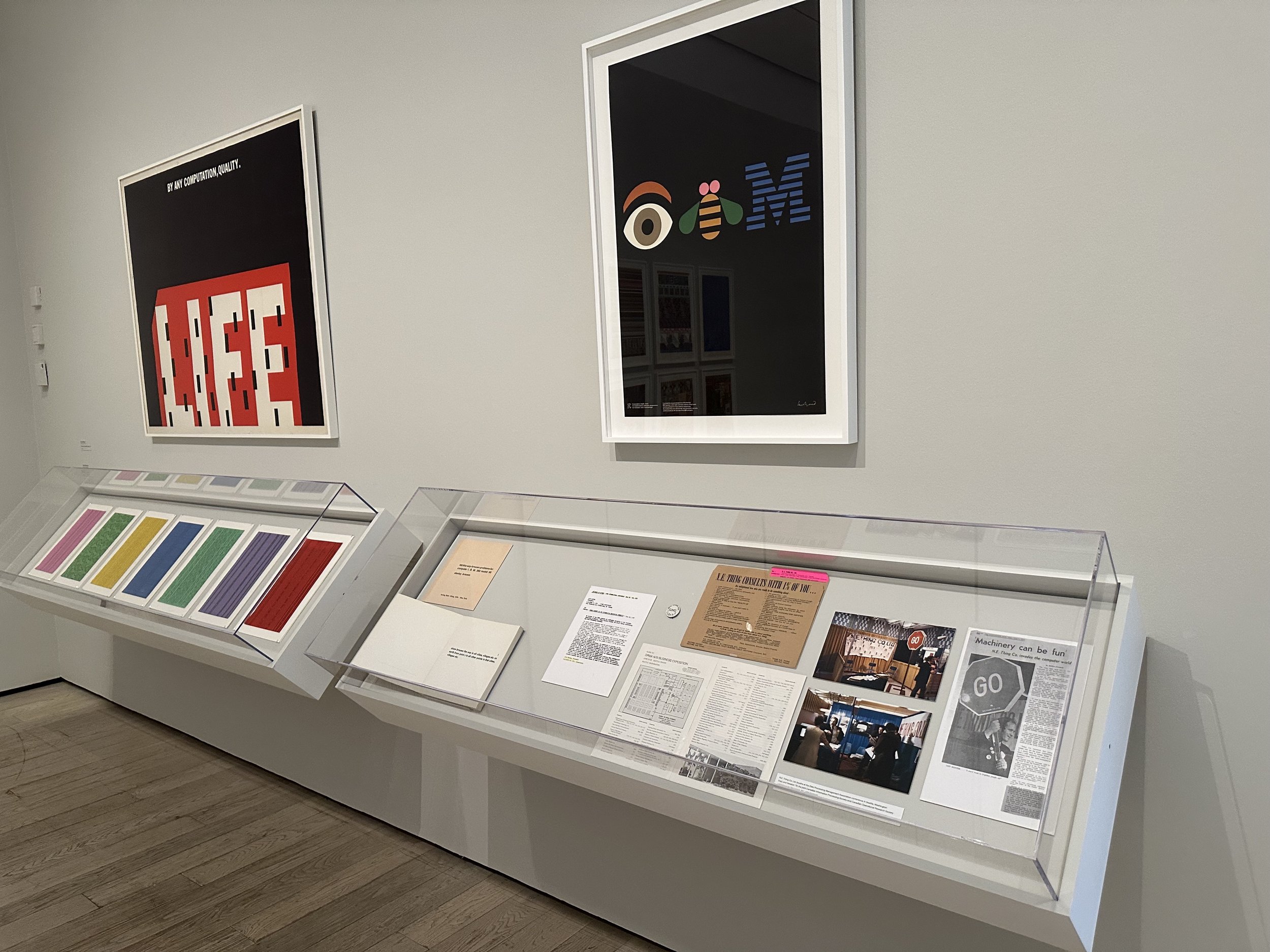

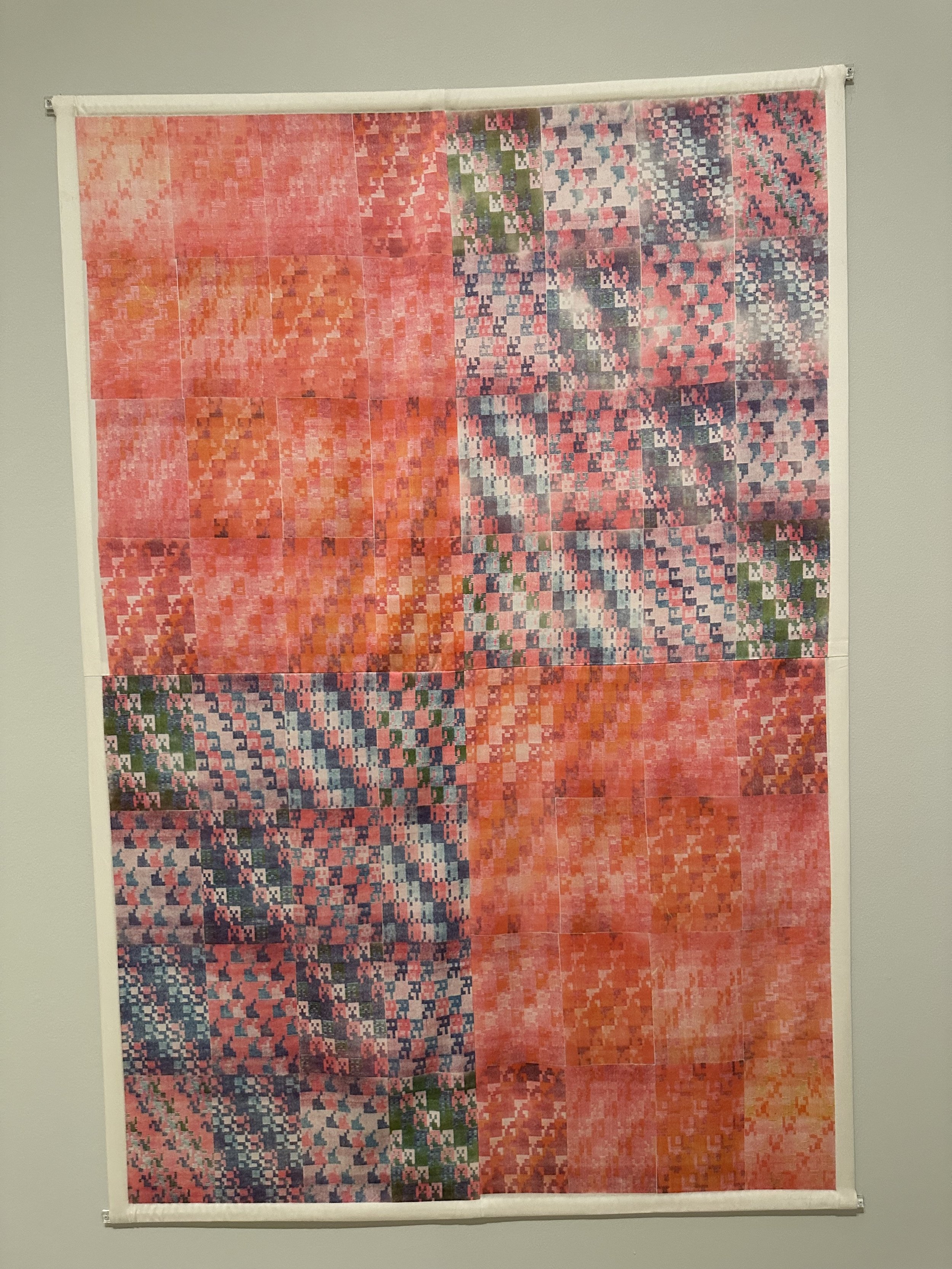

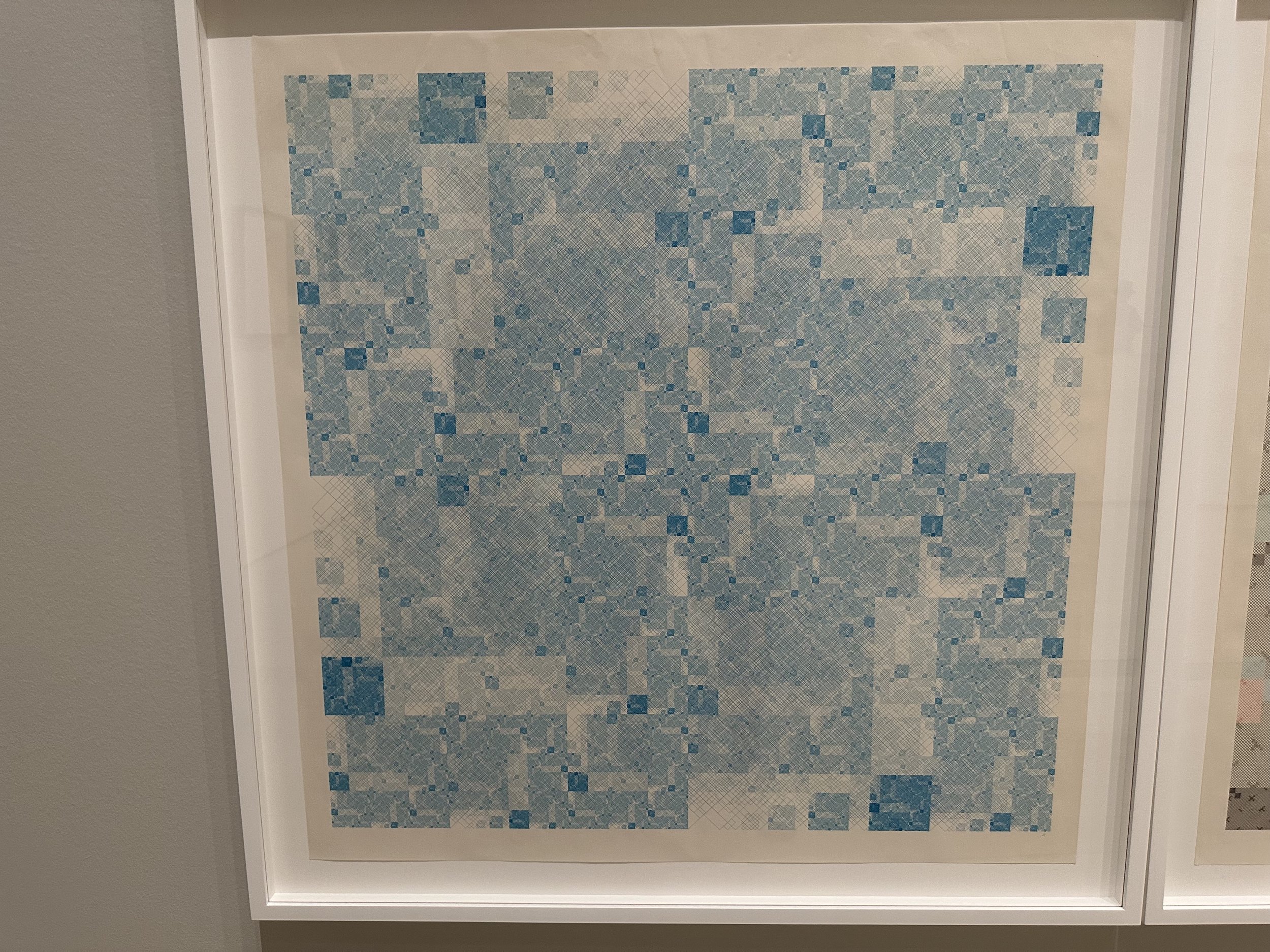

One notable exhibition of Kjetil's work took place at Kate Vass Galerie in 2020, featuring him in the "Game of Life - Emergence in Generative Art" exhibition. This show served as a tribute to the late mathematician John Horton Conway, renowned for his influential "Game of Life" concept. His process results in bold works with basket weave-like patterns that resemble graphic pixelated flags or banners. These pieces recall computing origins in the Jacquard loom, a device that employed punch cards to simplify the intricate weaving process of 18th-century textiles. We believe this exhibition marked a turning point in Kjetil's career, subsequently leading to his feature in the New York Times.

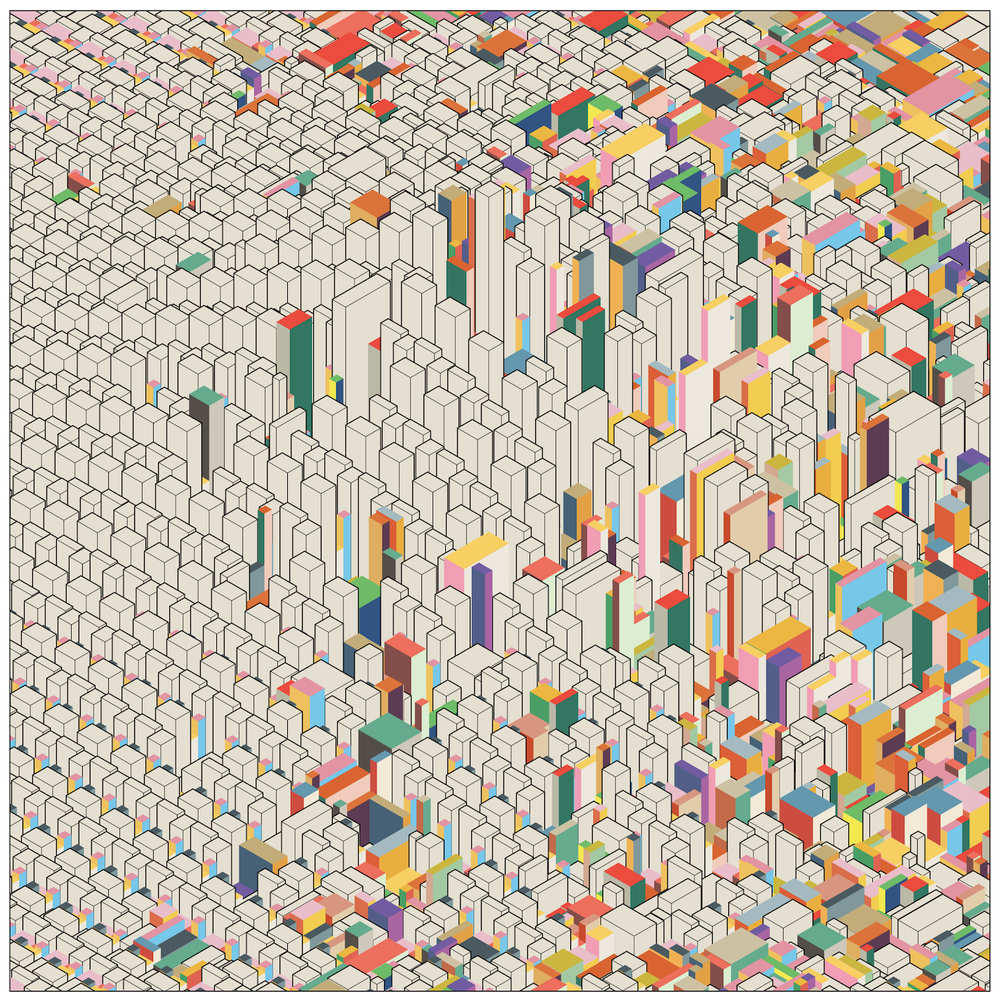

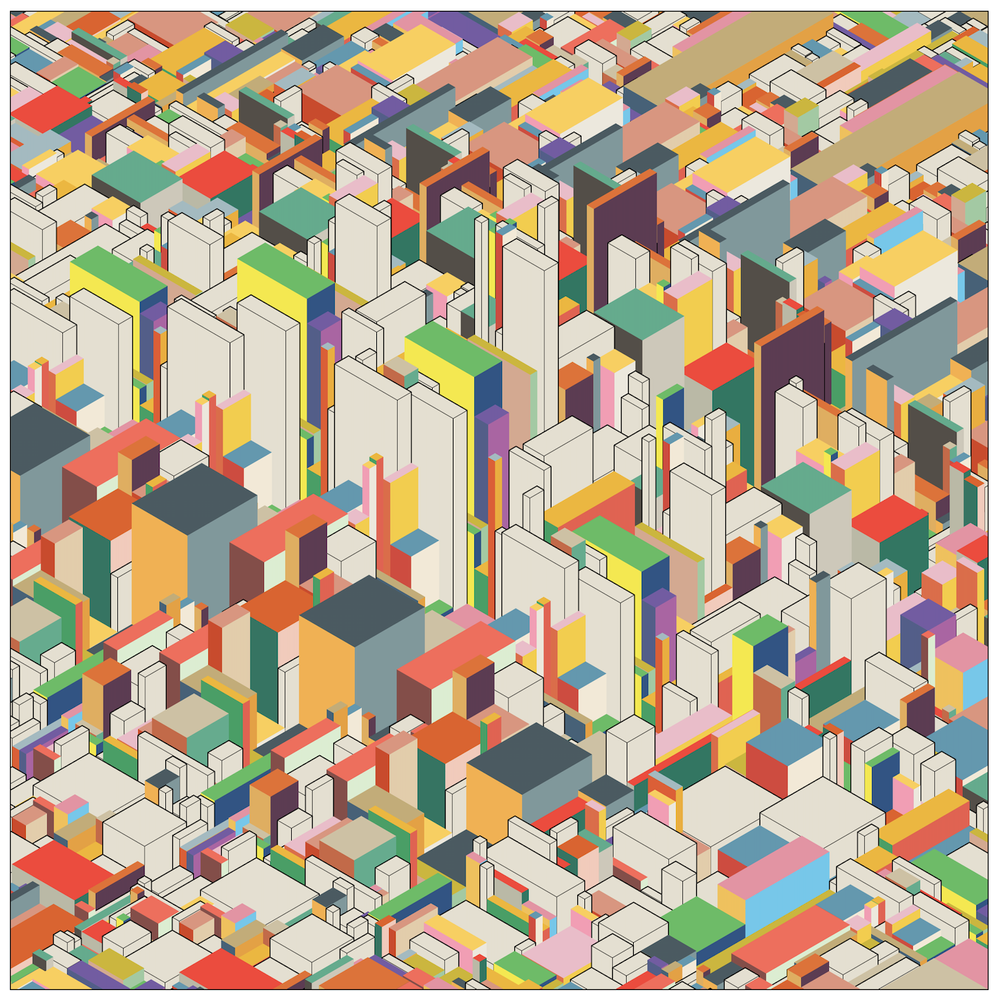

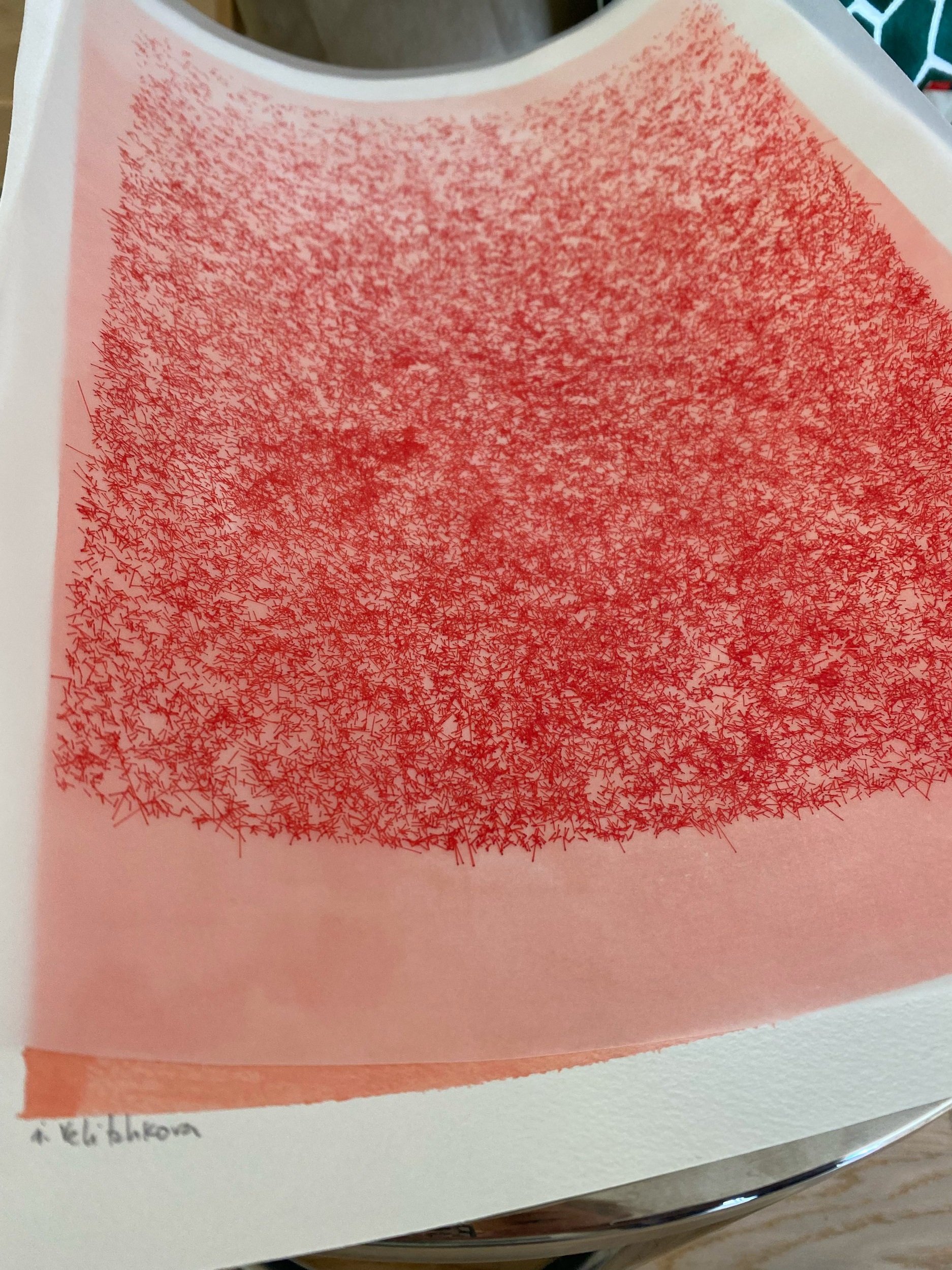

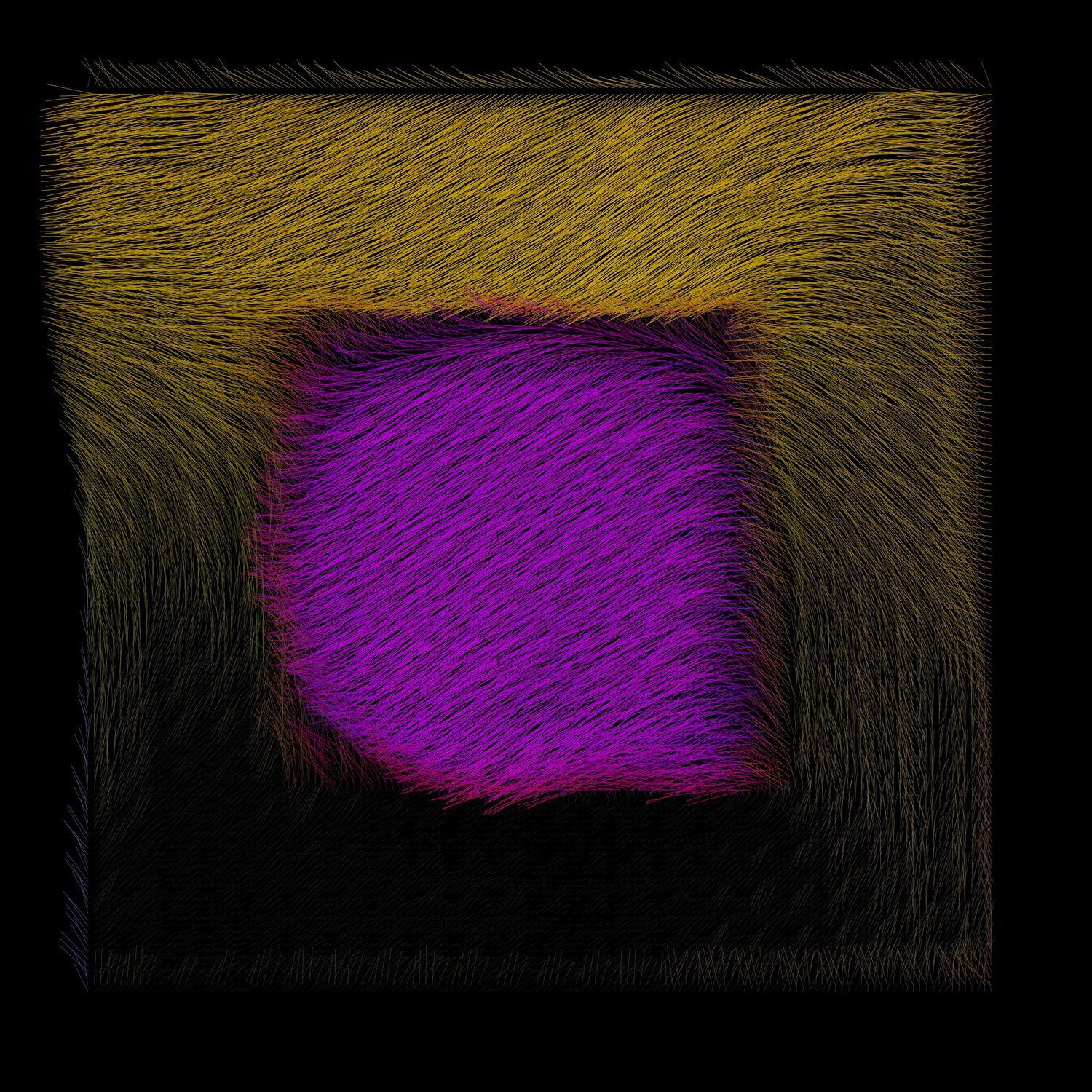

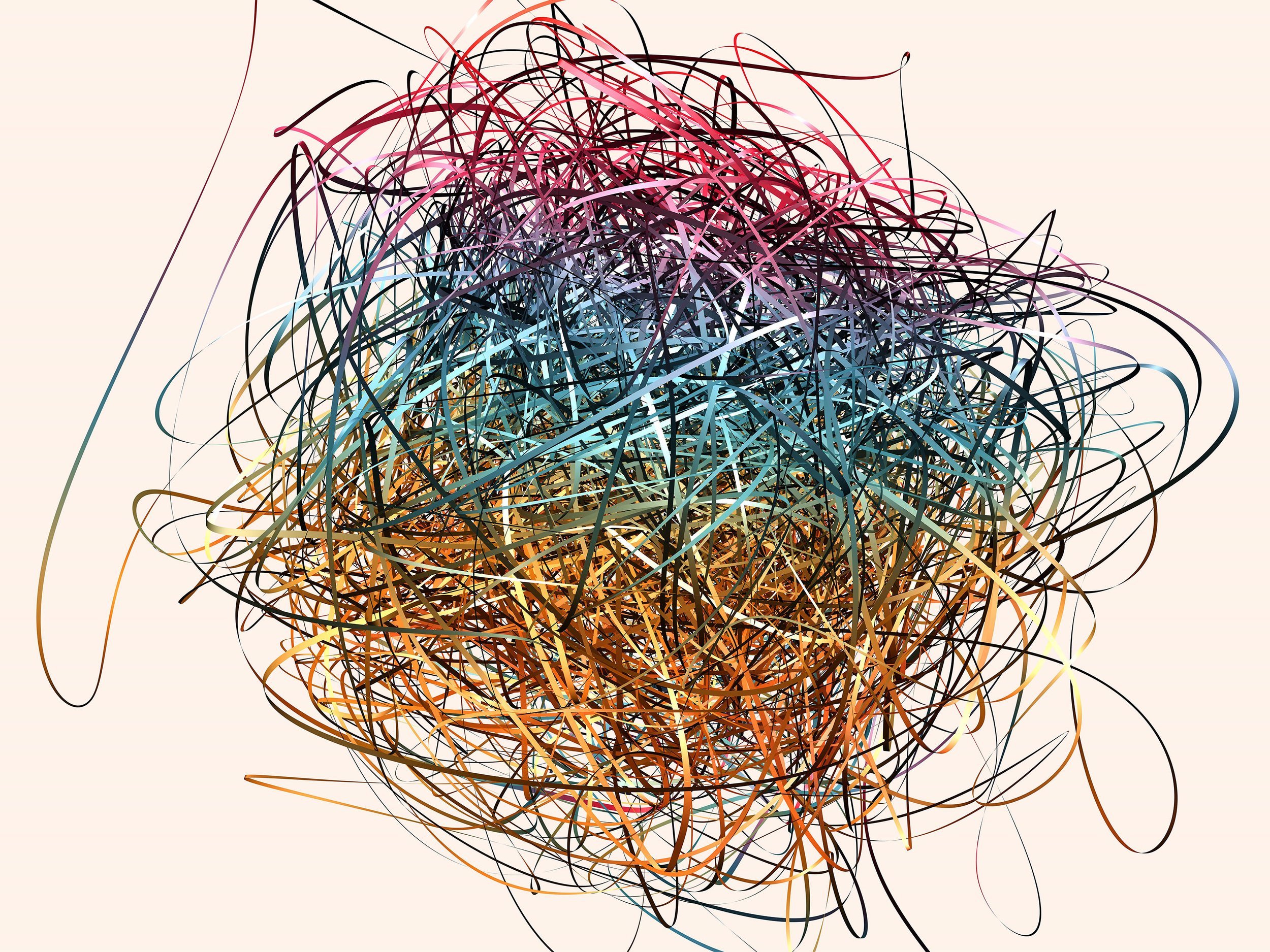

Kjetil's artistic journey reached new heights with his “Archetype” drop at Artblocks in 2021. The selected “Archetypes” were showcased at the ZKM Cube as part of the exhibition "CryptoArt It’s Not About Money," alongside other prominent NFT artworks like CryptoPunks and Cryptokitties. “Archetype” explores the use of repetition as a counterweight to unruly, random structures. As every single component looks chaotic alone, the repetition brings along a sense of intentionality, ultimately resulting in a complex, yet satisfying expression.

Kjetil's "Iterations" series made its debut at the Phygital show in April 2022 at Kate Vass Galerie. The series explores the interplay between structure and chaos, creating a visual impression of a structure by repeating random layouts of blocks. However, the process intentionally introduces imperfections and mutations to reintroduce an element of chaos. This was the first time when Kjetil accompanied his digital work with unique 1/1 signed fine art prints 120x120cm.

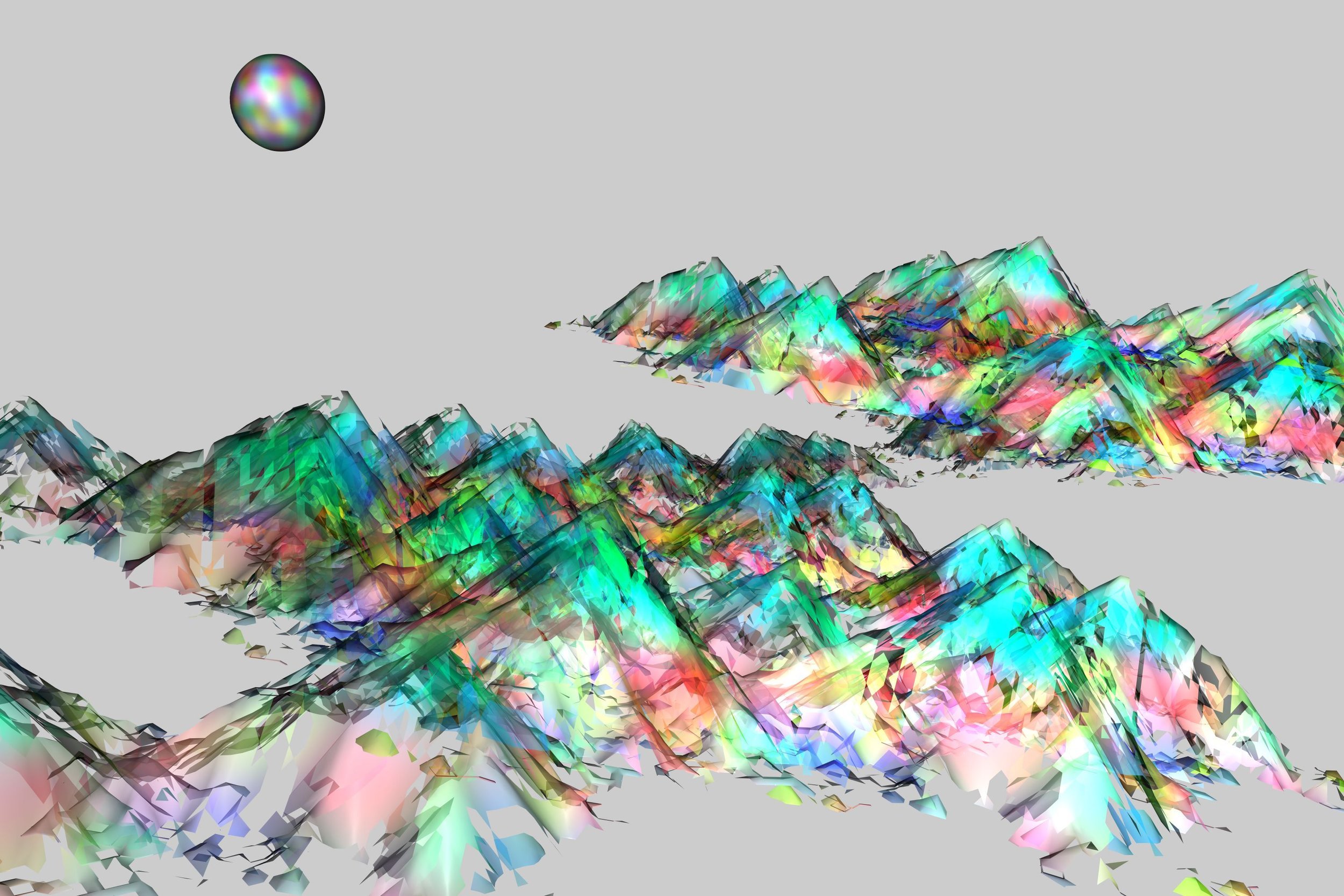

Among his notable works is "Curvescape VII – Outpost" which adds architectural elements to a previously barren landscape. The scale and nature of these structures remain enigmatic, blending the aesthetics of a free-spirited pencil with the precision of computer-generated imagery.

Later at the end of 2022, the beginning of 2023 - Kjetil's "10 EXPANSE" series made a grand entrance during the New Year's Eve auctions. Minted on his own smart contract, the series divides the plane into a grid and transforms each grid cell into cuboids of varying dimensions. The coloration of each cuboid's face is determined by its slant relative to a light source, translating geometric relationships into numerical values mapped to specific locations in the color space.

Through his inventive and boundary-pushing artworks, Kjetil Golid continues to captivate audiences with his exploration of algorithms, generative art, and the fascinating interplay between structure and chaos.

To read more about the artist and see the full portfolio of his works HERE.

More Projects

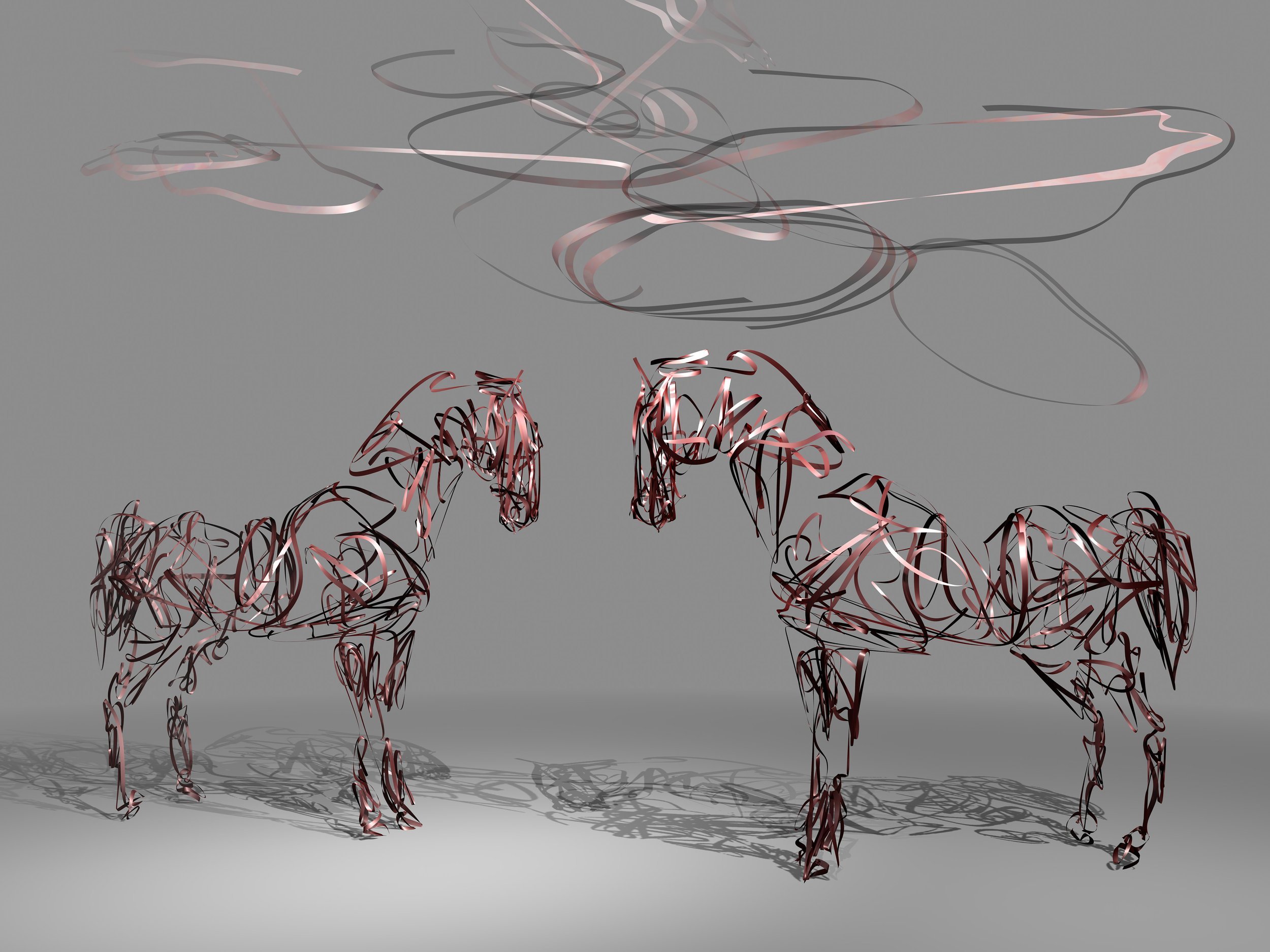

Hippodrome, 2019

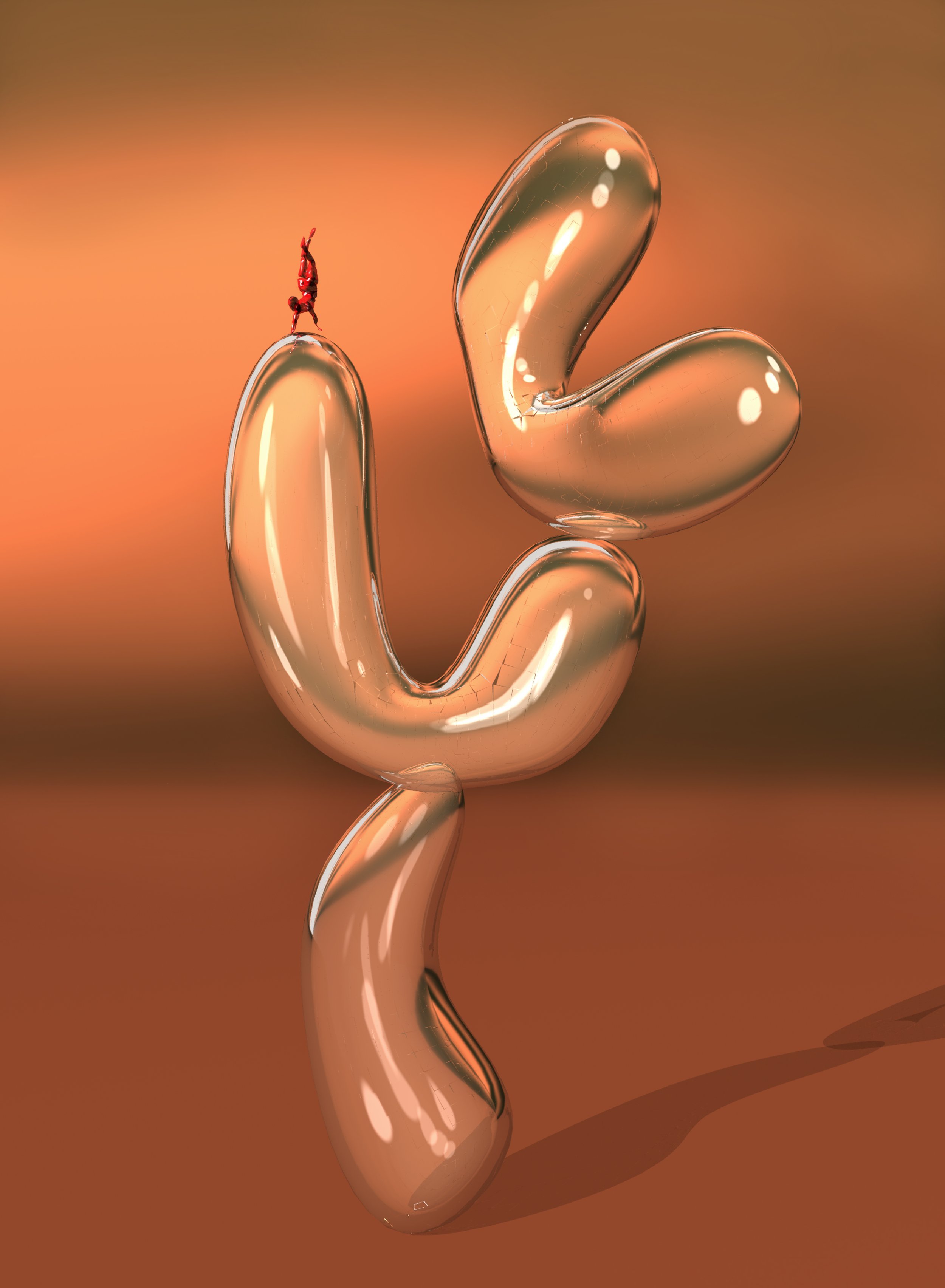

Paper Armada, 2021

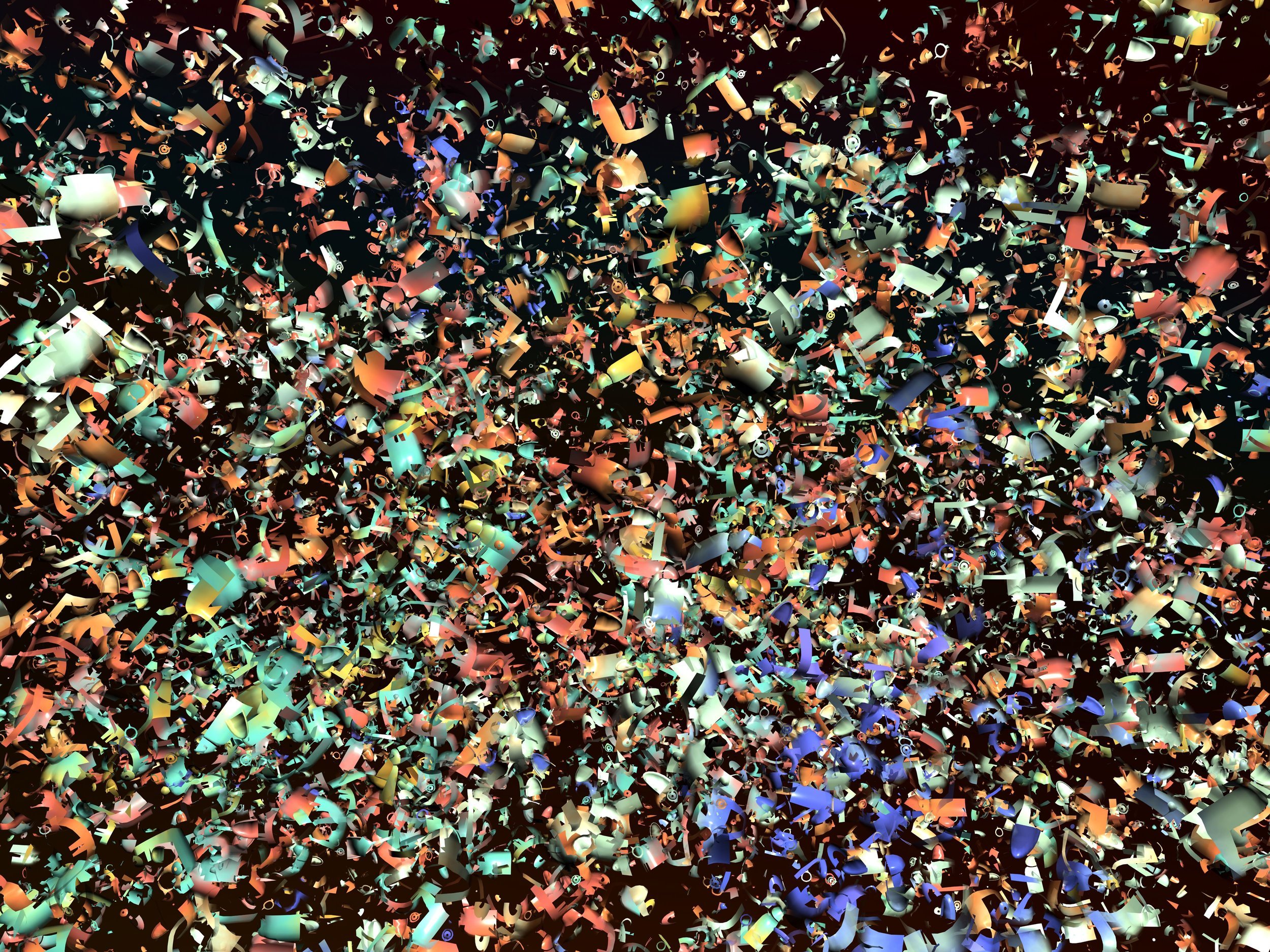

Bazaar and Aula, 2021

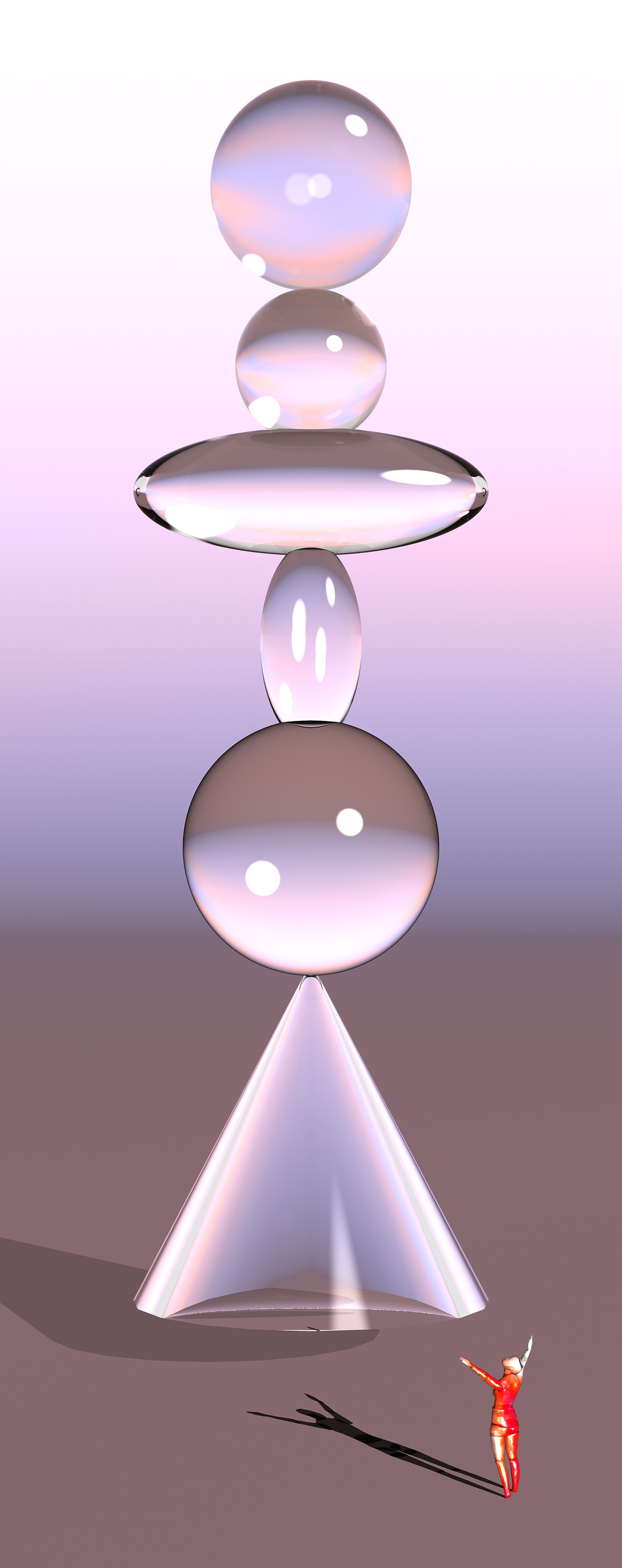

ORBIFOLD, 2023

History of AI - The new tools: ChatGPT

Let's start with last year's biggest AI sensation: ChatGPT. It is a language model developed by OpenAI. It was created to generate human-like responses to natural language and to assist in various tasks. The development started with the creation of its predecessor, GPT-1, in 2018. Since then, the San Francisco-based artificial intelligence company has been working to improve its language generation capabilities through iterative training on large datasets of text. Developers have been feeding the system large amounts of text, such as books, articles, and websites, and using this data to teach it patterns to generate coherent responses.

In recent months, the development of new AI tools has made it clear that AI has become a part of our everyday lives and is no longer restricted to the realm of research centers and tech companies. AI has gradually become a technology that businesses and individuals can use to transform the way they work and live. In our previous article, we presented the history of AI, which was first introduced in 1956 at the historical Dartmouth Conference. Now, we are excited to bring you the latest tools that showcase what AI is capable of today.

Let's start with last year's biggest AI sensation: ChatGPT. It is a language model developed by OpenAI. It was created to generate human-like responses to natural language and to assist in various tasks. The development started with the creation of its predecessor, GPT-1, in 2018. Since then, the San Francisco-based artificial intelligence company has been working to improve its language generation capabilities through iterative training on large datasets of text. Developers have been feeding the system large amounts of text, such as books, articles, and websites, and using this data to teach it patterns to generate coherent responses.

The technology

When OpenAI launched ChatGPT at the end of November 2022, they were not prepared for the huge interest it would quickly gain. However, most of the technology behind ChatGPT is not new. It is based on a technology called neural networks, designed to simulate the way the human brain works. It processes information through interconnected nodes that identify patterns and relationships in data. Neural networks date back to the 1950s, but the specific neural network architecture that ChatGPT uses, called a transformer, was developed in 2017 by Google. It quickly became a popular solution for language translation and text summarization, using a self-attention mechanism, which allows the model to focus on different parts of a text.

Another important technology is “transfer learning,” which is a type of machine learning technique where the developers reuse a pre-trained model as the starting point for a new task. While the concept of transfer learning has been around since the 1970s, it has significantly developed in recent years. It allows ChatGPT to be trained on many texts and then fine-tuned on generating chat responses or answering questions.

“Reinforcement learning” is another key component of ChatGPT. Reinforcement learning is a type of machine learning where the model learns through trial and error by receiving feedback from its environment.

The secret of ChatGPT's success lies not in inventing all these technologies, but in combining and scaling existing ones. By using techniques such as transfer learning, reinforcement learning and the neural network architecture, ChatGPT has been able to create a language model that can generate human-like responses.

The Story of Chatbots

The history of chatbots goes back decades ago. One of the earliest chatbots was called ELIZA, which was developed in the mid-1960s by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT. ELIZA was a program that simulated conversation by using pattern matching and a set of predefined responses. It was designed to mimic the conversational style of a psychotherapist and was used as a tool for studying human-machine communication.

In the 1970s and 1980s, chatbots began to be used in a variety of applications, including customer service, information retrieval, and entertainment. One popular chatbot during this time was called Parry, which was developed by Kenneth Colby in the 1970s. Parry was designed to simulate a patient with paranoid schizophrenia and was used as a tool for studying the human perception of mental illness.

In the 1990s, with the rise of the internet, chatbots became more widely used for online customer service and support. One notable chatbot during this time was ALICE, which was developed by Richard Wallace in the mid-1990s. ALICE was designed to simulate conversation with a human user and was used in customer service and information retrieval.

Overall, early forms of chatbots were developed and used for a variety of applications, including studying human-machine communication, simulating mental illness, and providing online customer service and support. The development of chatbots has paved the way for more advanced language models like ChatGPT, and I look forward to seeing how this technology will continue to evolve in the future.

The road to mainstream popularity

After the release of GPT-1 in 2018, OpenAI introduced the next model, GPT-2 in 2019, which was trained on even larger text data than its predecessor. It was capable of generating high-quality human-like text, such as news, stories, or even computer code. It quickly received a lot of attention from various industries and researchers. In 2020, OpenAI released GPT-3, which had amazing capabilities in generating coherent text and performed well in answering questions, summarising and translating. GPT-3.5 was built on this model in mid-2021 by further improving it. It also included new features such as generating texts based on specific scenarios and preventing the repetition of phrases. In May 2022, InstructGPT was introduced, which is a variation of the GPT series. It was designed to be more controllable, allowing users to provide more specific instructions. Users could guide the model by suggesting possible paths for it to follow.

OpenAI headquarters, Pioneer Building, San Francisco

While all these models were available on the company's website for developers to integrate into their own software, they did not gain mainstream popularity. However, this has changed with the emergence of ChatGPT in November 2022, which is based on the GPT-3.5 architecture and has already been adopted by millions of users.

We might ask: why did ChatGPT become the most talked-about AI model? It was one of the first AI models that were made publicly accessible and understandable to non-experts. It mimics human conversation and generates outputs in a way that humans understand and communicate. In other words, it aligns with what a human wants from a conversation AI: helpful and truthful responses, an easily accessible chat interface, and the ability to ask follow-up questions if necessary.

Users have found a variety of ways to use the model, such as creating resignation letters, answering test questions, writing poetry, or even seeking life advice. In many ways, ChatGPT can be a „virtual best friend” who can help you in many situations and even show empathy.

The limitations

ChatGPT's popularity has made it a target for users attempting to exploit its flaws. Some of these users have discovered that ChatGPT can generate unwanted outputs. OpenAI has taken action to address this issue by using adversarial training to prevent users from tricking the model into producing harmful or incorrect responses. The training involved multiple chatbots against each other, with one chatbot trying to generate a text that will force another chatbot to produce unwanted responses. The successful attacks are added to the training data so that the model can learn to ignore them.

ChatGPT also has other limitations, that could be improved. Like any other language model, Chat GPT can contain biases and stereotypes that may be offensive to specific individuals. It also has limited knowledge of events that happened after September 2021, and it is not able to answer questions about specific topics or new developments in a particular field. It may also have difficulty understanding context, especially carcasm, and humor. If the user uses sarcasm in their message, the model sometimes fails to understand the meaning of that and responds incorrectly. Even though ChatGPT can generate empathetic responses, it cannot provide truly empathetic responses in all situations.

ChatGPT-4 and the future

OpenAI has updated the system several times since its launch. The latest update occurred on the 14th of March 2023, when ChatGPT-4 was released. This latest version is capable of solving even more complex problems, better understanding and reasoning about the context of conversations and generating even more human-like responses quickly and accurately. In addition to improving its capabilities, the developers have also made it a priority to enhance its safety, making it less likely to provide harmful or incorrect answers.

In addition to its popularity among users, many big companies noticed ChatGPT capability. OpenAI has recently partnered with Microsoft and global management consulting firm Bain, known for their marketing campaigns for major companies like Coca-Cola. This partnership will allow these companies to integrate ChatGPT's language capabilities into their own products and services, further expanding the model's impact.

ChatGPT as an artistic practice

GPT chat can be used for artistic purposes in a variety of ways. As a language model, GPT chat can generate text in response to prompts or questions, and this can be used by artists to inspire their creative work.

Here are some ways in which people can use GPT chat for artistic purposes:

Writing prompts: GPT chat can be used to generate writing prompts for artists. They can provide a topic or theme, and GPT chat can generate a variety of prompts that can help the artist explore the topic from different angles. These prompts can inspire poetry, short stories, or other forms of written work.

Collaborative storytelling: GPT chat can be used to collaborate with others to create a story. Artists can start by providing a prompt or a beginning of a story, and then invite others to add to the story by typing in their responses. As the story progresses, GPT chat can use the information provided by the collaborators to generate the next part of the story.

Dialogue writing: GPT chat can be used to generate dialogues between characters. Artists can provide the context of the conversation, the personalities of the characters, and the tone of the conversation. GPT chat can then generate a dialogue that fits the context, personalities, and tone.

Character creation: GPT chat can be used to create unique characters for an artwork. Artists can describe the physical appearance, personality traits, and backstory of the character, and GPT chat can generate a detailed description of the character. This can help artists visualize the character and bring them to life in their artwork.

Poetry generation: GPT chat can be used to generate poetry in response to a given prompt. Artists can provide a theme or a set of keywords, and GPT chat can use its language generation capabilities to produce a poem that fits the theme or keywords.

Chat GPT can be combined with the tool, called ‘Mid-journey’, for example. Various AI tools can be linked to their potential to help artists and creatives in their work. While Chat GPT can generate text-based prompts, dialogues, and character descriptions that can inspire creative work, Mid-journey AI can analyze the performance of existing artworks and identify opportunities to improve them. Combining the two tools, artists can use Chat GPT to generate prompts and ideas for new artworks, and then use Mid-journey AI to analyze the performance of those artworks and make data-driven decisions to optimize them. Ultimately, by using these tools in tandem, artists can leverage the power of AI to enhance their creative process and create more successful artworks. With the continued development of AI and machine learning technologies, GPT chat is likely to become even more advanced and valuable for artistic purposes in the future.

“METAMORPHOSES" BY MISS AL SIMPSON - 100 ITERATIONS 31/05

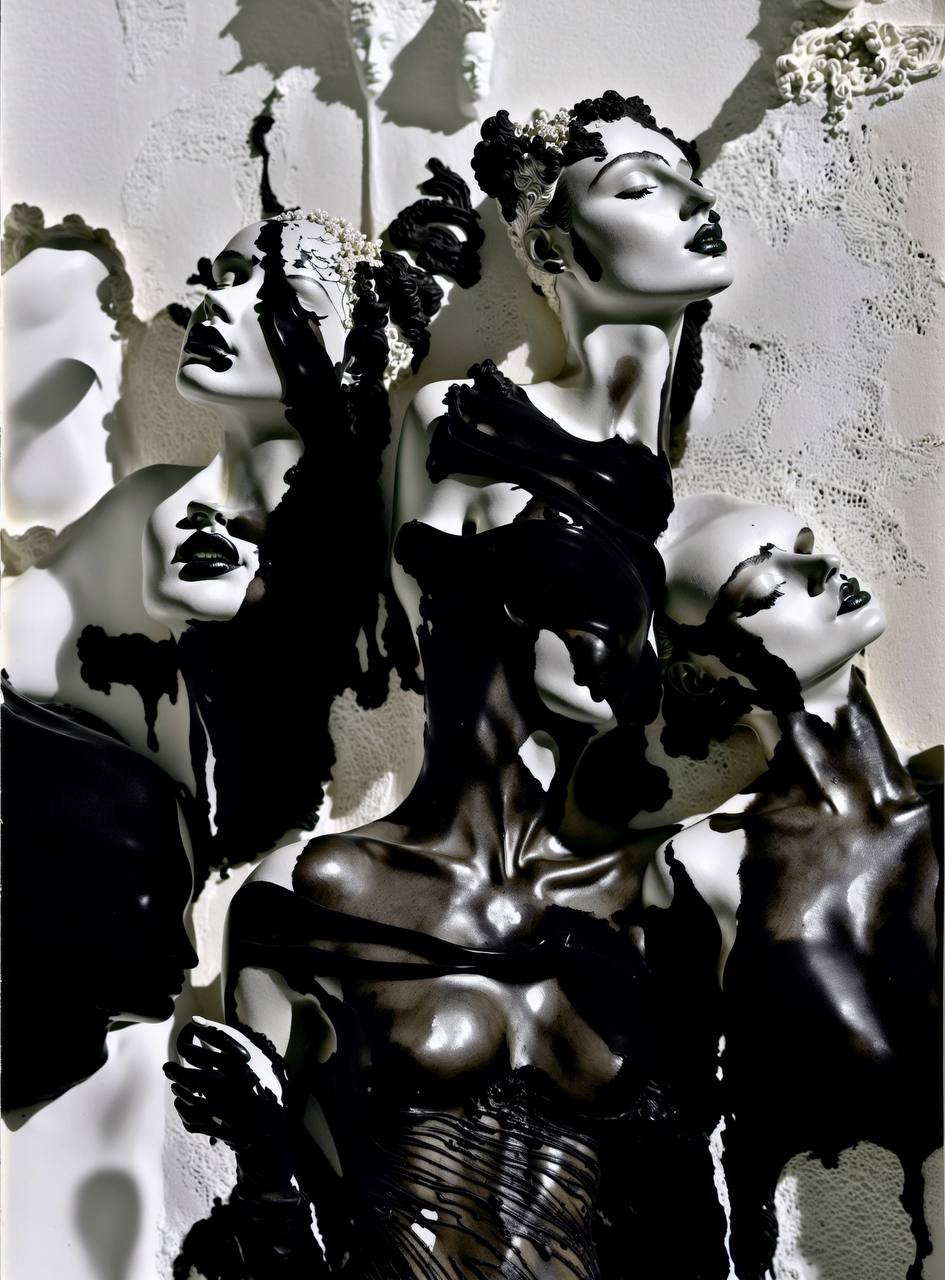

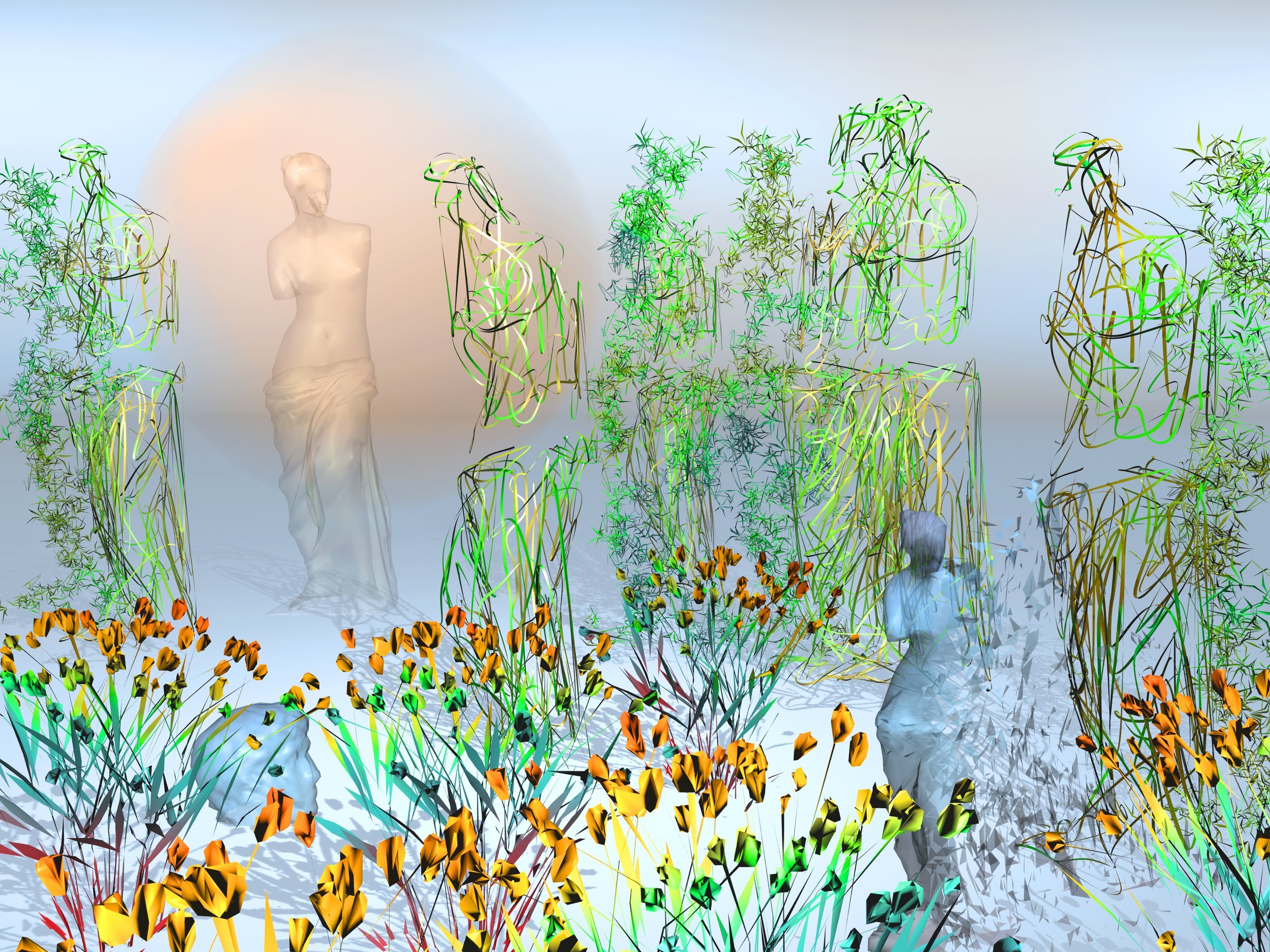

Miss AL Simpson, an award-winning crypto artist, has been at the forefront of the web3 movement since 2018. Renowned for her distinctive style, she seamlessly merges digital graffiti with animated 3D historical motifs. Notably, AL Simpson has embarked on pioneering AI collaborations that push the boundaries of traditional art paradigms. By embracing the potential of artificial intelligence as a creative partner, she redefines the future of crypto art.

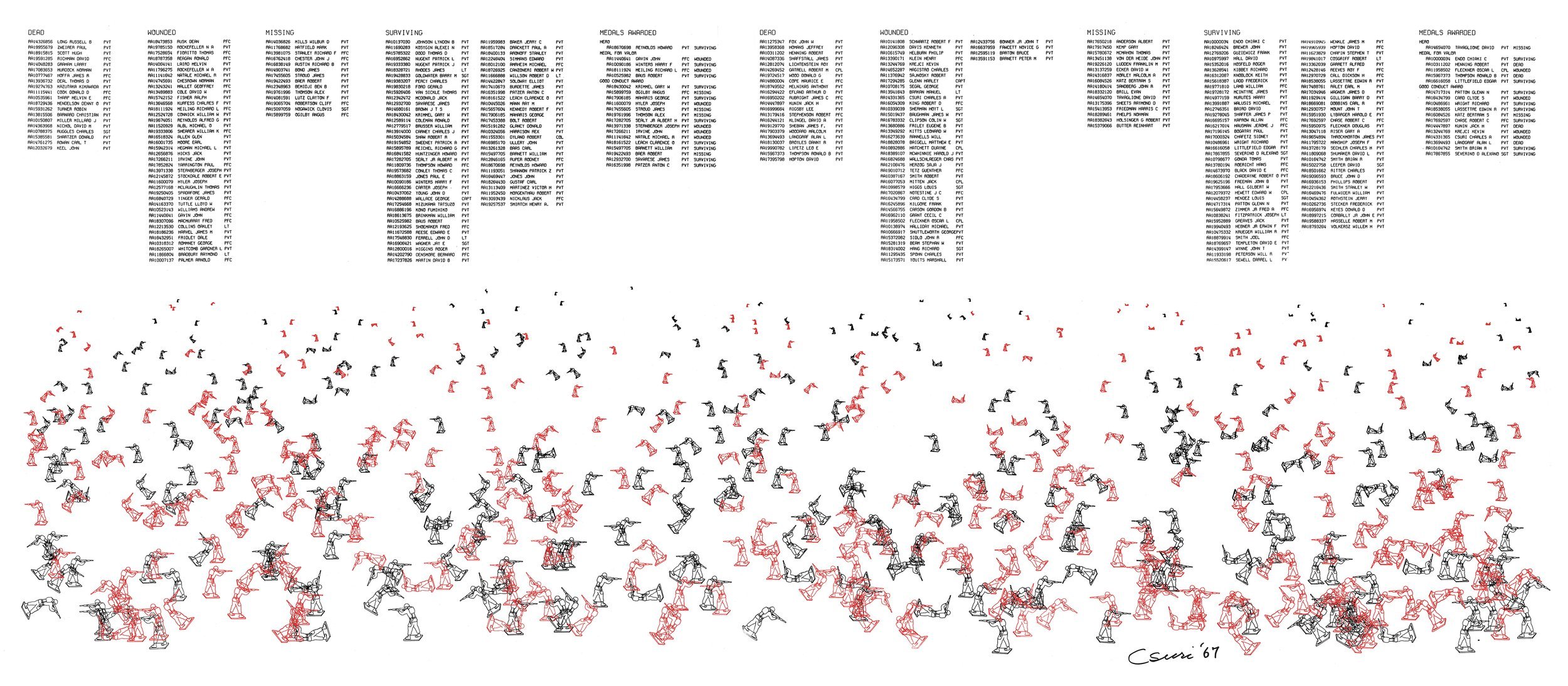

As part of the curated group exhibition "Do Androids Dream About Electric Sheep?" by Kate Vass Galerie, opening on 31/05, Miss AL Simpson presents her first AI long-form project ", Metamorphoses." This series comprises 100 unique live-generated iterations and serves as the beginning of the ongoing show. Drawing inspiration from the epic poem "Metamorphoses" by the Roman poet Ovid, Miss AL Simpson embarks on a novel approach for a long-form project. The mythological tales within Ovid's work explore themes of transformation, encompassing love, desire, power, and social and political climate, often incorporating themes of transformation and change that mirror the turbulence of our current society.

Miss AL Simpson's rendition of "Metamorphoses" is a timeless and enduring series of works. Ovid's "Metamorphoses" has profoundly influenced Western literature and art for centuries. Miss AL Simpson draws upon these timeless stories to explore the complex relationship between AI and humanity. For instance, in the tale of Narcissus, who becomes transfixed by his reflection, Simpson finds a parallel to humans fixating on the output of AI, perceiving it as conscious and relatable rather than recognizing it as the product of an algorithm. With masterful skill, she adapts the themes of transformation and the interplay between the human and AI realms, resonating with contemporary audiences. Leveraging the capabilities of 0KAI, Miss AL Simpson develops her concept by employing prompts and a combination of traits and rarities, blending the poems with her earlier analogue artwork from 2018 to create a beautiful body of work.

"Metamorphoses" will be presented as a Dutch auction on May 31, 2023, at 8 pm (CET) on https://0kai.k011.com, offering art enthusiasts an opportunity to engage with and acquire this remarkable collection.

This series of works are about the "AI commodification of consciousness" as a future concern within the context of the past through Ovid’s “ Metamorphoses”.

Written by Miss AL Simpson

ART PRACTICE - COMMODIFICATION

My artistic practice has always questioned the issue of COMMODIFICATION. Commodification is the transformation of goods, services, ideas, and people into commodities or objects of trade. I have particularly been intrigued, to-date, by the commodification of women within advertising and the COLLECTIVE CONSCIOUSNESS.

In the context of fashion magazines, women (their images, personalities, and stories) are often commodified, particularly through advertising. In many fashion magazines, the presentation of women often conforms to conventional beauty standards and societal expectations. The images, articles, and advertisements typically emphasize physical appearance, style, and consumer goods, implicitly suggesting that women should strive to achieve these standards and lifestyles. This depiction can commodify women by reducing their value to their physical appearance and consumption habits, and by promoting a specific, often unattainable, ideal of femininity. This commodification process is not just about selling products; it also sells an image, a lifestyle, and a specific set of values. Advertisers use these techniques to create a desire for their products, linking them to the attainment of the promoted ideals.

My practice (pre-AI) was always about ripping up this commodification, sometimes literally, through ripping up the magazines into collage. Sometimes by using ink, textures and paint to obliterate the fashion magazine advert completely. This was done both in an analogue and digital way. This method can be seen in a lot of my pre-AI artworks. IN this way, I have also always explored the issue of transformation.

This is one aspect of the commodification of consciousness but what is interesting is whether tokenizing NFTs is another aspect of the commodification of consciousness too. In terms of the commodification of consciousness, if we interpret consciousness broadly to include the creative and intellectual output of an individual, then the creation of NFTs based on our artistic ideas and execution could be seen as a form of commodifying consciousness. Each NFT is a tokenized version of an artistic idea, and the sale of these tokens effectively turns those ideas into commodities.

THIS PROJECT

As you can see, there is a connection with this project and my practice. Also, I like the fact that I am literally feeding my old cryptoart images (based on a similar theme) into the machine to generate new AI images.

As an artist who has explored the concept of “COMMODIFICATON” for the whole of my practice, it seemed like a natural progression to look, with a kind of futurism, to how COMMODIFICATION might look down the line. With the rapid growth of AI, I was intrigued by the concept of AI COMMODIFICATION OF CONSCIOUSNESS, both for its mystery but also for what it might mean for humans. I thought that it might be interesting to explore this transformative idea by looking at past mythology through the eyes of Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses” which is all about transformation.

The AI Commodification of Consciousness refers to the idea of artificial intelligence technologies being developed to a point where they can replicate, simulate, or even surpass human consciousness, with this capacity being bought, sold, and traded as a commodity. This raises a host of ethical, philosophical, and socio-economic questions, including the nature and value of consciousness, the ethical treatment of artificial entities, and the potential consequences of creating and distributing such technology.

"Metamorphoses" is a Latin narrative poem by the Roman poet Ovid, completed in 8 CE. It is an epic exploration of transformation and change in mythology, ranging from the creation of the world to the deification of Julius Caesar.

With this project “Metamorphose”, I have brought together all three aspects into one:

1. Commodification

2. Transformation

3. Relating the other two concepts to a future where AI and Humans work hard find out what that means for our Consciousness.

I wanted to keep some reference to my early roots of exploration of this field so there is an AI interpretation of ripped Vogue magazine textures and dripping black ink. However, are the figures Greek figures from Ovid or are they future AI metaphors? That is for the viewer to decide.

DETAILS OF THE PROJECT

1. Pygmalion and the Statue (Book X): Pygmalion sculpts a woman out of ivory that is so beautiful and lifelike he falls in love with it. He prays to Venus to bring the statue to life, and his wish is granted. This story relates to AI in that we are creating something artificial (the statue/AI), that could become 'alive' in a metaphorical sense (consciousness). It brings up questions about the creation of artificial life and love for the artificial.

2. Daedalus and Icarus (Book VIII): Daedalus, a skilled craftsman, creates wings for himself and his son Icarus to escape from Crete. Icarus flies too close to the sun, melting his wings and causing him to fall into the sea and drown. This story brings up themes of human hubris, the misuse of technology, and unintended consequences, all of which are relevant to AI development.

3. Echo and Narcissus (Book III): As I detailed in the previous responses, this tale's themes of self-love, replication, and the inability to return love can all be related to AI commodification of consciousness.

4. Tiresias (Book III): Tiresias was transformed from a man into a woman, and then back into a man. This could be used to discuss the fluidity and transformation of identity, a relevant theme when considering how AI might assume various roles and identities.

5. Arachne and Minerva (Book VI): Arachne, a skilled mortal weaver, challenges the goddess Minerva to a weaving contest. Despite Arachne's undeniable skill, Minerva transforms her into a spider for her hubris. This tale could be related to AI, questioning how far we can push our technological 'weaving' before we incur unforeseen consequences.

NARCISSUS AND ECHO

In the story of Narcissus and Echo from Ovid's "Metamorphoses", a critical moment and line that encapsulates the tragedy of Narcissus is:

"quis fallere possit amantem?"

This line translates to "Who could deceive a lover?"

This line comes from the following context in Book III (lines 339-510), where Narcissus sees his own reflection in the pool and falls in love with it, not realizing it's his own image:

"stupet ipse videnti, seque probat, nitidisque comis, lucidus et ore. qui simul adspexit, simul et notavit amantem; quodque videt, cupit, et, quae petit, ipse recusat, atque eadem adspiciens perituraque desiderat ora, ignarusque sui est. incenditque notando, utque sitim, quae non sitiat, bibendo movet.

. . .

manibusque sua pectora pellit, et illas rubet ire vias, et rubet ire vias, tactaque tangit humum lacrimis madefacta suis. . . . quis fallere possit amantem?"

Translated, these lines convey:

"He wonders at himself, and stirs the water, and the same form appears again. He does not know what he sees, but what he sees kindles his delight. He sees himself in vain, and thinks what he sees to be nothing. He himself is the object that he burns for, and so he both kindles and burns in his desire.

. . .

He struck his naked body with hands not strong for the purpose. His chest reddened when struck, as apples are wont to become, or as the purple surface of a grape, when it is pressed with the finger, before it is ripe for the table. . . Who could deceive a lover?

In the line "quis fallere possit amantem?", Narcissus is so consumed with his own image that he fails to recognize the deception – the lover he sees is himself. It demonstrates the destructive power of self-love and obsession, and could be related to AI in the sense of our societal narcissism and infatuation with our own technological prowess, to the point that we might fail to perceive the pitfalls and risks of creating machines that mimic or surpass our own cognitive abilities.

PYGMALION AND GALATEA

The key Latin line from Ovid's "Metamorphoses" that encapsulates the moment of transformation when Pygmalion's ivory statue (later known as Galatea) becomes a living woman is as follows:

"corpus erat!"

This line translates to "It was a body!"

This short exclamation is found in Book X, line 243. The full context is as follows (lines 238-243):

"oscula dat reddique putat loquiturque salutatque, et credit tactis digitos insidere membris, et metuit, pressos veniat ne livor in artus, et modo blanditias adhibet, modo grata puellis munera fert illi, conchas teretesque lapillos et volucres et mille modis pictas anseris alas."

Translated, these lines convey:

"He gives it kisses and thinks they are returned; he speaks to it; he holds it, and imagines that his fingers sink into the flesh; and is afraid lest bruises appear on the limbs by his pressure. Now he brings presents to it, such as are pleasing to girls; shells, and pebbles, and the feathers of birds, and presents of amber."

The sentence "corpus erat!" (line 243) comes after these lines, and it is the moment when Pygmalion realizes that the statue has transformed into a living woman. He can feel warm flesh instead of the cold ivory he had sculpted, marking the incredible transformation from inanimate object to living being. It is this moment that relates most strongly to the concept of artificial intelligence, particularly the point at which AI might become indistinguishable from human consciousness.

DAEDALUS AND ICARUS

The story of Daedalus and Icarus in Ovid's "Metamorphoses" provides one of the most iconic cautionary tales in literature. Here's a key Latin line from the tale found in Book VIII:

"ignarus sua se quem portet esse parentem."

Roughly translated, it means "unaware that he is carrying his own downfall."

The line comes from the following larger context (lines 183-235), where Daedalus warns his son, Icarus, about the dangers of their flight:

"medio tutissimus ibis. neu te spectatam levis Aurora Booten aut Hesperum caelo videas currens olivum: temperiem laudem dixit. simul instruit usum, quale sit iter facias monstrat, motusque doceri.

. . .

ignarus sua se quem portet esse parentem."

Translated, these lines convey:

"You will go most safely in the middle. Lest the downy Bootes, seen by you, or Helice with her son, or Orion with his arms covered with bronze, draw you away, take your way where I lead; I command you! We go between the sword and the late-setting constellation of the Plough. Look not down, nor summon the constellations that lie beneath the earth, behind you; but direct your face to mine, and where I lead, let there be your way. I give you to these to be taken care of; and, although I am anxious for my own safety, my chief concern is for you, which doubles my fear. If, as I order, you control your course, both seas will be light to me. While he gives him advice, and fits the wings on his timid shoulders, the old man's cheeks are wet, and his hands tremble. He gives his son a kiss, one never to be repeated, and, raising himself upon his wings, he flies in advance, and is anxious for his companion, just as the bird, which has left her nest in the top of a tree, teaches her tender brood to fly, and urges them out with her wings. He bids him follow, and directs his own wings and looks back upon those of his son. Some angler, catching fish with a quivering rod, or a shepherd leaning on his staff, or a ploughman at his plough-handle, when he sees them, stunned, might take them for Gods, who can cleave the air with wings. And now Samos, sacred to Juno, lay at the left (Delos and Paros were left behind), Lebynthos, and Calymne, rich in honey, upon the right hand, when the boy began to rejoice in his daring flight, and leaving his guide, drawn by desire for the heavens, soared higher. His nearness to the devouring Sun softened the fragrant wax that held the wings: and the wax melted: he shook his bare arms, and lacking oarage waved them in vain in the empty air. His face shouting 'Father, father!' fell into the sea, which from him is called the Icarian. But the unlucky father, not a father, said, 'Icarus, where are you? In what place shall I seek you, Icarus?' 'Icarus' he called again. Then he saw the feathers on the waves, and cursed his arts, and buried the body in a tomb, and the island was called by the name of his buried child."

In the line "ignarus sua se quem portet esse parentem," Daedalus is unaware that he carries his own sorrow, or his own downfall. This is a poignant moment, highlighting the tragic nature of technological overreach, which is a highly relevant theme when discussing the potential risks and dangers associated with artificial intelligence.

ARACHNE AND MINERVA

In the tale of Arachne and Minerva (also known as Athena) from Ovid's "Metamorphoses", a significant line that illustrates the central conflict and subsequent transformation is:

"mutatque truces voltus et inpendit Arachnen."

This translates to "She changes her savage expression, and attacks Arachne."

This line is found within the following larger context in Book VI (lines 1-145), where Arachne, a mortal weaver, dares to challenge the goddess Minerva to a weaving contest:

"quod tamen ut fieret, Pallas sua tela removit, quaeque rudis fecerat, laesaque stamina vellis corripuit virgaque truces acuit iras, mutatque truces voltus et inpendit Arachnen."

Translated, these lines convey:

"However, so that it might be done, Pallas removed her own web, and the threads that the unskilled woman had made, and had spoiled with her fleece; and she struck Arachne's impudent head with her hard boxwood shuttle, and attacked her with it. And Arachne was afraid, and she grew pale."

Following this, Minerva turns Arachne into a spider for her hubris, forcing her to weave for all eternity. This story is a cautionary tale about the consequences of challenging the gods, or in a broader sense, transgressing natural or established boundaries.

When applying this to AI, it could be interpreted as a warning about the potential dangers of challenging the natural order with our technological creations. Just as Arachne faced consequences for her hubris in challenging a god, we may face unforeseen consequences in our pursuit of creating machines that mirror or even surpass human intelligence. The transformation of Arachne into a spider can symbolize the transformation of society and individuals through the advent of artificial intelligence.

TIRESIEAS

In the story of Tiresias in Ovid's "Metamorphoses", a key Latin line that captures his transformation from man to woman and back to man again is:

"Corpora Cecropius rursus nova fecit in artus."

This line translates to "Again he made new bodies with his Cecropian hands."

This line comes from the larger context in Book III (lines 316-338), where Tiresias experiences his unique transformations:

"... si qua est fiducia vero, tu mihi, qui volucres oras mutaris in illas quas petis, et gemino reparas te corpore, Tiresia, dic' ait 'o, melior, cum femina sis, an auctor cum sit amor nostri?' Tiresias 'quamquam est mihi cognitus error,' dixit 'et ante oculos, ut eram, non semper adesse, nec male Cecropias inter celeberrima matres versatus, septemque annos effecerat illa. octavo, ad veterem silvis rediere figuram, et cecidere nova forma pro parte virili. saepe, puer, plena vitam sine femina duxi, saepe meis adopertus genitalibus ignes persensi, multoque tui tunc artior ignis. corpora Cecropius rursus nova fecit in artus, omnibus ut feminae cessissent partibus illi; tuque, puer, neque enim est dubium, tibi magis uror.' "

Translated, these lines convey:

" ... if there is any confidence in the truth, you tell me, who transform the wings that you seek into those that you have, and repair yourself with a double body, Tiresias, whether, when you are a woman, or when the author of our love is, is better. Tiresias replied, 'Although I am known to be mistaken, and not always to be before my eyes, as I was, nor to be badly among the most famous mothers of Cecropia, and that woman had completed seven years. In the eighth year, they returned to their old figure in the woods, and their new shape fell away in the male part. Often, boy, I have lived a life without a woman, often I have felt fires covered by my genitals, and your fire is then much tighter. Again he made new bodies with his Cecropian hands, until all parts of that woman had given way to him; and you, boy, for there is no doubt, I burn for you more.' "

Tiresias, having lived as both a man and a woman, is asked by Jupiter and Juno to settle a dispute over which gender derives more pleasure from love. His unique experience of transformation and identity can be related to AI in terms of how artificial intelligence can assume various roles and identities, providing unique insights that may not be accessible to humans. This can open up discussions about the fluidity and adaptability of AI, and its ability to take on diverse perspectives and functions.

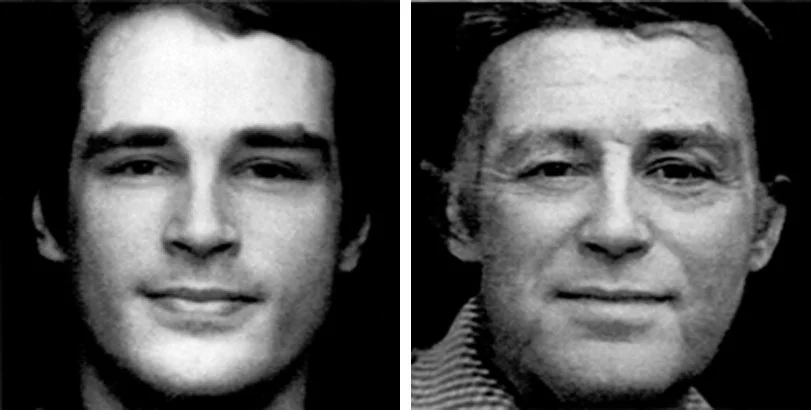

MORPHING BEYOND THE SURFACE: THE ART OF NANCY BURSON'S DIGITAL PORTRAITURE

Nancy Burson is an American artist and photographer born in 1948. She is best known for her pioneering work in computer morphing technology and is considered to be the first artist to apply digital technology to the genre of photographic portraiture. Utilizing the morphing effects she developed while she was at MIT, Burson has incorporated these techniques in various ways throughout her career including age-enhancing techniques, the creation of composite portraits, and the development of race-related works. Many people may recognize some of her creations, even if they aren’t familiar with her name. Some of her most recognizable works include the digitally morphed “Trump/Putin” on the cover of Time magazine, and the updates of missing children's portraits on milk cartons.

We can see her art in museums and galleries such as the MoMA, Metropolitan Museum, Whitney Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Center Pompidou in Paris, the LA County Museum of Art, and the Getty Museum among others. She was a visiting professor at Harvard and a member of the adjunct photography faculty at NYU for five years.

In this article, we will focus on Burson's morphing technique, presenting how she used this technology in different ways throughout her career. We will showcase her works and discuss why her art is important in the history of digital art and portrait photography. This article will include an exclusive interview with Nancy Burson herself. Burson shares her inspirations and the creative process behind her work, as well as discusses her past and personal reflections on her art with Kate Vass.

Morphing technology

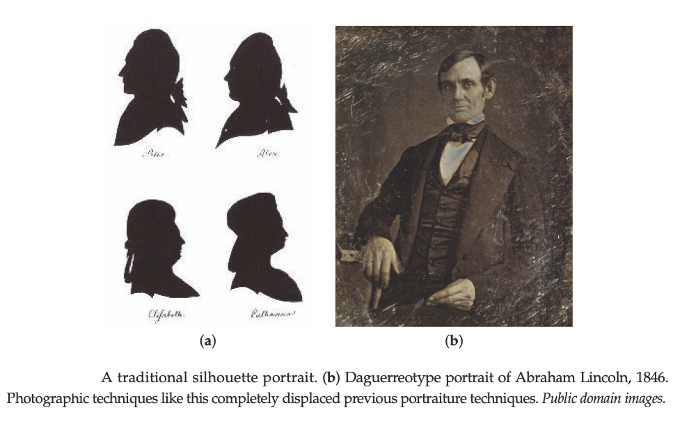

Motion pictures and animations often use morphing techniques to create a seamless transition between two images. It is a geometric interpolation technique that has been around for a long time, with traditional methods like tabula scalata and mechanical transformations. Besides these techniques, probably the most effective way to morph images was through “dissolving”, which was developed in the 19th century. Dissolving is a gradual transition from one projected image to another, for instance, a landscape dissolving from day to night. This technique was groundbreaking in the 19th—early 20th century, proving the potential of visual effects in motion pictures.

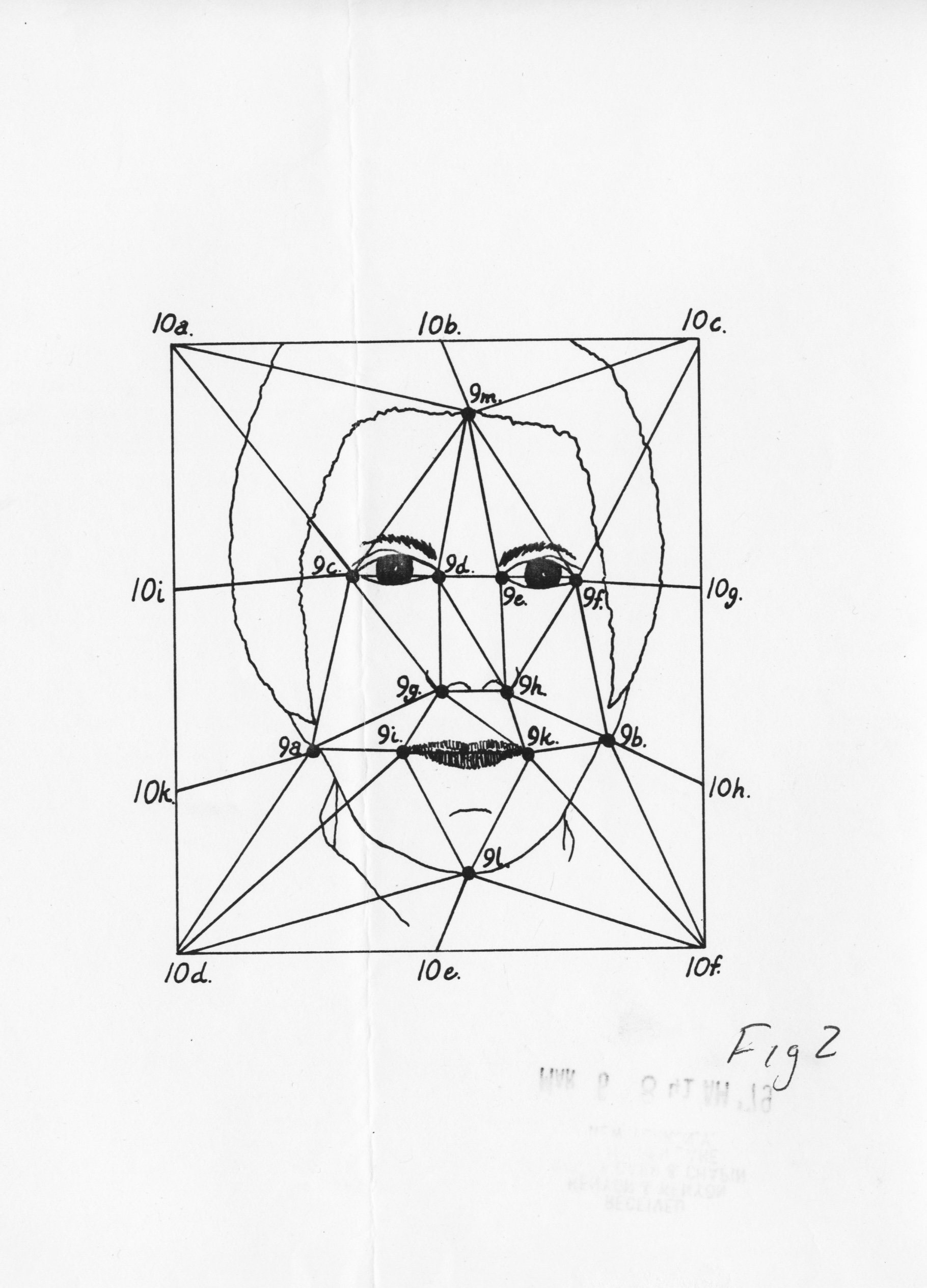

Computers replaced dissolving since the 1980s and have made morphing more convincing than ever before. Digital morphing involves distorting one image at the same time as it fades into another by making corresponding points and vectors on the before and after images. For example, we can mark key points on a face, such as the corners of the nose or the location of the eyes, and also mark these points in the second picture. The computer then distorts the first face to match the shape of the second face while gradually blending the two.

One of the first companies that used digital morphing techniques was the computer graphics firm, Omnibus. It used this technique first for commercials and then for movies. It contributed to a film called "Flight of the Navigator" which featured scenes with a computer-generated spaceship that appeared to change it’s shape. Bob Hoffman and Bill Creber were the developers of that software. Later, morphing techniques have mainly been used in the film industry. Morphs appeared in movies like “Willow” (1988), “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” (1989), and “Terminator 2: Judgment Day” (1991). In 1992, Gryphon Software developed the first morphing software, called MORPH, designed exclusively for personal computers.

Morphing Technology in Art

Nancy Burson is widely regarded as the first artist to use digital technology to create composite portraits in the early 1980s. However, prior to this, composite images were created through analog techniques by overlaying multiple images to blend and create a single image. Artists like Francis Galton and William Wegman made significant strides toward analog composite images before the arrival of digital technology.

In the 1870’s, Francis Galton first applied compositing techniques for the purpose of visualizing different human “types”. He tried to determine whether specific facial features could be associated with distinct types of criminality. Galton used multiple exposures to create composite photographs of different segments of the population, including mentally ill and tuberculosis patients as well as what he regarded as the "healthy and talented" classes, such as Anglican ministers and doctors.

Later, William Wegman continued this tradition by creating composite images in his artistic practice in 1972. His piece, "Family Combination" compared a photograph of himself with the genetic combination of his parents. He used two negatives simultaneously, one of his mother and one of his father, to create one image.

Nancy Burson: “I remember seeing Wegman’s Family Combinations when I was already working with MIT. And I didn’t find out about Galton until I was already making my own composites. It was a shock in that Galton was responsible for Eugenics, or the science of you are what you look like. I was horrified at the thought of anyone thinking that my composites were done with the same line of racist thinking. However, when they were first shown at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in 1985, it did seem that people understood my images had a light heartedness to them.”

Nancy Burson’s development

St. Louis-born Nancy Burson moved to New York in 1968. She visited the exhibition, "The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age" at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which made a tremendous impact on her life. The exhibition featured moving objects and video images, which sparked Nancy's interest in technology.

N.B.: “What I liked best about the Machine show at MoMA was that some of the pieces were interactive. The idea that viewers could participate in the art was huge and quite memorable for me. It turned the museum into a fun experience and not just a cultural one. The pieces that stuck with me the most were Nam June Paik’s videos presented in what I remember as dark cases. I remember that after seeing that exhibition, I began to visualize in my mind an interactive age machine in which viewers could see themselves older. I knew nothing at all about computers so I knew I’d have to find the people who did!

I grew up with a science background. My mother was a lab technician and my favorite memories of my childhood were of doing fake experiments with real blood! I put everything I could under my brother’s microscope!”

Nancy met early computer graphics consultants through artist’s Robert Rauschenberg’s (known for his collages that incorporate everyday materials) and Billy Klüver's (video artist) organization, Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT). Rauschenberg and Klüver had worked together with scientists to organize the “9 Evenings” performances that took place at the 69th Regiment Armory in NYC in 1966. They established the non-profit EAT that same year. EAT was pairing artists together with scientists and Nancy was paired with an early graphics specialist who informed her the technology to produce aged images was years in the future. In the interim, Burson turned to painting and in 1976, it was suggested she contact Nicholas Negroponte, the head of MIT’s Architecture Machine Group, later called The Media Lab. They had just hooked up a camera to a computer which was an early version of a digitizer or scanner. It was one of the first times that a computer interacted with a live version of a face. It took five minutes to scan a live face and subjects had to lie underneath the copy stand and be told when they could blink.

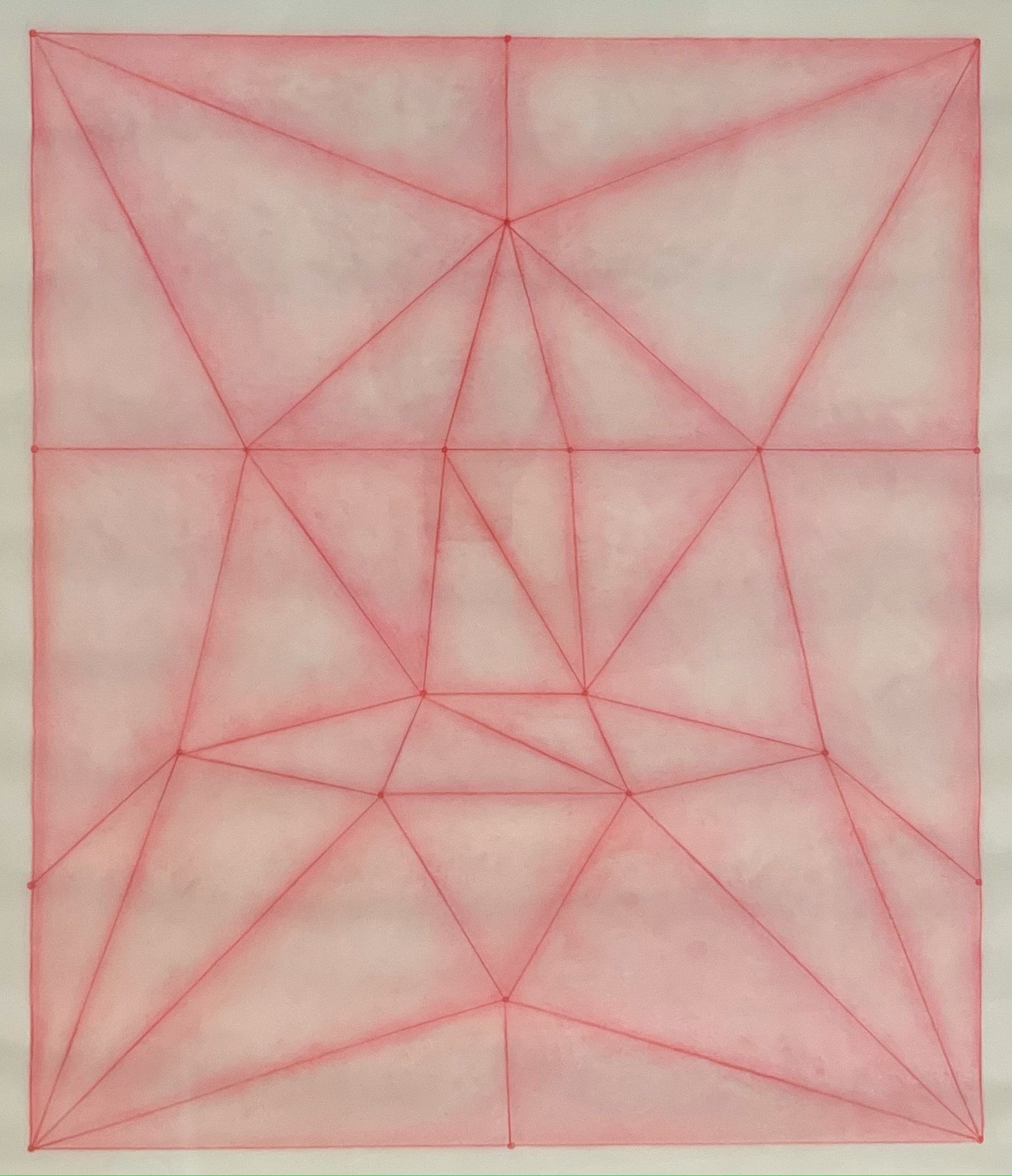

The set up at MIT which was their first version of a digitizer

Originally, she thought her idea would only be useful beyond an art context for its potential usage in cinematic special effects. However, she soon realized that the technology she developed was more useful than she initially thought. By 1981, Nancy was issued a patent for her aging machine, “The Method and Apparatus for Producing an Image of a Person’s Face at a Different Age.”

N.B.: “In my initial meetings with MIT, I was paired with a collaborator, Thomas Schneider. The project was dubbed ATE, an homage to its first beginnings from EAT. It was Tom’s design for the triangular grid which still remains the standard morphing grid in the industry today for everything from sophisticated AI software to SnapChat. When I left MIT in 1978, Tom and I became co-inventors, and he turned over his rights to me. In 1979, I was invited to present my initial video of three faces aging that were the result of my work with MIT at the annual SIGGRAPH computer graphics conference. It was that conference that first exposed the new facial morphing technologies to everyone who was to become anyone in the industry, including those who became the graphics specialists at Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) and Pixar films.

Through my former colleagues at MIT, I continued my work with two computer graphics specialists working for Computer Corporation of America, Richard Carling and David Kramlich. We fashioned our early morphing sequences into funny video presentations that were shown in the SIGGRAPH film shows in 1983 and 1984, further exposing the technology to everyone in the industry. And it was Richard, David, and I who collaborated on my first book called Composites: Computer-Generated Portraits published in 1986.”

Early works (1976–1999)

To facilitate the development of the software being built by MIT from 1976 to 1978, Burson created a self-portrait series, “Five Self-portraits at Ages 18, 30, 45, 60, and 70” in which she documented her own future aging process. She collaborated with a makeup artist to transform her face using make up to the ages of 18, 30, 45, 60, and 70. It was that study that informed how the software would enable her to explore the methodologies of altering and manipulating human features. Through the 1980s, she also used digital technology to blend the faces of groups of individuals to produce Composite Portraits.

Burson often digitally combined and manipulated images of well-known individuals, such as famous politicians and celebrities. Through these images, Burson investigated political issues, gender, race, and standards of beauty. She created one of her most important works, “Warhead I” (1982), by using images of five world leaders—Ronald Reagan, Brezhnev, Margaret Thatcher, François Mitterrand, and Deng Xiaoping—proportionally weighting the image by the number of nuclear warheads deployable by the nation they led.

Burson also examined the concept of beauty in our society. In one of the first composites made in 1982, she creatied composite portraits that were a comparison of styles between the 1950’s and the 1980’s, exploring how beauty is defined in our society. For example, her "First Beauty Composite" (1982) featured the faces of Bette Davis, Audrey Hepburn, Grace Kelly, Sophia Loren, and Marilyn Monroe. And her "Second Beauty Composite" (1982) featured images of Meryl Streep, Brooke Shields, Jane Fonda, Diane Keaton, and Jacqueline Bisset.

She also explored other themes through her composite portraits. Her "10 Businessmen From Goldman Sachs" (1982) was a blend of 10 businessmen from that firm, while her "First and Second Male Movie Star Composites" blended images of movie stars in yet another style comparison. The "Big Brother" image produced in 1983, was a mix of the faces of political figures Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, Mao, and Khomeini for a CBS TV special that recreated George Orwell’s Big Brother from his novel 1984.

The process of morphing faces was not only time-consuming but also required a considerable amount of skill and effort in its early days.

N.B.: “In 1982, the process that we used to morph faces was different in that we would overlay all the images on the eyes and ascertain an average. Then we would warp, or morph, each face to fit the average. It took 25 minutes to scan a face and morph it to the average face and then we’d combine them all together. It was an incredibly tedious process. Nowadays, there are some great programs available online which morph faces together and can weight them in different percentages as well.”

One of Nancy Burson’s most important works is the “Age Machine”, which utilized her patented technology of 1981, “The Method and Apparatus for Producing an Image of a Person’s Face at a Different Age.”

The “Age Machine” was an interactive installation that simulated the aging process, offering a glimpse into what viewers might look like in the future. The installation scanned the face, and the viewer interactively moved data points for their features (ends of eyes, nose, mouth etc.). Then the software applied an aging template that corresponded to the viewer’s facial structure. Over the years, David Kramlich increased the speed of the process from 25 minutes to just a few seconds making it possible for viewers to be active participants within the museum experience. Quickly garnering attention for its boundary-pushing creativity, the “Age Machine” used cutting-edge technology to delve into questions surrounding identity and aging. It was shown at many important venues including the Venice Biennale in 1995 and the New Museum (NYC) in 1992.

Another variation of the initial morphing process was used by law enforcement agencies to find missing children or adults, predicting how they would look many years after their disappearance. Copies of the software were acquired by the FBI, as well as the National Center for Missing Children. By the mid 80’s, at least half a dozen children and several adults were found from Burson’s updating methodologies and collaborations with law enforcement. Through her art, Burson did what other artists only dream about. She changed people's lives.

N.B.: “I was completely unaware of the software’s potential use in finding missing children. However, in 1983, the Ron Feldman Gallery asked me into a group exhibition called “The 1984 Show”. The piece I chose to exhibit were aged images of Prince Charles and Diana with their “composite” teenage son, William. A woman with a missing child saw the show and asked me if there was anything I could do to update children’s faces. It was the true beginning of my work with missing kids. I knew the process we had been using to composite faces needed to be adjusted to update children’s faces so David Kramlich and I reworked the process. At that point, there were some Hollywood producers who came to us with a couple of serious cases of parental abductions and when they were aired on national TV, the children were found within the hour. It was wild to see the images we’d created on a computer screen come to life when those kids were found.”

Based on the same technique, Burson developed other machines as well. The “Anomaly Machine” (1993) showed viewers how they would look with a facial anomaly based of the research and data that she collected in taking portraits of real children’s faces with various craniofacial disorders. The “Couples Machine” combined two people together in whatever percentages they wanted. All these machines were offshoots of the original Couples Machine from 1989, which combined viewers’ faces with movie stars and politicians and was shown originally at the Whitney Museum.

Later works (2000 - now)

Nancy Burson, DNA HAS NO COLOR (An a/p of the glass sculpture made at Berengo Studios in Morino and acquired by the Boca Raton Museum)

Besides the above creations, there was another important artwork that was based on Nancy’s development of "The Method and Apparatus for Producing an Image of a Person's Face at a Different Age". “The Human Race Machine” was a public art project which was inspired by a meeting in the mid-1998 with one of Zaha Hadid's staff and was launched at the Mind Zone in the London Millennium Dome on January 1st, 2000. It was the perfect backdrop for the project which was an immense success with long queues of visitors waiting for hours. “The Human Race Machine” used morphing technology to show people how they would look as a different race, including Asian, Black, Hispanic, Indian, Middle Eastern, and White. After the British launch, “The Human Race Machine” went on to be featured in diversity programs in colleges and universities across the US for over a decade. It was also featured in Burson’s traveling retrospective that began at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery in 2002, and was nominated for Best Museum Show of the Year by the American Art Critics Association.

The project provided viewers with the visual experience of being another race and perhaps helped to promote a message of unity by allowing people to experience what it’s like to be someone of a different race. Later she created several works that explore the concept of diversity and equality.

N.B.: “In 2000, I did a project for Creative Time that accompanied a group exhibition exploring DNA in which I showed the “Human Race Machine”. Accompanying the exhibition, Creative Time commissioned a billboard at Canel and Church Street that said, “There’s No Gene For Race.” I consider the “DNA HAS NO COLOR” message of these sculptures and billboard an update of that same concept. Race is merely a social construct having nothing to do with the science of genetics. In fact, our DNA is really transparent, although scientists color it so it can be seen. With the prevailing upturn in racism today, I believe “DNA HAS NO COLOR” is an even more timely message than “There’s No Gene For Race” was almost 23 years ago. We are all one race, the human one.”

Nancy Burson has always had a keen interest in political issues. In relationship to her “Human Race Machine”, she created a series of images of Donald Trump as different races prior to his election. The “What If He Were: Black-Asian-Hispanic-Middle Eastern-Indian” was originally commissioned by a prominent magazine, but the magazine decided not to publish the images. Despite this setback, Burson remained committed to her work. These images were her attempt to not only expose Trump as a racist, but to challenge public consciousness regarding racist beliefs in the US.

Even though the work depicting Trump could not be published in that magazine, Huffington Post eventually published it after it was shown at the Rose Gallery (Santa Monica, CA) in 2016.

Another work called “Trump/Putin” was selected for the cover of Time magazine in 2018. This work showcased a slow transformation of the faces of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin into one face. The image illustrated the sudden, unexpected liaison between thesse two leaders and the potential involvement by Russia in the 2016 election for the United States presidency.

Burson already knew the photo editor of Time magazine, Paul Moakley, who had selected one of her earlier works, “Androgyny” for Time’s book, “100 Photographs: The Most Influential Images of All Time”. Moakley was impressed by “Trump/Putin” and featured it on the cover of Time magazine. The image went viral immediately.

Nancy Burson's passion for addressing pressing political issues through art continues to this day, as evidenced by her recent work "The Face of Global Carbon Emissions". This piece depicts the top five heads of state whose countries are the biggest contributors to global warming. The composite image is weighted according to the approximate percentages of each country's carbon emissions. The featured leaders are Xi Jinping of China (contributing 28%), Joe Biden of the US (contributing 15%), Narendra Modi of India (contributing 7%), Vladimir Putin of Russia (contributing 5%), and Fumio Kishida of Japan (contributing 3%).

N.B.: “I prefer to make composites these days as political statements. “The Face of Global Carbon Emissions” grew out of my concern for our Mother Earth. We need to reduce our carbon emissions or risk extinction of humanity. I wanted to put a human face on the problem by combining the five world leaders who hold the power to change climate policies.”

Expressing social issues and bias

Nancy Burson has dedicated her career to exploring the complexities and mysteries of the human face and the societal issues it reflects. Faces have always been an important part of human communication and expression. Portraiture represents a person's likeness and has been used throughout history to depict individuals and their personalities, capturing their essence through subtle cues like facial expressions and body language. Nancy Burson does not use portraiture to represent personal expression. Rather, she highlights social, political, and cultural issues, focusing on larger societal biases and injustices.

The human face is a mysterious and changeable thing. Burson's art explores how it is influenced by social and scientific ideas and biases. Her work uncovers the fluidity of concepts such as beauty, sex, race, power, family, and even species. It challenges viewers to reevaluate their ways of seeing the world. She wants us to see the works and actively engage with them, instead of just decoratively viewing them.

Morphing Techniques and AI

Morphing techniques and many AI image generative programs blur the line between reality and illusion. AI can generate pictures and videos that appear almost real, and morphing techniques can allow for the seamless transition of one image into another. When these two technologies intersect, the possibilities for creating lifelike illusions are almost limitless.

One of the important AI examples of morphing techniques is the DeepFakes. It uses an AI algorithm to replace one person’s face with another realistic transformation. The technique raises deep concerns about the potential for creating fake news or propaganda.

Another example of the intersection of morphing techniques and AI is GAN (Generative Adversarial Networks). GAN is a type of deep learning model that can generate new realistic images by blending and morphing elements from other images. It is applied in various fields, like art, fashion, and design. In recent years, GANs have been used to create unique and visually striking art pieces that blend elements from different styles seamlessly. The resulting images are both surreal and captivating, blurring the line between reality and imagination.

Nancy Burson has been keeping a close eye on the advancements in technology, including the rise of artificial intelligence. While she acknowledges the potential benefits of this new tool, she also recognizes the potential for misuse and unintended consequences.

N.B.: “Each new technology brings its own potential misuses along with it. I consider AI to be a powerful new tool that I think is especially good at illustrating abstract concepts. Clearly some limitaitons have already been found, such as the software’s apparent racial bias that’s especially disturbing when used for law enforcement. I never imagined there would be a time that AI composited fake people would be used as spokespersons for websites. That’s terrifying to me.”

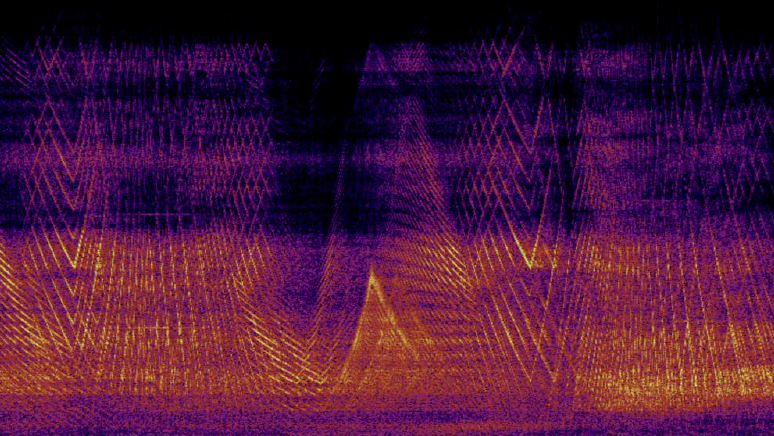

MANIFESTO TERRICOLA by SOLIMAN LOpEZ

We are thrilled to introduce the "Manifesto Terricola", an artistic and scientific project developed by Soliman Lopez in collaboration with Polo De Vinci, MIT Media Lab, ESAT, Viven Roussel, Maggie Coblentz, Javier Forment, and Lena Von Goedeke. The project explores the current state of humanity and our future, with a particular focus on the environmental changes happening on the planet. The manifesto is stored in DNA and preserved in a biodegradable ear-shaped sculpture on Svalbard Island in the Arctic. It defends a positivist view towards the use of biotechnology as new materials of human expression and working in harmony with nature. The message of the Manifesto Terricola is integrated into this time capsule, frozen and icy at the Arctic pole, as a kind of farewell to the Earth we once knew, to say that we have changed it and ourselves. The project draws inspiration from art history, using the format of a manifesto, and refers to Vincent Van Gogh's ear. Solimán López, a well-known figure in the contemporary art world, developed the project using his expertise in new technologies, new media art, blockchain, and biotechnology.

Written by Soliman Lopez

© S O L I M A N L O P E Z

1< INTRODUCTION

The main objective of this document is to explain the details related to the project "Manifesto Terricola" by artist and researcher Solimán López in collaboration with Polo De Vinci, MIT Media Lab and ESAT (Escuela Superior de Arte y Tecnnología). The project is developed under the supervision of researcher and expert of biomateriality, Viven Roussel with the support of researcher and artist Maggie Coblentz and the collaboration of bioinformatician Javier Forment and artist Lena Von Goedeke.

In the context of the residencies proposed by both institutions in collaboration and with the island of Svalbard as a field of work, the artist is selected to develop an artistic project relevant to the local, global, artistic and human context, which questions the current reality of humanity and our future, as well as introducing research opportunities within the framework of the analysis of the Arctic as a testimony of the environmental change present on planet Earth. That is why after several meetings and deliberations, taking into account the subject matter, the technological challenge and the proposed innovation, the working team has chosen the "Manifesto Terricola" project as the appropriate one based on the following details that are explained below in this document.

2< WHAT´S THE MANIFESTO TERRICOLA?

It is an artistic document that presents a state of the current situation of humanity in different areas such as economics, ethics and morality, psychology, geopolitics, the environment, art and the connection in between humans and the Earth.

But the document also contemplates a particular materiality, being stored in DNA and encapsulated in biodegradable bio printed material with the shape of an ear, produced to preserved on Svalbard Island in the Arctic.

Formally, it follows two historical approaches to the meaning of an artistic manifesto, being at the same time a work and text of intentions and a scientific tool. These intentions lie in an intrinsic analysis of materiality, the intangible, the anthropocene, science, digital storage and art itself.

The manifesto is separated into 5 conceptual blocks:

Block I: ENVIRONMENTAL TRANSITION.

Block II: SCIENCE AND BELIEFS Block

III: ECONOMICS Block

IV: TRANSHUMANISM / AUGMENTED HUMANS

Block V: CONSCIOUSNESS / ART

© S O L I M A N L O P E Z

Each of these content blocks is stored in its own DNA sequence and inserted all together in a bio print that saves and encapsulates the digital content.

The Manifesto claims pure conceptual production and the new materialities of the digital and intangible as a form of expression and a sublime relationship with nature in order to extend the understanding of the very essence of human technology and bioentities.

The Manifesto Terricola also defends a positivist stance towards the advances of biotechnology as new materials of human expression and conciliation with nature and the biological. The text proclaims the integration and acceptance of technology as a new engine of consciousness for the future of humanity, thought and art and positions our generation in context with a future one and vice versa. The overall message of the Manifesto Terricola is at the same time integrated into a natural time capsule, frozen and icy at the Arctic pole, as a kind of farewell to the once Earth to say, yes, we have changed you and at the same time we have changed ourselves.

The manifesto also calls for a conceptual engagement with the crucial debate of the moment, arguing that all current artwork must have an intrinsic critical eye on these issues in order to balance with the current moment.

The Manifesto takes the form of a sculpture in the shape of a bioprinted human ear containing the DNA-encoded information of the manifesto itself.

3< THE ARTISTIC WORK, ITS REPRESENTATION

The work consists of two parts. The content of the manifesto, its audio and image. The materiality that houses it, represented by a human ear printed three-dimensionally with what is called bioprinting.

This object has a strong representation in the history of art, having clear references. On the one hand, the tragic duel of the painter Vincent Van Gogh with his ear to "make himself heard", passing through the also famous one implanted in the forearm of the artist Stelarc to make an implant listen and at the same time speak, or the project of the also bio artist Joe Davis with the introduction in the DNA of a mouse ear of the image of the milky way.

These precedents serve as a solid base to create a new evolution of this ear concept that has listened to the history of art and that now proposes other materiality and adds concepts.

On the one hand it is an ear that represents in itself transhumanism by its own materiality and the possibility of imprinting itself with a bio material. On the other hand, this object/organ/listening interface holds frequencies information within itself and at the same time, like Stelarc's ear, listens and speaks and represents a global message like Joe Davis'. Of course, it also represents the tragedy of our humanity as destroyers of our own environment.

Within the project there is an important communication dimension linked to its distribution and dissemination. That is why certain actions and exhibitions are foreseen that will have as their main object a replica of the ice cane that incorporates the manifesto inside it.

The creation of large-format video projections and immersive installations are also foreseen.

4< MAIN PRECEPTS FOR THE MANIFESTO TERRICOLA

© S O L I M A N L O P E Z

¿- Why Terricola?

From the Latin terricola ("inhabitant of the earth or soil"). If we look at the etymology of the word, the prefix terri- is self-explanatory, earth coming from terra, but it is interesting to look at the suffix -cola, which comes from -cul referring to cultivation. On the other hand, the root -col/cul is related to the Indo- European root kwel which means to stir or to move and which we find for example in a word of Greek origin such as kyklos which means wheel. And it is even more interesting to say that the verb colere in Latin means to cultivate and to inhabit, which also has a connotation to the concept of sedentary, a term that we have already mentioned in relation to the first civilisations that manipulated cereals to make a viable economy in their environment and that is now called into question with the manifesto insofar as our land is no longer a land suitable for this cultivation or for this habitability, turning us into extra-terrestrial beings.

Why the Arctic and Svalbard?

The technical and conceptual characteristics to carry out the project are ideal in Svalbard. On the one hand, it is a sensitive place in the use of art as a model of communication and commitment to the preservation of the Arctic as a key place in the global balance. On the other hand, the scientific research intrinsic to the project finds in this latitude of the world, a perfect place to work in low temperature conditions, in an isolated place and with easy access for proper installation and monitoring. Finally, Svalbard has great symbolic power as a place weakened and victim of the repercussions of human activity and the accelerating impact of climate change, being a global icon of iconic significance for a committed and frontal message such as the one proposed here.

Who is the manifesto addressed to?

The target audience of this manifesto is anyone who wants to approach it in any of its forms, but within the framework of the general concept and the intellectual proposal it implies, we can identify 4 fundamental population groups in terms of the relationship they have with technology and the evolution of our species:

1º Humans who have assumed the change derived from the anthropocene and who, due to laziness, selfishness, ignorance, comfort and many other factors subjugated to the former, openly contribute to the uncontrolled entropy that generates the plausible imbalance we are experiencing.

2º Humans who intend with an outstanding use of technology to revert the changes to return the Earth to its ideal state of habitability, with advanced designs, sustainability as a fundamental word and cooperation.

© S O L I M A N L O P E Z

3º Humans who with an outstanding use of technology, like the first ones, are contributors to the growth of the anthropocene, but who have in their roadmap the exploration of other places in space that leave behind the Earth as habitat in a sort of space colonisation based on the exponential growth of our technology, consciousness, energy and species.

4º Humans isolated from the debate with basic primary needs derived from their level of consciousness, resources, geographic location and politics causing a lack of capacity to position themselves on the issue.

Motivations:

Every work of art, whatever its nature, requires an action, however symbolic it may be. A motivation. I define below some of the motivations for the creation of the Manifesto Terricola.

Eco anxiety: It has been mentioned before, but this manifesto captures the global eco-anxieties derived from a society in biological check.

Art: It is in itself a motivation, but an instrument and vehicle of communication. A means of visual, conceptual and graphic transmission. Symbol and information package, as well as a generator of community and debate.

Message:

It is said that the end is the message and in this case this issue is very evident. The proposed message is a message that is embedded in neutrality. The manifesto proposes a place of debate and a message towards a potential recipient of the future to make them understand the moment they are in when they receive it and to draw clear lines of understanding and experience around the main issue of the project: the "habitability of the earth and our suitability to it".

Permafrost: Leaving a message for generations to come has always been in the view of all our civilisations. From the most ancestral ones in their eagerness to build in stone and leave us hidden messages in every centimetre. This intention is also present in this project through the staging of the manifesto through a natural process provoked under the concept of Permafrost.

Research: To pose a scientific experiment that can re-signify the sustainable encounter of humanity's information in balance with nature or what we could call biodata storage.

5< SCIENTIFIC DIMENSION

© S O L I M A N L O P E Z

Numerous scientific studies have already identified DNA as a suitable materiality as a bio-marker for the study of different characteristics related to melting ice, permafrost, movement, friction and the identification of life in glacial environments and in general in hydrological environments in which traces are particularly complicated to control. It is interesting to highlight the study published in Environmental Science & Technology where problems are solved with the use of PLA (Polylactic Acid), and encapsulants for DNA such as silica or clay gel among others, which in conjunction make these bio-markers a perfect material.

In our eagerness to keep the environment intact and not generate any alteration in the short or long term, we have chosen the same materiality for our artistic action, knowing that it is a material that is already being used in different ongoing studies in places such as Antarctica, Latin America and Asia.

Earlier we explained how the manifesto is an enunciative text and at the same time a work in itself. But it is also a scientific object that helps us to recognise the changes in the place in which it is embedded, identifying four fundamental lines of scientific contribution in the context of current research on the island.

- DNA as a guarantor of digital information: We are interested in studying the way in which the DNA that contains the information in the manifest, remains in extreme conditions of temperature, friction and radiation. We intend for the manifest to become a proof-of-life beacon that will be recovered in the coming years and provide us with hard evidence of the versatility of this digital information storage model that can help store part of our general culture.

We can demonstrate that the information integrated in the glacier through the manifest is durable and a future opportunity that revalues the ecosystem and connects it with new nanotechnologies.

- Biomaterial as a guarantor of environmental neutrality: We also want to demonstrate with this action how scientific and artistic production can be carried out with 0 environmental impact through the choice of suitable materials that arise from in-depth research in biotechnology material.

- Analysis of the suitability of storing digital information in a way that is harmless and sustainable for nature and sensitive ecosystems: Demonstration of new environmental applications for the linking and storage possibilities of the visual and digital culture of today's society. Stable natural media as an inert repository.

- DNA as a vibratory witness: Analysis of the vibrational changes in DNA resulting from climate change and environmental disturbances.

Our project is an exploration of data conservation and new materialities. We are interested in studying how the synthetic DNA, which contains a translated digital information in, can hold up under extreme conditions of temperature, friction and radiation. This takes the form of an Art-Science project lead by the Université Léonard de Vinci (represented by Association Léonard de Vinci) and the artist Soliman Lopez. The artist proposes to explore the question of the narratives of humanity at a time of climate crisis and dematerialisation of data with a DNA encapsulation in biodegradable biomaterial - biotechnology developed by the Tissue Labs and DNA method encoding with the bioinformatic Javier Forment form Universidad Politécnica de Valencia and the Genscript laboratory which it the artist is collaborating since 4 years. The Manifesto Terricola claims pure conceptual production and the new materialities of the digital and intangible as a form of expression and a sublime relationship with nature in order to extend the understanding of the essence of human technology and nature.